In this post, I want to talk about the Python backend I built for an AG-UI demo project. It is part of a larger project that also includes a frontend that uses CopilotKit:

This post discusses the Python AG-UI server that is built with Microsoft Agent Framework.

All code is on GitHub: https://github.com/gbaeke/agui. Most of the code for this demo was written with GitHub Copilot with the help of Microsoft Docs MCP and Context7. 🤷

What is AG-UI?

Before we dive into the code, let’s talk about AG-UI. AG-UI is a standardized protocol for building AI agent interfaces. Think of it as a common language that lets your frontend talk to any backend agent that supports it, no matter what technology you use.

The protocol gives you some nice features out of the box:

- Remote Agent Hosting: deploy your agents as web services (e.g. FastAPI)

- Real-time Streaming: stream responses using Server-Sent Events (SSE)

- Standardized Communication: consistent message format for reliable interactions (e.g. tool started, tool arguments, tool end, …)

- Thread Management: keep conversation context across multiple requests

Why does this matter? Well, without a standard like AG-UI, every frontend needs custom code to talk to different backends. With AG-UI, you build your frontend once and it works with any AG-UI compatible backend. The same goes for backends – build it once and any AG-UI client can use it.

Under the hood, AG-UI uses simple HTTP POST requests for sending messages and Server-Sent Events (SSE) for streaming responses back. It’s not complicated, but it’s standardized. And that’s the point.

AG-UI has many more features than the ones discussed in this post. Check https://docs.ag-ui.com/introduction for the full picture.

Microsoft Agent Framework

Now, you could implement AG-UI from scratch but that’s a lot of work. This is where Microsoft Agent Framework comes in. It’s a Python (and C#) framework that makes building AI agents really easy.

The framework handles the heavy lifting when it comes to agent building:

- Managing chat with LLMs like Azure OpenAI

- Function calling (tools)

- Streaming responses

- Multi-turn conversations

- And a lot more

The key concept is the ChatAgent. You give it:

- A chat client (like Azure OpenAI)

- Instructions (the system prompt)

- Tools (functions the agent can call)

And you’re done. The agent knows how to talk to the LLM, when to call tools, and how to stream responses back.

What’s nice about Agent Framework is that it integrates with AG-UI out of the box, similar to other frameworks like LangGraph, Google ADK and others. You write your agent code and expose it via AG-UI with basically one line of code. The framework translates everything automatically – your agent’s responses become AG-UI events, tool calls get streamed correctly, etc…

