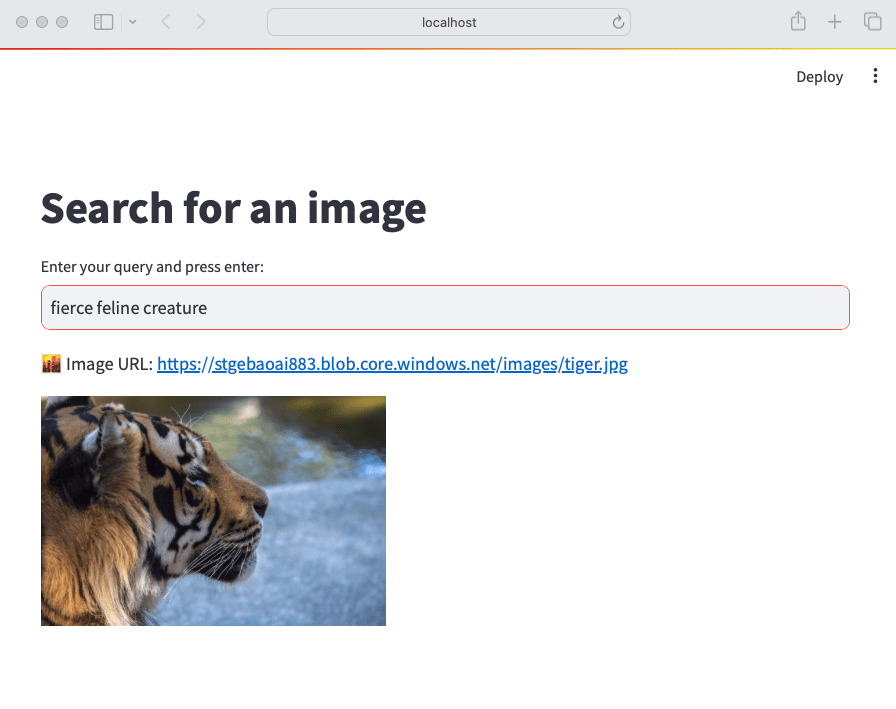

Whenever we build applications on top of LLMs such as OpenAI’s gpt-4o, we often use the RAG pattern. RAG stands for retrieval augmented generation. You use it to let the LLM answer questions about data it has never seen. To answer the question, you retrieve relevant information and hand it over to the LLM to generate the answer.

