In the previous post, I talked about options to build multi-agent solutions. The last option used Google’s A2A. A2A provides a wrapper around your agent, basically a JSON-RPC API, that standardizes how you talk to your agent. In this post we take a closer look at the basics of A2A with simple synchronous message exchange.

⚠️ A2A is still in development. We do not use it in production yet!

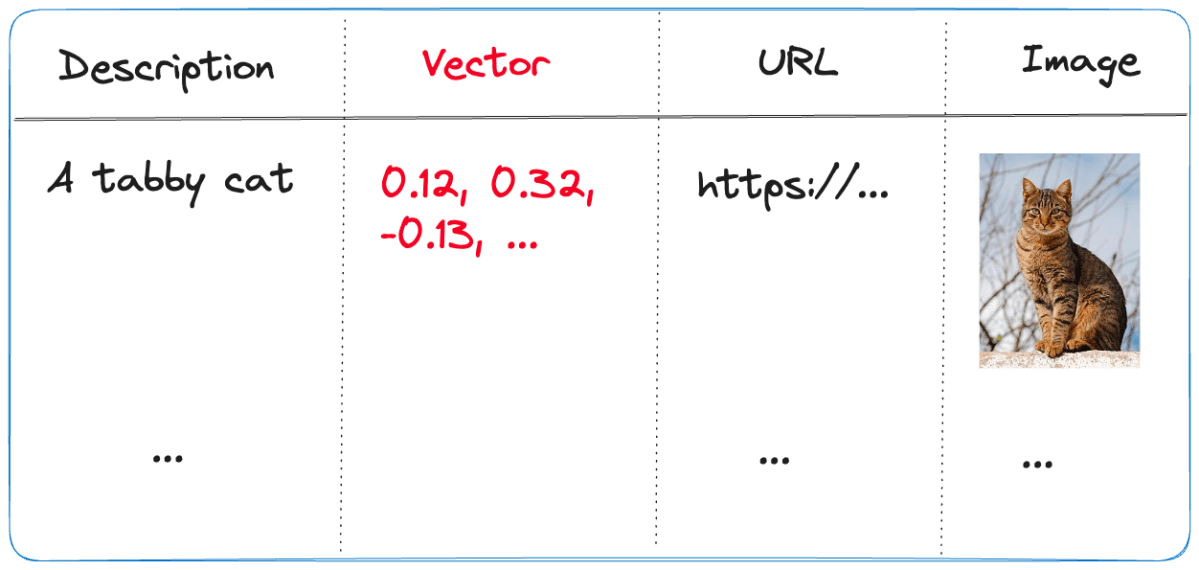

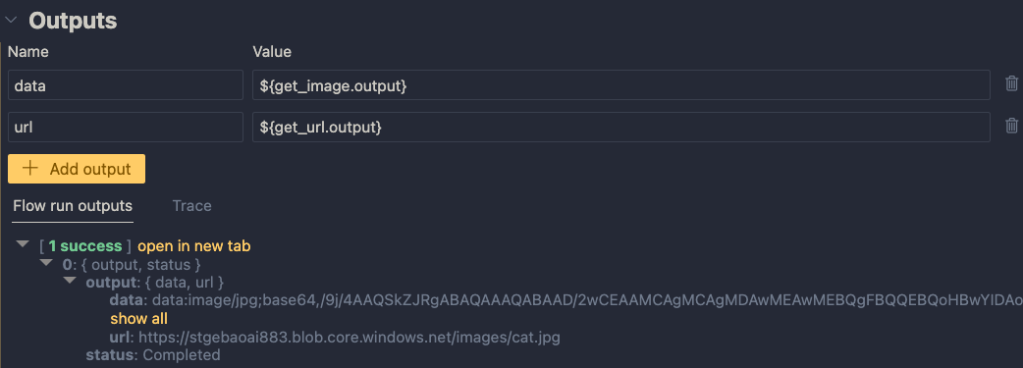

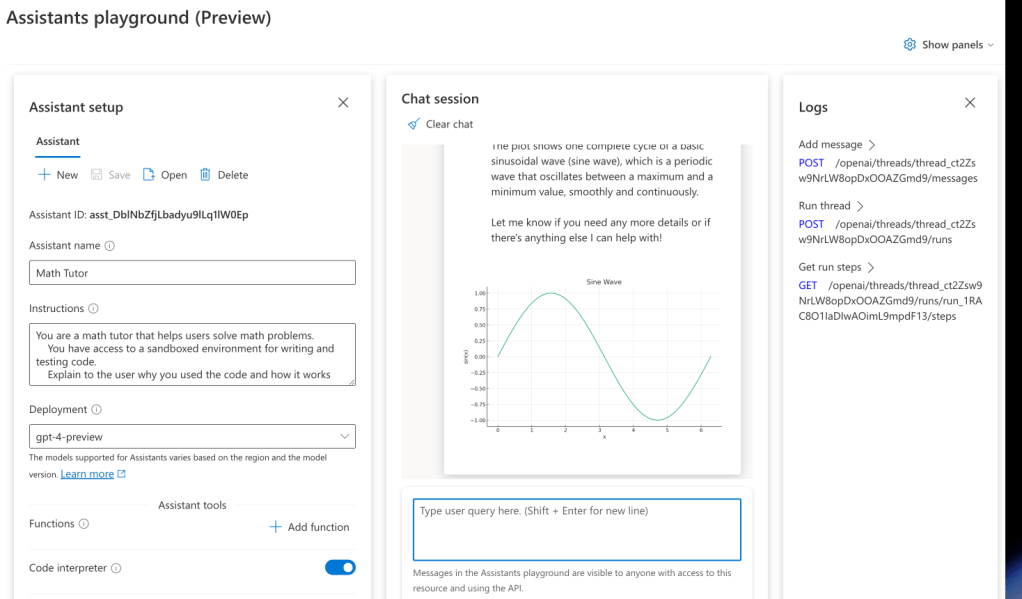

The idea is to build solutions that look like this (just one of the many possibilities):

The conversation agent is an agent that uses tools to get the job done. It wouldn’t be much of an agent without tools right? The tools are custom tools created by the developer that call other agents to do work. The other agents can be written in any framework and use any development language. How the agent works internally is irrelevant. When the conversation agent detects (via standard function calling) that the RAG tool needs to be executed, that tool will call the RAG agent over A2A and return the results.