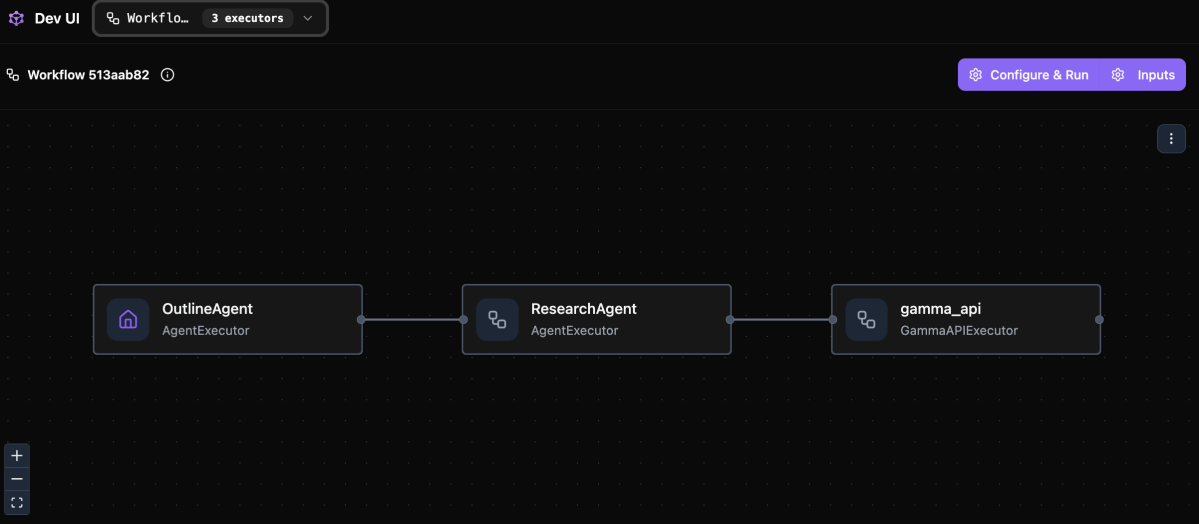

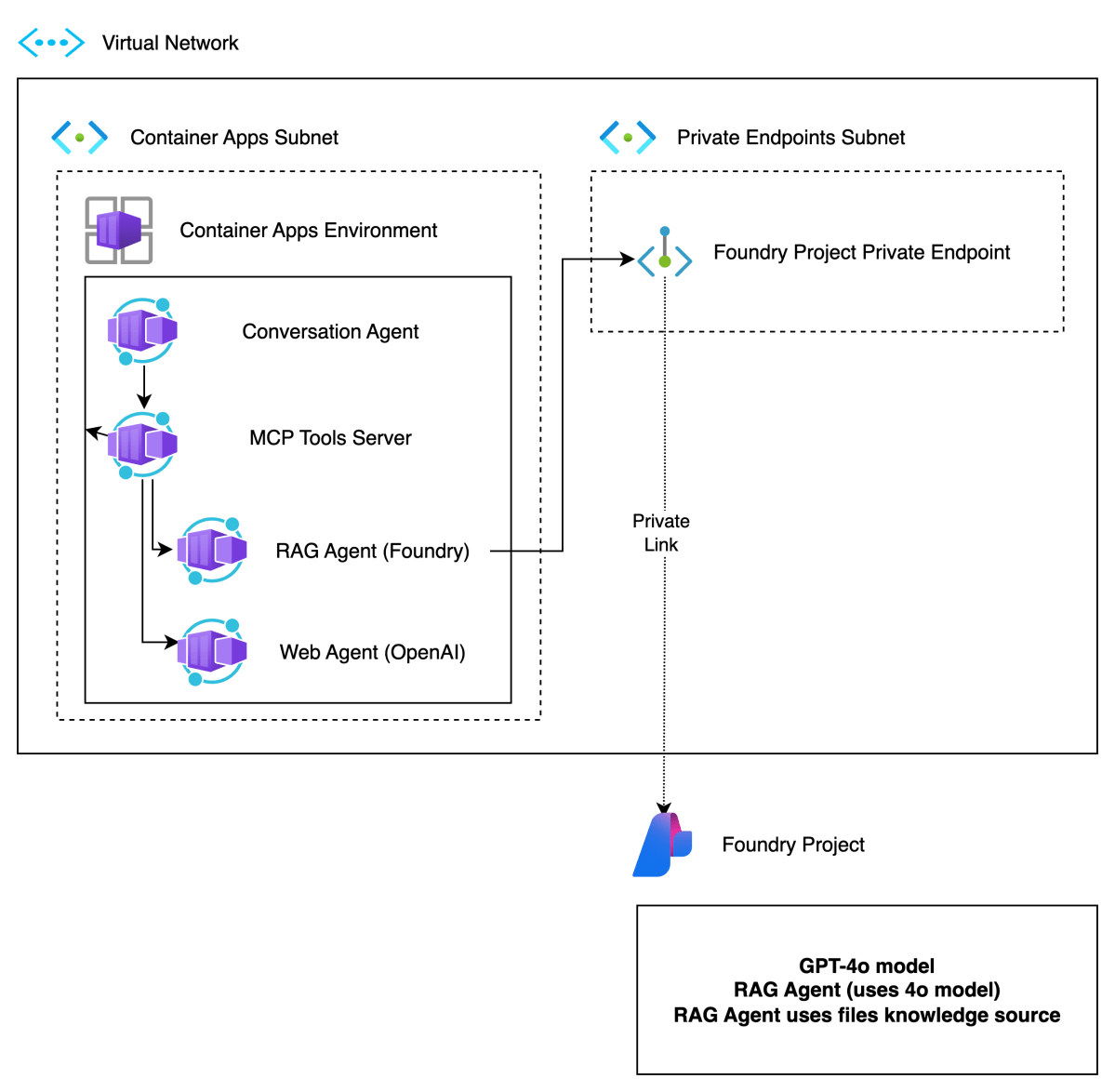

The integration with Microsoft Agent Framework was announced on the blog of CopilotKit, the team behind AG-UI. The blog included the diagram below to illustrate the capabilities:

The Code

Let’s look at how this actually works in practice. The code is pretty simple. Most of the code is Microsoft Agent Framework code. AG-UI gets exposed with one line of code.

The Server (server.py)

The main server file is really short:

import uvicorn

from api import app

from config import SERVER_HOST, SERVER_PORT

def main():

print(f"🚀 Starting AG-UI server at http://{SERVER_HOST}:{SERVER_PORT}")

uvicorn.run(app, host=SERVER_HOST, port=SERVER_PORT)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

That’s it. We run a FastAPI server on port 8888. The interesting part is in api/app.py:

from fastapi import FastAPI

from agent_framework.ag_ui.fastapi import add_agent_framework_fastapi_endpoint

from agents.main_agent import agent

app = FastAPI(title="AG-UI Demo Server")

# This single line exposes your agent via AG-UI protocol

add_agent_framework_fastapi_endpoint(app, agent, "/")

See that add_agent_framework_fastapi_endpoint() call? That’s all you need. This function from Agent Framework takes your agent and exposes it as an AG-UI endpoint. It handles HTTP requests, SSE streaming, protocol translation – everything.

You just pass in your FastAPI app, your agent, and the route path. Done.

The Main Agent (agents/main_agent.py)

Here’s where we define the actual agent with standard Microsoft Agent Framework abstractions:

from agent_framework import ChatAgent

from agent_framework.azure import AzureOpenAIChatClient

from azure.identity import DefaultAzureCredential

from config import AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT, AZURE_OPENAI_DEPLOYMENT_NAME

from tools import get_weather, get_current_time, calculate, bedtime_story_tool

# Create Azure OpenAI chat client

chat_client = AzureOpenAIChatClient(

credential=DefaultAzureCredential(),

endpoint=AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT,

deployment_name=AZURE_OPENAI_DEPLOYMENT_NAME,

)

# Create the AI agent with tools

agent = ChatAgent(

name="AGUIAssistant",

instructions="You are a helpful assistant with access to tools...",

chat_client=chat_client,

tools=[get_weather, get_current_time, calculate, bedtime_story_tool],

)

This is the heart of the backend. We create a ChatAgent with:

- A name: “AGUIAssistant”

- Instructions: the system prompt that tells the agent how to behave

- A chat client:

AzureOpenAIChatClientthat handles communication with Azure OpenAI - Tools: a list of functions the agent can call

The code implements a few toy tools and a sub-agent to illustrate how AG-UI handels tool calls. The tools are discussed below:

The Tools (tools/)

In Agent Framework, tools can be Python functions with a decorator:

from agent_framework import ai_function

import httpx

import json

@ai_function(description="Get the current weather for a location")

def get_weather(location: str) -> str:

"""Get real weather information for a location using Open-Meteo API."""

# Step 1: Geocode the location

geocode_url = "https://geocoding-api.open-meteo.com/v1/search"

# ... make HTTP request ...

# Step 2: Get weather data

weather_url = "https://api.open-meteo.com/v1/forecast"

# ... make HTTP request ...

# Return JSON string

return json.dumps({

"location": resolved_name,

"temperature": current["temperature_2m"],

"condition": condition,

# ...

})

The @ai_function decorator tells Agent Framework “this is a tool the LLM can use”. The framework automatically:

- Generates a schema from the function signature

- Makes it available to the LLM

- Handles calling the function when needed

- Passes the result back to the LLM

You just write normal Python code. The function takes typed parameters (location: str) and returns a string. Agent Framework does the rest.