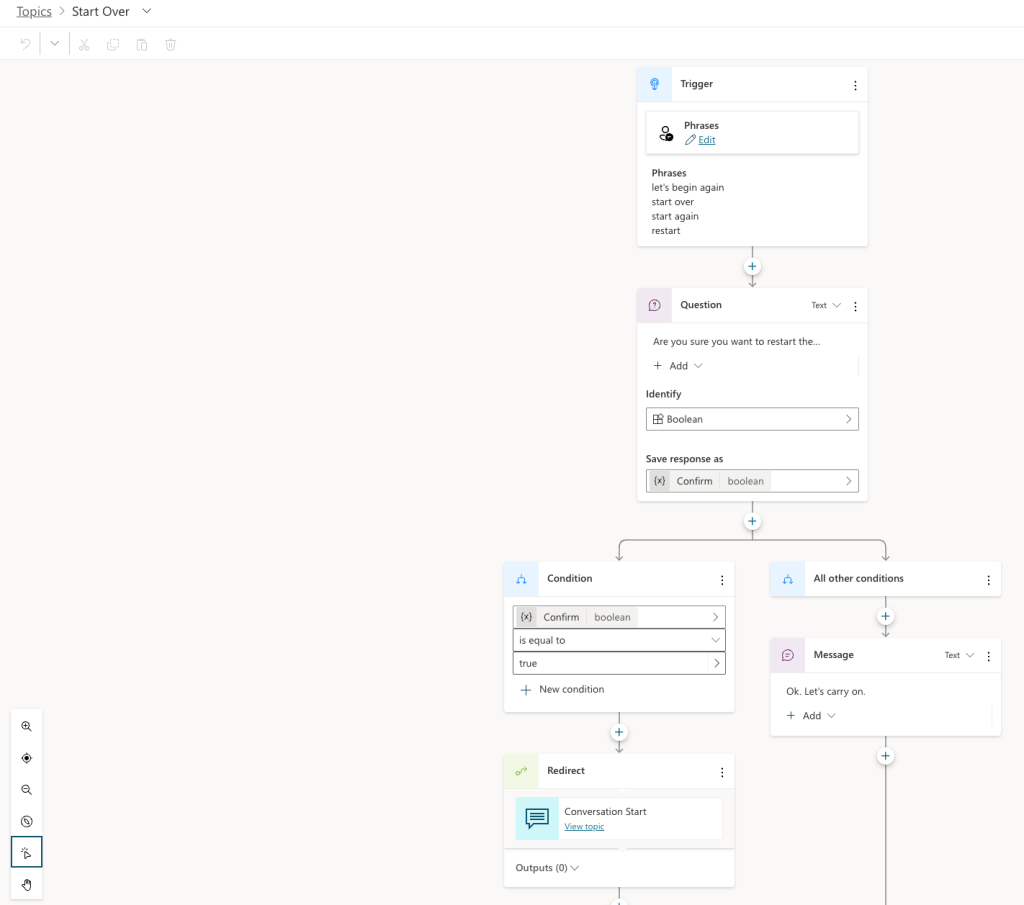

The diagram below illustrates both the data ingestion and querying part from a high level, using gtp-4 and a vector database in Azure, Azure AI Search.