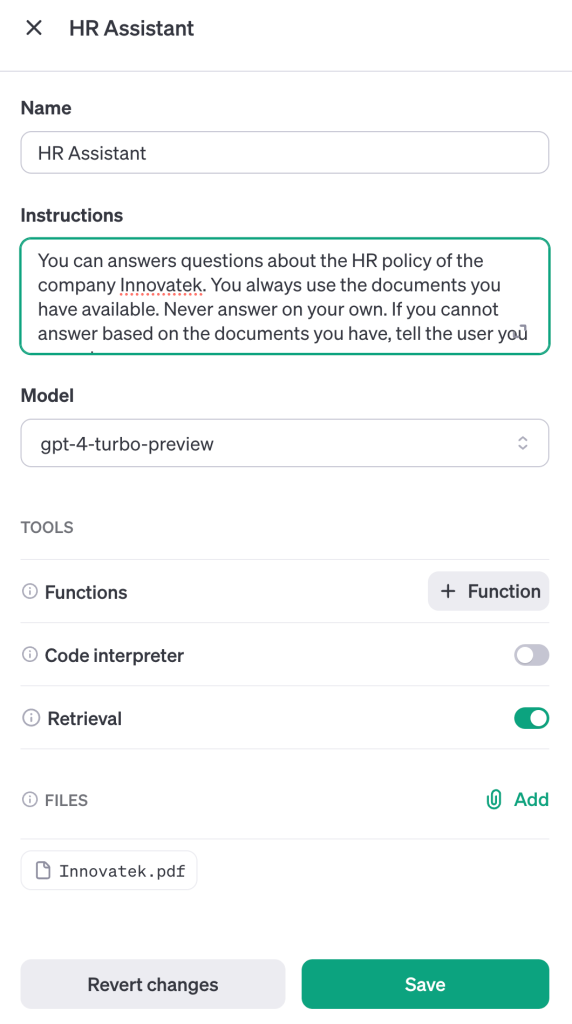

A2A does not dictate how you build your agent. In the example below, an Azure AI Foundry Agent sits at the core. That agent can use any of its hosted tools or custom tools to get the job done. Because this is a RAG Agent, it might use the built-in Azure AI Search or SharePoint knowledge source. As a developer, you use the Azure AI Foundry SDK or Semantic Kernel to interact with your agent as you see fit. Although you do not have to, it is common to wrap your agent in a class and provide one or more methods to interact with it. For example, an invoke() method and an invoke_streaming() method.

Here is a minimal example for the AI Foundry Agent (the yellow box):

class RAGAgent:

def __init__(self):

# INITIALIZATION CODE NOT SHOWN

self.project = AIProjectClient(

credential=DefaultAzureCredential(),

endpoint=endpoint)

self.agent = self.project.agents.get_agent(agent_id)

async def invoke(self, question: str) -> str:

thread = self.project.agents.threads.create()

message = self.project.agents.messages.create(

thread_id=thread.id,

role="user",

content=question

)

run = self.project.agents.runs.create_and_process(

thread_id=thread.id,

agent_id=self.agent.id)

messages = list(self.project.agents.messages.list(thread_id=thread.id, order=ListSortOrder.ASCENDING))

# ...

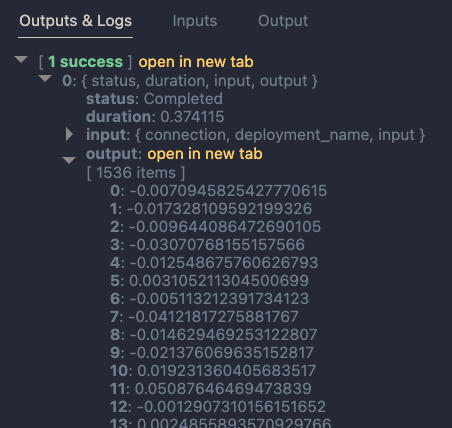

This code has nothing to do with Google A2A and could be implemented in many other ways. This is about to change because we will now call the above agent from A2A’s AgentExecutor. The AgentExecutor is a key server‑side interface: when a client sends a message, the A2A server calls execute() on your AgentExecutor instance, and your implementation handles the logic and sends updates via an event queue. Here’s how your agent is used by A2A. When a client sends a message it works its way down to your agent via several A2A components:

It’s important to understand the different types of message exchange in A2A. This post will not look at all of them. You can find more information in the A2A documentation. This post uses synchronous messaging via message/send where the response is a simple message and not a, potentially longer running, task.

Let’s dive into the AgentExecutor (it processes the message we send) and work our way up to the A2A client.

AgentExecutor

Let’s take a look at a bare bones implementation of AgentExecutor that works with plain/text input and output messages and without streaming:

Client --message--> A2A Server --> Agent Executor --> Agent

and

Agent --> Agent Executor --> A2A Server --message--> Client

class RAGAgentExecutor(AgentExecutor):

def __init__(self):

self.agent = RAGAgent()

async def execute(self, context: RequestContext, event_queue: EventQueue):

message_text = context.get_user_input()

result = await self.agent.invoke(message_text)

await event_queue.enqueue_event(new_agent_text_message(result))

async def cancel(self, context: RequestContext, event_queue: EventQueue):

raise Exception("Cancel not supported")

When a message is sent to the A2A server via JSON-RPC, the execute() method of the RAGAgentExecutor is called. At server startup, __init__ creates our AI Foundry RAGAgent which does the actual work.

Inside the execute() method, we assume the context contains a message. We use the get_user_input() helper to extract the message text (user query). We then simply call our agent’s invoke() method with that query and return the result via the event_queue. The A2A server uses an event_queue to provide responses back to the caller. In this case, the response will be a simple plain/text message.

This is probably as simple as it gets and is useful to understand A2A’s basic operation. In many cases though, you might want to return a longer running task instead of a message and provide updates to the client via streaming. That would require creating the task and streaming the task updates to the client. The client would need to be modified to handle this.