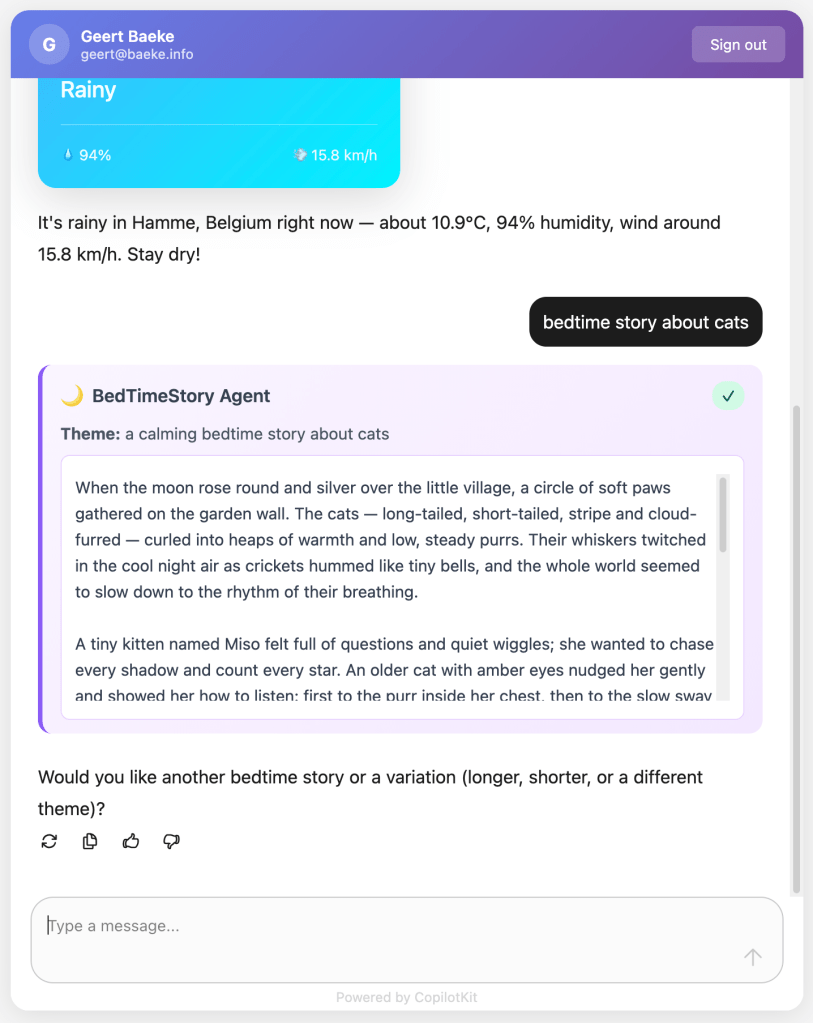

The weather tool calls the Open-Meteo API to get real weather data. In an AG-UI compatible client, you can intercept the tool result and visualize it any way you want before the LLM generates an answer from the tool result:

Above, when the user asks for weather information, AG-UI events inform the client that a tool call has started and ended. It also streams the tool result back to the client which uses a custom component to render the information. This happens before the chat client generates the answer based on the tool result.

The Subagent (tools/storyteller.py)

This is where it gets interesting. In Agent Framework, a ChatAgent can become a tool with .as_tool():

from agent_framework import ChatAgent

from agent_framework.azure import AzureOpenAIChatClient

# Create a specialized agent for bedtime stories

bedtime_story_agent = ChatAgent(

name="BedTimeStoryTeller",

description="A creative storyteller that writes engaging bedtime stories",

instructions="""You are a gentle and creative bedtime story teller.

When given a topic, create a short, soothing bedtime story for children.

Your stories should be 3-5 paragraphs long, calming, and end peacefully.""",

chat_client=chat_client,

)

# Convert the agent to a tool

bedtime_story_tool = bedtime_story_agent.as_tool(

name="tell_bedtime_story",

description="Generate a calming bedtime story based on a theme",

arg_name="theme",

arg_description="The theme for the story (e.g., 'a brave rabbit')",

)

This creates a subagent – another ChatAgent with different instructions. When the main agent needs to tell a bedtime story, it calls tell_bedtime_story which delegates to the subagent.