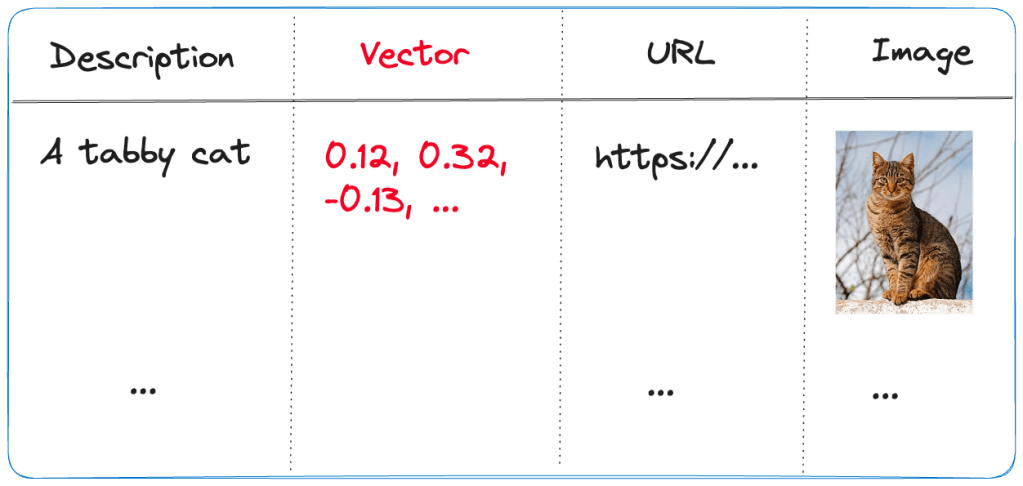

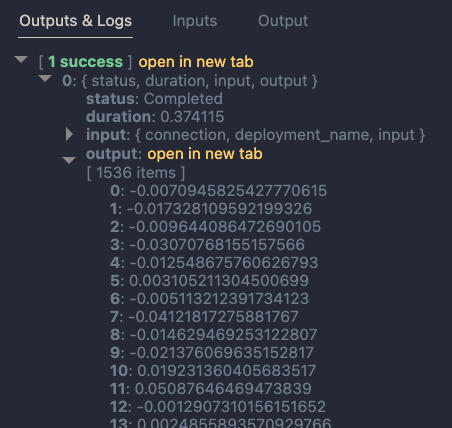

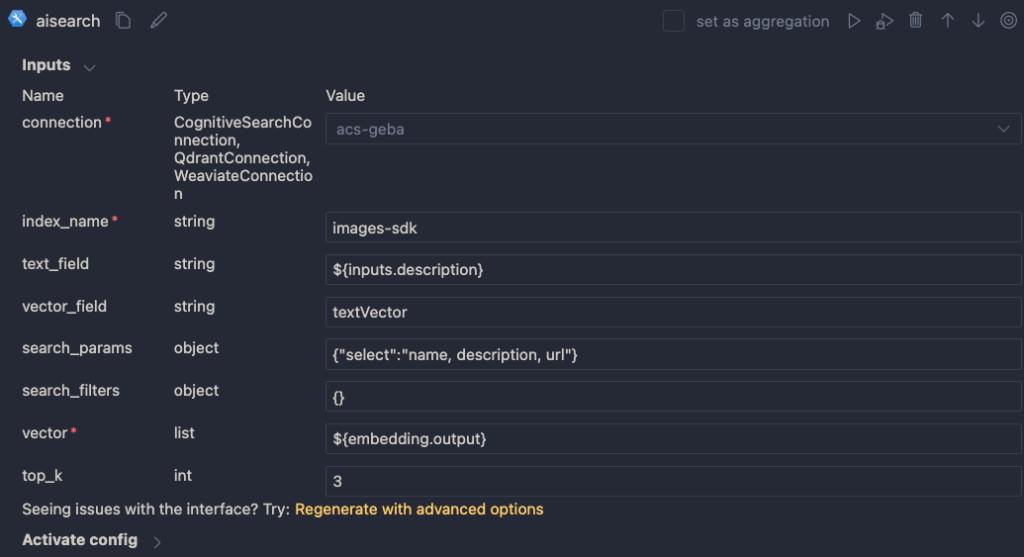

Above, our documents are chunked and vectorized. These vectors are stored in Azure AI Search. Vectors allow us to find text chunks that are similar to the query of the user. When a user types a question, we vectorize the question, find similar vectors and hand the top n matches to the LLM. The text chunks that are found are put in the prompt together with the original question. Check out this page to learn more about vectors.

Note that above is the basic scenario in its simplest form. You can optimize this process in several ways, both in the indexing and the retrieval phase. Check out the RAG From Scratch series on YouTube to learn more about this.

Limitations of baseline RAG

Although you can get far with baseline RAG, it is not very good at answering global questions about an entire dataset. If you ask “What are the main themes in the dataset?” it will be hard to find text chunks that are relevant to the question unless you have the main themes described in the dataset itself. Essentially, this is a query-focused summarization task versus an explicit retrieval task.

In the paper,

From Local to Global: A Graph RAG Approach to Query-Focused Summarization, Microsoft proposes a solution that is based on knowledge graphs and intermediate community summaries to answer these global questions more effectively.

If it is somewhat unclear what the difference between baseline RAG and Graph RAG looks like, watch this video on YouTube where it is explained in more detail:

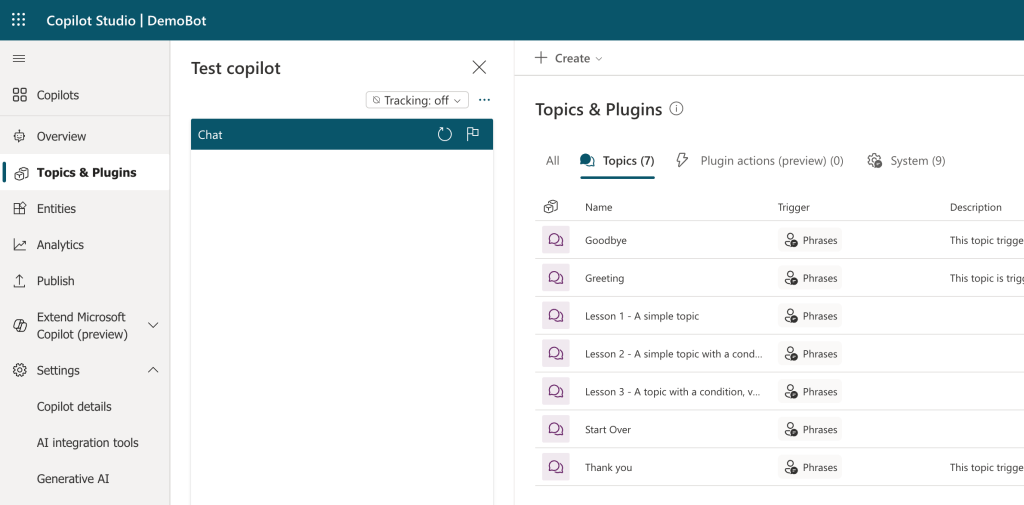

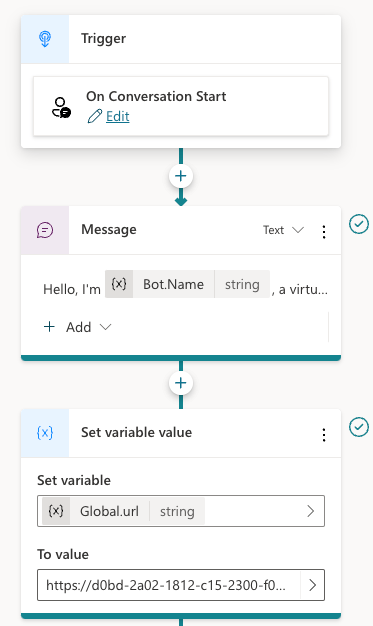

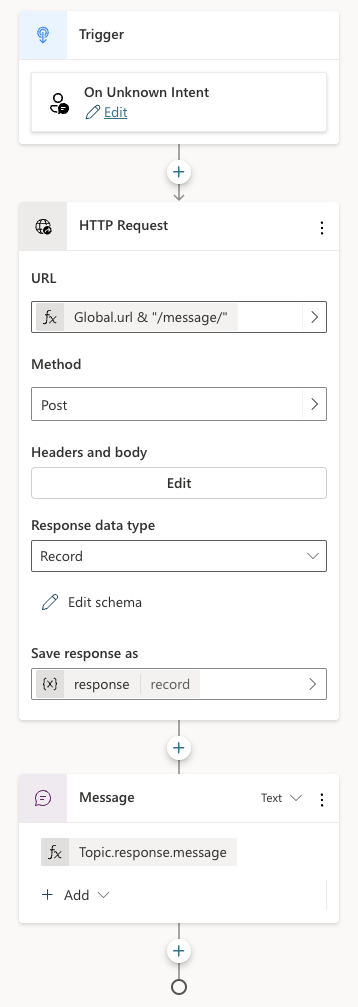

Getting started by creating an index

Microsoft has an open source, Python-based implementation of Graph RAG for both local and global queries. We’ll discuss local queries a bit later in this post and focus on global for now. Check out the GitHub repo for more information.

If you have Python on your local machine, it is easy to try it out:

- Make a folder and create a Python virtual environment in it

- Make sure the Python environment is active and run

pip install graphrag - In the folder, create a folder called

inputand put some text files in it with your content - From the folder that contains the input folder, run the following command:

python -m graphrag.index --init --root . - This creates a

.envfile and asettings.yamlfile. - In the

.envfile, enter your OpenAI key. This can also be an Azure OpenAI key. Azure OpenAI requires additional settings in thesettings.yamlfile:api_base,api_version,deployment_name. - I used OpenAI directly and modified the model in

settings.yaml. Find themodelsetting and set it togpt-4o.

You are now ready to run the indexing pipeline. Before running it, know that this will do a lot of LLM calls depending on the data you put in the index folder. In my tests, with 800KB of text data, indexing cost between 10 and 15 euros. Here’s the command:

python -m graphrag.index --root .