But wait, we still need to create the server that uses this AgentExecutor. Let’s take a look!

A2A Server

The A2A Python SDK uses starlette and uvicorn to create the JSON-RPC server. You don’t really need to know anything about this because A2A does this under the covers for you. The server needs to do a couple of things:

- Create one or more skills: skills represent a specific capability or function your agent offers—for instance, “currency conversion,” “document summary” or “meeting scheduling”.

- Create an agent card: an agent card is like a business card for your agent; it tells others what the agent can do; the above skills are part of the agent card; the agent card is published at

/.well-known/agent.jsonon the agents domain (e.g.,localhost:9999on your local machine) - Create a request handler: the request handler ties the server to the AgentExecutor you created earlier

- Create the A2AStarletteApplication: it ties the agent card and the request handler together

- Serve the A2AStarletteApplication with uvicorn on an address and port of your choosing

This is what it looks like in code:

import logging

import uvicorn

from a2a.server.apps import A2AStarletteApplication

from a2a.server.request_handlers import DefaultRequestHandler

from a2a.server.tasks import InMemoryTaskStore

from a2a.types import AgentCapabilities, AgentCard, AgentSkill

from agent_executor import RagAgentExecutor

def main():

skill = AgentSkill(

id="rag_skill",

name="RAG Skill",

description="Search knowledge base for project information",

tags=["rag", "agent", "information"],

examples=["What is project Astro and what tech is used in it?"],

)

agent_card = AgentCard(

name="RAG Agent",

description="A simple agent that searches the knowledge base for information",

url="http://localhost:9998/",

defaultInputModes=["text"],

defaultOutputModes=["text"],

skills=[skill],

version="1.0.0",

capabilities=AgentCapabilities(),

)

request_handler = DefaultRequestHandler(

agent_executor=RagAgentExecutor(),

task_store=InMemoryTaskStore(),

)

server = A2AStarletteApplication(

http_handler=request_handler,

agent_card=agent_card,

)

uvicorn.run(server.build(), host="0.0.0.0", port=9998)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