Why is this useful? Because you can give each agent specialized instructions. The main agent handles general questions and decides which tool to use. The storyteller agent focuses only on creating good stories. Clean separation of concerns.

The subagent has its own chat client and can have its own tools too if you want. It’s a full agent, just exposed as a tool.

And because it is a tool, you can render it with the standard AG-UI tool events:

Testing with a client

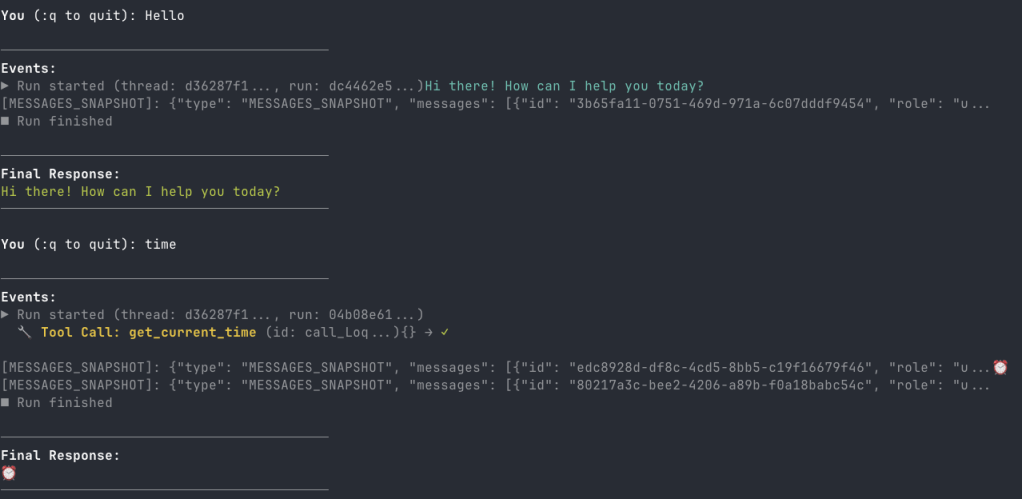

In src/backend there is a Python client client_raw.py. When you run that client against the server and invoke a tool, you will see something like below:

This client simply uses httpx to talk the AG-UI server and inspects and renders the AG-UI events as they come in.

Why This Works

Let me tell you what I like about this setup:

Separation of concerns: The frontend doesn’t know about Python, Azure OpenAI, or any backend details. It just speaks AG-UI. You could swap the backend for a C# implementation or something else entirely – the frontend wouldn’t care. Besides of course the handling of specific tool calls.

Standard protocol: Because we use AG-UI, any AG-UI client can talk to this backend. We use CopilotKit in the frontend but you could use anything that speaks AG-UI. Take the Python client as an example.

Framework handles complexity: Streaming, tool calls, conversation history, protocol translation – Agent Framework does all of this. You just write business logic.

Easy to extend: Want a new tool? Write a function with @ai_function. Want a specialized agent? Create a ChatAgent and call .as_tool(). That’s it.

The AG-UI documentation explains that the protocol supports 7 different features including human-in-the-loop, generative UI, and shared state. Our simple backend gets all of these capabilities because Agent Framework implements the protocol.

Note that there are many more capabilities. Check the AG-UI interactive Dojo to find out: https://dojo.ag-ui.com/microsoft-agent-framework-python

Wrap Up

This is a simple but powerful pattern for building AI agent backends. You write minimal code and get a lot of functionality. AG-UI gives you a standard way to expose your agent, and Microsoft Agent Framework handles the implementation details.

If you want to try this yourself, the code is in the repo. You’ll need an Azure OpenAI deployment and follow the OAuth setup. After that, just run the code as instructed in the repo README!

The beauty is in the simplicity. Sometimes the best code is the code you don’t have to write.