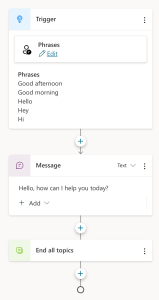

To illustrate what happens, take a look at the diagram below:

Above, let’s look at it from top to bottom, excluding the user query section for now:

- Source documents in the input folder are split into pieces of 300 tokens with 100 tokens overlap. Microsoft uses the

cl100k_basetokenizer which is the one used by gpt-4 and not gpt-4o. That should not have an impact. You can adjust the token size and overlap. With a larger token size, less LLM calls are made in subsequent steps but element extraction might be less precise. - With the help of gpt-4o, elements are extracted from each chunk. These elements are the entities and relationships between entities in the graph that is being built. In addition, claims about the entities are extracted. The paper and diagram above uses the term covariates. This is a costly operation if you have a lot of data in the input folder.

- Text descriptions of the elements are generated.

After these steps, a graph is built that contains all the entities, relationships, claims and element descriptions that gpt-4o could find. But the process does not stop there. To support global queries, the following happens:

- Detection of communities inside the graph. Communities are groups of closely related entities. They are detected using the Leiden algorithm. In my small dataset, about 250 communities were detected.

- Per community, community summaries are created with gpt-4o and stored. These summaries can later be used in global queries.

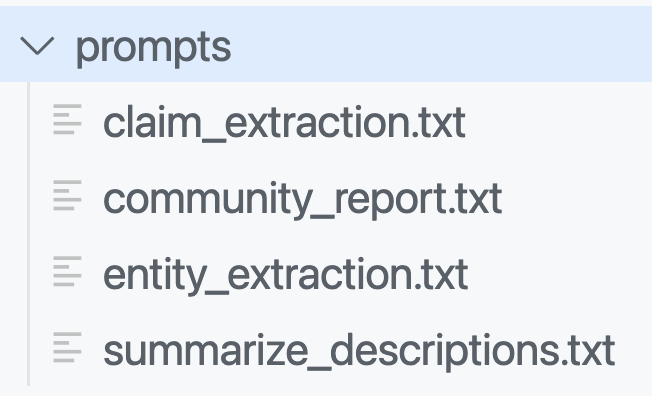

To make all of the above work, a lot of LLM calls have to be made. The prompts that are used can be seen in the prompts folder:

You can and probably should modify these prompts to match the domain of your documents. The entity extraction prompt contains examples to teach the LLM about the entities it should extract. By default, entities such as people, places, organizations, etc.. are detected. But if you work with building projects, buildings, bridges, construction materials, the prompt should be adjusted accordingly. The quality of the answers will depend greatly on those adjustments.