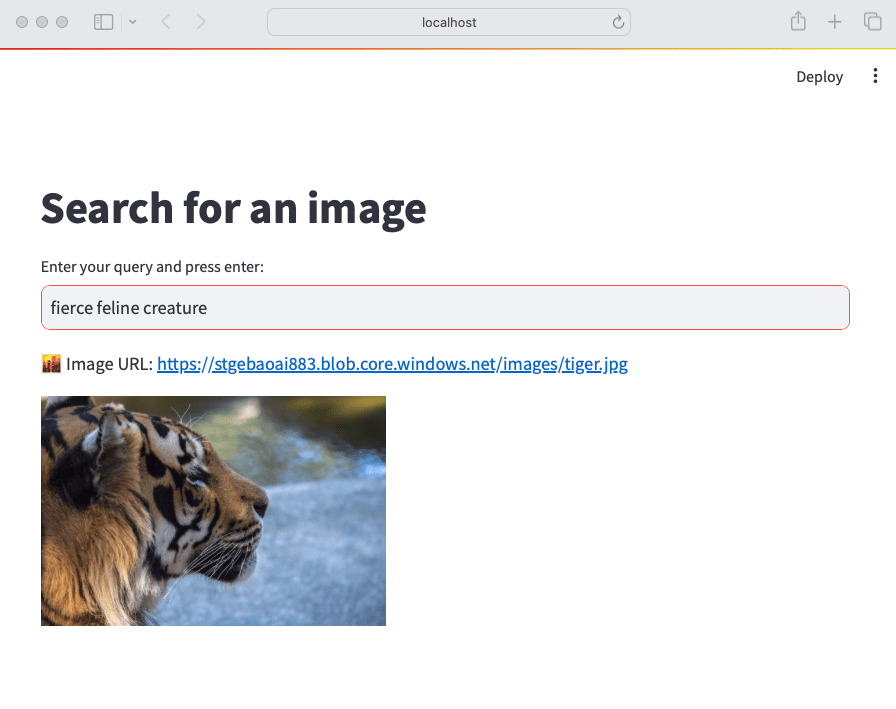

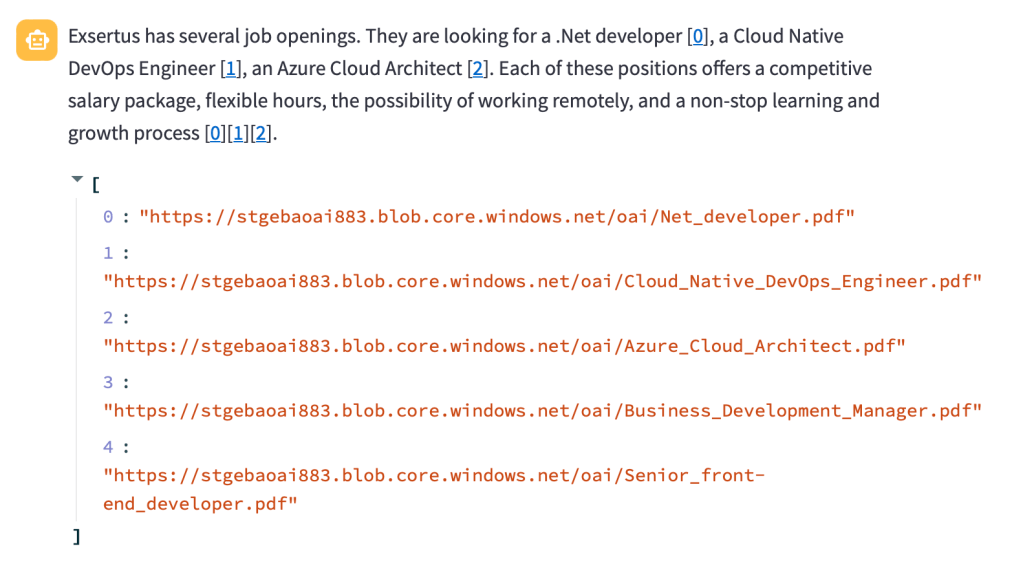

Validating the agent card

When you run the A2A server on your local machine and expose it to the public with ngrok or other tools, you can use https://a2aprotocol.ai/a2a-protocol-validator to validate it. When I do this for the RAG Agent, I get the following:

In JSON, the agent card is as follows:

{

"capabilities": {},

"defaultInputModes": [

"text"

],

"defaultOutputModes": [

"text"

],

"description": "A simple agent that searches the knowledge base for information",

"name": "RAG Agent",

"protocolVersion": "0.2.5",

"skills": [

{

"description": "Search knowledge base for project information",

"examples": [

"What is project Astro and what tech is used in it?"

],

"id": "rag_agent",

"name": "RAG Agent",

"tags": [

"rag",

"agent",

"information"

]

}

],

"url": "http://Geerts-MacBook-Air-2.local:9998/",

"version": "1.0.0"

}

Now it is time to actually start talking to the agent.

Using the A2A client to talk to the agent

With the server up and running and the Agent Card verified, how do we exchange messages with the server?

In our case, where the server supports only text and there is no streaming, the client can be quite simple:

- Create an

httpxclient and set timeout higher depending on how long it takes to get a response; this client is used by theA2ACardResolverandA2AClient - Retrieve the agent card with the

A2ACardResolver - Create a client with

A2AClient. It needs the agent card as input and will use theurlin the agent card to connect to the A2A server - Create a

Message, include it in aMessageRequestand send theMessageRequestwith the client. We use the non-streamingmessage_send()method. - Handle the response from the client

The code below shows what this might look like:

import uuid

import httpx

from a2a.client import A2ACardResolver, A2AClient

from a2a.types import (

AgentCard,

Message,

MessageSendParams,

Part,

Role,

SendMessageRequest,

TextPart,

)

PUBLIC_AGENT_CARD_PATH = "/.well-known/agent.json"

BASE_URL = "http://localhost:9998"

async def main() -> None:

timeout = httpx.Timeout(200.0, read=200.0, write=30.0, connect=10.0)

async with httpx.AsyncClient(timeout=timeout) as httpx_client:

# Initialize A2ACardResolver

resolver = A2ACardResolver(

httpx_client=httpx_client,

base_url=BASE_URL,

)

final_agent_card_to_use: AgentCard | None = None

try:

print(

f"Fetching public agent card from: {BASE_URL}{PUBLIC_AGENT_CARD_PATH}"

)

_public_card = await resolver.get_agent_card()

print("Fetched public agent card")

print(_public_card.model_dump_json(indent=2))

final_agent_card_to_use = _public_card

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error fetching public agent card: {e}")

raise RuntimeError("Failed to fetch public agent card")

client = A2AClient(

httpx_client=httpx_client, agent_card=final_agent_card_to_use

)

print("A2AClient initialized")

message_payload = Message(

role=Role.user,

messageId=str(uuid.uuid4()),

parts=[Part(root=TextPart(text="Is there a project with the word Astro? If so, describe it."))],

)

request = SendMessageRequest(

id=str(uuid.uuid4()),

params=MessageSendParams(

message=message_payload,

),

)

print("Sending message")

response = await client.send_message(request)

print("Response:")

print(response.model_dump_json(indent=2))

if __name__ == "__main__":

import asyncio

asyncio.run(main())

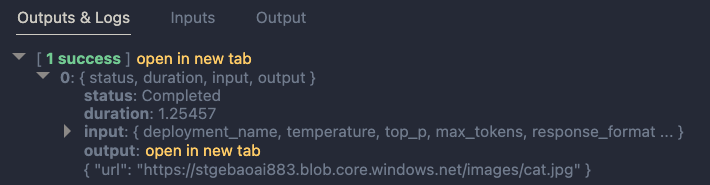

Above, the entire response is printed as JSON. That is useful to learn what the responses look like. This is part of the response:

{

"id": "6cc795d8-fa84-4734-8b5a-dccd3a22142d",

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"result": {

"contextId": null,

"extensions": null,

"kind": "message",

"messageId": "fead200d-0ea4-4ccb-bf1c-ed507b38d79d",

"metadata": null,

"parts": [

{

"kind": "text",

"metadata": null,

"text": "RESPONSE FROM RAG AGENT"

}

],

"referenceTaskIds": null,

"role": "agent",

"taskId": null

}

}

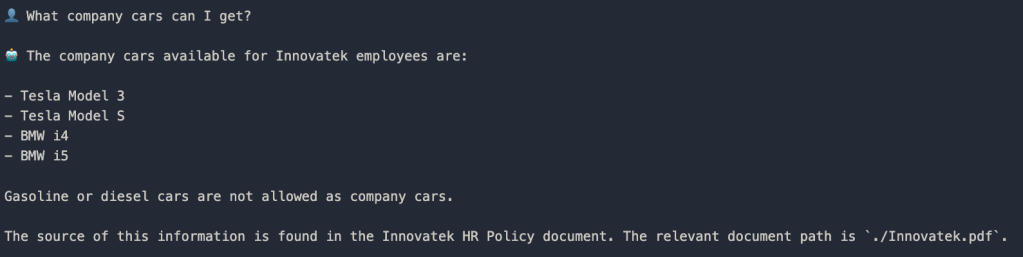

Simply sending the response as a string on the event queue results in a message with one text part. The result from the RAG agent is in the text property. For a longer running task with streaming updates, the response would be quite different.

You can now easily interact with your agent using this client. For example:

- use the client in any application (need not be an agent)

- use the client in a workflow engine like LangGraph

- use the client in an agent tool; the agent can be written in any framework; when the agent identifies a tool call is needed, the tool is run which contains A2AClient code to interact with the A2A Agent