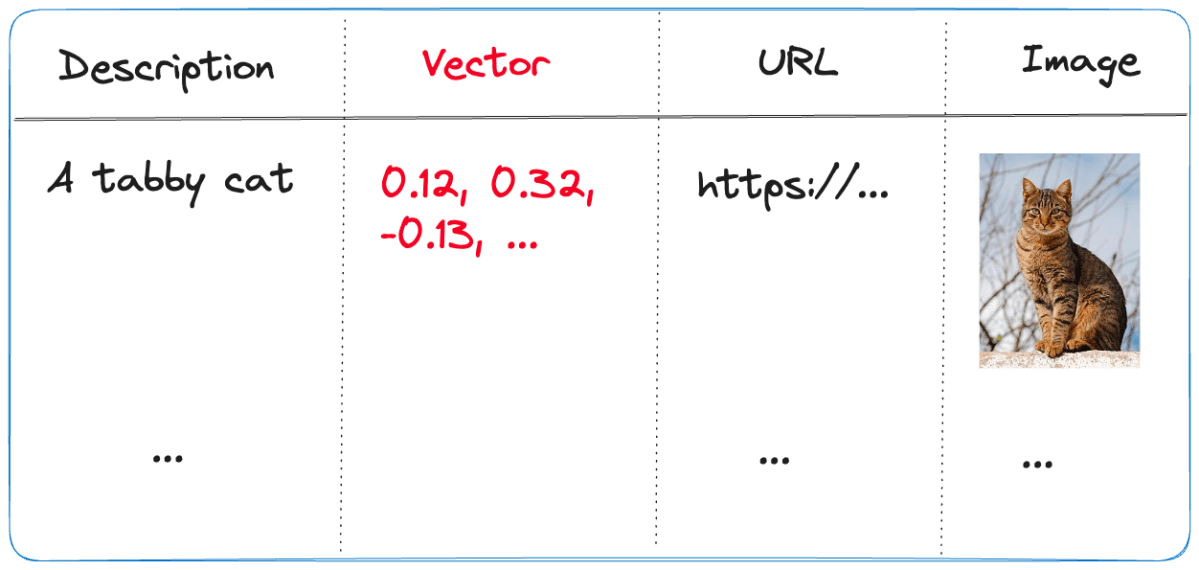

In addition to the graph, the solution uses the open source LanceDB to store embeddings for each text chuck. There is only one table in the database with four fields:

- id: unique id for the chunk

- text: the text in the chunk

- vector: the vector of the chunk; by default the

text-embedding-3-smallmodel is used - attributes: e.g., {“title”: “\”title here\””}

The graph and related data is stored in parquet files in an artifacts folder inside another folder with a timestamp. For example:

If you have a parquet viewer, you can check the create_final_entities.parquet file to check the detected entities. You will find entity types like ORGANIZATION, PERSON, GEO, EVENT, CONCEPT, etc… Every entity has a description and links back to the text unit ids. The text units are the chunks.

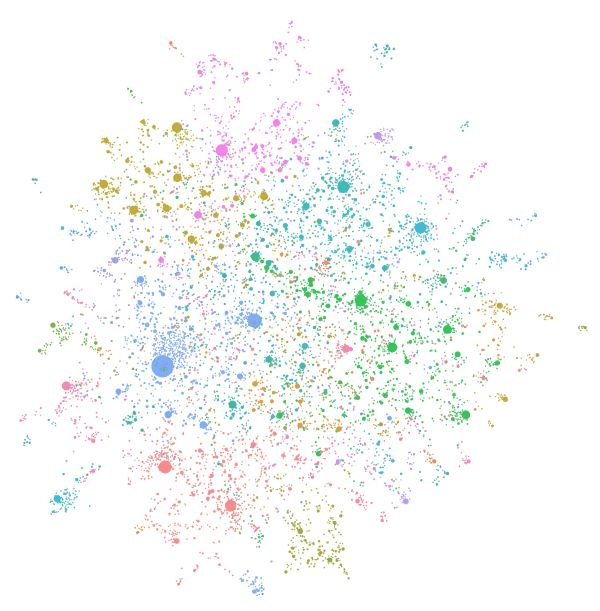

Note that, if you want the graph in GraphML format, set snapshots.graphml to true in settings.yaml. Your artifacts folder will then contain .graphml files. You can load those in a viewer like Gephi:

If you already ran the indexer without setting this value, you can just run it again. Graph RAG has a caching layer so you will not incur costs when you run the indexer again simply to generate the .graphml files.

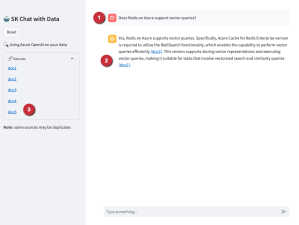

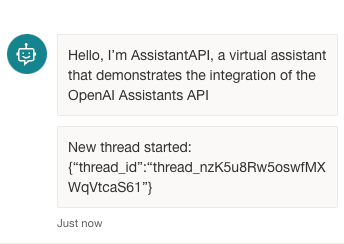

Global Search

Now let’s do a global query. A global query uses the generated community summaries to answer the question. The intermediate answers are used to generate the final answer.

A global query is not just one LLM call but several ones. The total token cost is relatively high compared to a typical similarity search that uses between 3 to 5 retrieved chunks. It’s not uncommon to see >10 LLM calls with 200K token. You can control the token usage in settings.yaml. See the global_search settings at the bottom.

To do a global query, run the command below. I have the book 1984 in the corpus so let’s ask for the main themes:

python -m graphrag.query \

--root . \

--method global \

"What are the top themes in 1984?"Note that an LLM can answer this on its own since it knows about 1984. That’s not the point here. The answer you get will come from the index:

### Top Themes in *1984*

**1. Totalitarianism and Absolute Control**

The Party in Oceania exercises absolute control over its citizens, manipulating historical records, maintaining a state of perpetual conflict, and enforcing oppressive policies through purges, arrests, tortures, imprisonments, and vaporizations [Data: Reports (211)]. The regime's control extends to every aspect of life, including personal relationships, sexual behavior, and even thoughts, enforced by the Thought Police and the omnipresent Telescreen [Data: Reports (141, 183, 223, 185, 191, 181, 151, 116, 186)].

**2. Surveillance and Psychological Manipulation**

Surveillance is a pervasive theme, with the Telescreen and the Thought Police constantly monitoring individuals to ensure compliance and suppress dissent [Data: Reports (52, 141, 183, 223, 185, 191, 181, 151, 116, 186)]. The Party uses psychological manipulation techniques such as doublethink, Newspeak, and the alteration of historical records to control and limit the range of thought among its citizens [Data: Reports (141, 175, 183, 181, 215, 149, 179, 177, 178, 165, 58)].

**3. Manipulation of Truth and Reality**

The Party manipulates historical records and information to maintain its narrative and control over reality. This is evident in Winston's work at the Ministry of Truth and the concept of doublethink, which allows individuals to accept two contradictory beliefs simultaneously [Data: Reports (141, 175, 183, 181, 215, 149, 179, 177, 178, 165, 58)]. The Memory Hole is used to destroy documents, ensuring that information is permanently erased, highlighting the Party's control over historical narratives [Data: Reports (52)].

**4. Continuous Warfare**

Oceania is engaged in a perpetual state of war with Eastasia and Eurasia. This continuous warfare serves to maintain the Party's control over the population and justify its oppressive policies [Data: Reports (211, 178, 214)]. The war consumes surplus goods, maintains a hierarchical structure, and impacts the mental states of individuals, ensuring that the populace remains divided and distracted [Data: Reports (211, 178, 214, 208)].

**5. Rebellion and Resistance**

Despite the oppressive regime, themes of rebellion and resistance are present, as seen through characters like Winston and Julia. Winston's clandestine activities, such as his relationship with Julia and his hope in the Proles, reflect his desire to rebel against the Party's oppressive regime [Data: Reports (141, 183, 151, 182, 101, 186)]. The Brotherhood represents an underground network aiming to overthrow the state of Oceania, highlighting the existence of resistance within the oppressive regime [Data: Reports (211, 64, 152)].

**6. Class Struggle and Social Hierarchy**

The distinction between the Inner Party, Outer Party, and Proles highlights the rigid social hierarchy within Oceania. The Party's control over the Proles and the limited privileges of the Outer Party members emphasize the theme of class struggle [Data: Reports (141, 66, 185, 211, 182, 124)]. The Proles, despite their subjugation, are seen as a potential source of hope and rebellion [Data: Reports (182, 64)].

**7. Language as a Tool of Control**

Newspeak, a language created by The Party, is designed to limit the range of thought and eliminate any possibility of rebellious thoughts. By controlling language, The Party effectively controls thought, making it impossible for individuals to conceptualize or express subversive ideas [Data: Reports (177, 179, 181, 149, 114)].

**8. Fear and Psychological Torture**

The Party uses fear and psychological torture to maintain control, exemplified by the use of Room 101, where individuals are subjected to their worst fears. Winston's torture with the cage containing rats demonstrates the regime's ability to break individuals' spirits [Data: Reports (169, 145, 224, 220)].

These themes collectively illustrate the oppressive nature of the regime in *1984* and its impact on personal freedom, truth, and reality. The Party's extensive use of surveillance, psychological manipulation, and control over information ensures its dominance and the suppression of any potential dissent.Local Search

A local search generates answers by combining data from the knowledge-graph with text chunks of the raw documents. This method is suitable for questions that require an understanding of specific entities mentioned in the documents (e.g. Who does Winston interact with?). The following notebook contains more information about a local search with Python: https://github.com/microsoft/graphrag/blob/a22003c302bf4ffeefec76a09533acaf114ae7bb/examples_notebooks/local_search.ipynb#L43

To do a local search from the CLI, use the following command:

python -m graphrag.query \

--root . \

--method local \

"Who is Winston? Who does he interact with and why?"A local search uses similarity search to find entities in the graph as entry points. Once these entry points are found, the graph is used to find further entities of interest. A local search requires the LanceDB embeddings store while a global search does not.

The response to the above question:

### Who is Winston?

Winston is a complex character from George Orwell's novel "Nineteen Eighty-Four." He is a member of the Outer Party and works at the Ministry of Truth, where his job involves altering historical records to fit the Party's propaganda. Winston is deeply resentful of the Party and Big Brother, harboring a sense of intellectual inferiority and mental domination by figures like O'Brien. His life is marked by intense fear, paranoia, and physical and emotional suffering, particularly during his interactions with O'Brien, who tortures and interrogates him [Data: Entities (8, 3)].

Winston's reflections on reality, power, and the nature of suffering are central to his character. He contemplates the symbolic meaning of chess, the principles of Ingsoc, and the dominion of The Party. His dreams and memories, including the tragic death of his mother and sister, the bells of St. Clement's, and his early childhood, provide a poignant backdrop to his internal struggles [Data: Entities (8)].

### Interactions and Relationships

#### Julia

Winston's most significant relationship is with Julia, a fellow Party member. Despite the risks, they engage in a love affair, renting a room from Mr. Charrington for their secret meetings. Julia represents a source of intimacy and rebellion for Winston, as they navigate their dangerous liaison under the watchful eyes of The Party [Data: Entities (8)].

#### O'Brien

O'Brien is another crucial figure in Winston's life. Initially, Winston feels a sense of connection and admiration towards O'Brien, hoping that his political orthodoxy is not perfect. However, O'Brien ultimately becomes his torturer, subjecting Winston to severe psychological and physical pain. Despite this, Winston experiences moments of connection and even a peculiar intimacy with O'Brien [Data: Entities (8)].

#### Mr. Charrington

Mr. Charrington is the shop owner who rents a room to Winston and Julia for their secret meetings. Initially, he appears discreet and non-judgmental, but later reveals a more authoritative and alert persona, indicating his role in the Party's surveillance [Data: Entities (317)].

#### Other Characters

Winston also interacts with various other characters, such as Syme, Parsons, and the old man in the pub. These interactions reveal his curiosity about the past and the changes brought about by The Party. For instance, Syme is a colleague who discusses the principles of Newspeak with Winston, while Parsons is a fellow employee at the Ministry of Truth [Data: Entities (8, 83)].

### Conclusion

Winston is a deeply reflective and observant character, constantly grappling with the oppressive nature of The Party and his own internal conflicts. His interactions with Julia, O'Brien, Mr. Charrington, and others provide a multifaceted view of his struggles and the dystopian world he inhabits. Through these relationships, Winston's character is fleshed out, revealing the complexities of life under totalitarian rule.Note that the output contains references to entities that were found. For example, the section about Mr. Charrington specifies entity 317. In the Gephi Data Laboratory, we can easily find that entity using the human_readable_id:

When you are building an application, the UI could provide links to the entities for further inspection.

Conclusion

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has emerged as a powerful technique for enhancing language models’ ability to answer questions about specific datasets. While baseline RAG excels at answering specific queries by retrieving relevant text chunks, it struggles with global questions that require a comprehensive understanding of the entire dataset. To address this limitation, Microsoft has introduced Graph RAG, an innovative approach that leverages knowledge graphs and community summaries to provide more effective answers to global queries.

Graph RAG’s indexing process involves chunking documents, extracting entities and relationships, building a graph structure, and generating community summaries. This approach allows for more nuanced and context-aware responses to both local and global queries. While Graph RAG offers significant advantages in handling complex, dataset-wide questions, it’s important to note that it comes with higher computational costs and requires careful prompt engineering to achieve optimal results. As the field of AI continues to evolve, techniques like Graph RAG represent an important step towards more comprehensive and insightful information retrieval and generation systems.