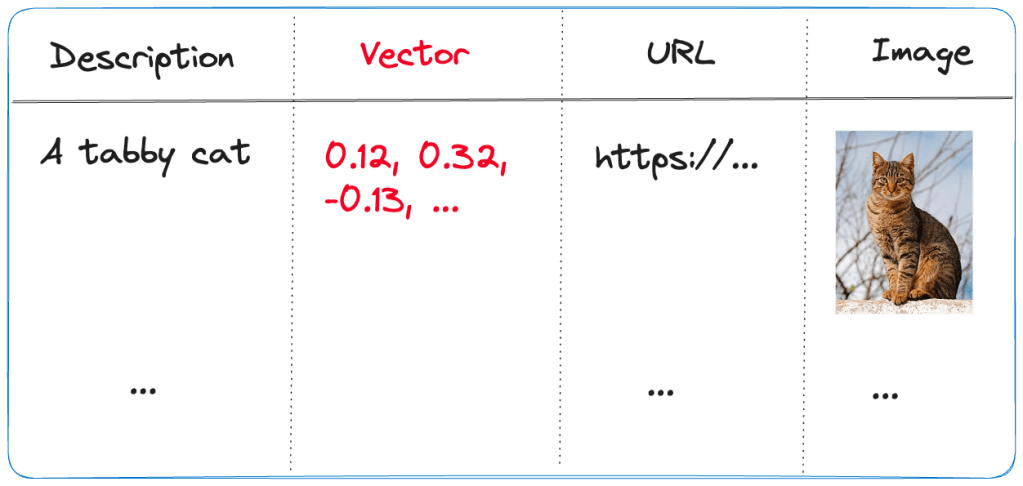

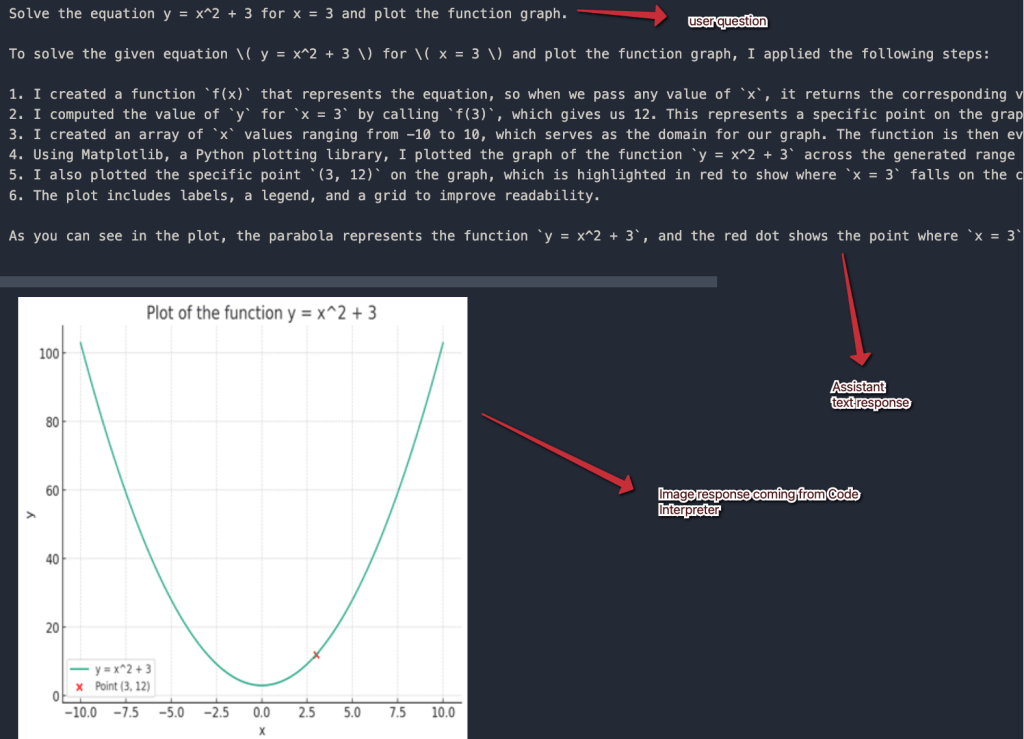

The entire flow

The diagram below shows the end-to-end flow:

Try it yourself

On GitHub, check https://github.com/gbaeke/multi_agent_aca/tree/main/a2a_simple for a skeleton implementation of a calculator agent. The CalculatorAgent class’s invoke() method always returns “I did not do anything!” It’s up to you to change that!

You can run this A2A server as-is and connect to it with test_client.py. To use an actual agent, update the CalculatorAgent class’s invoke() method with a real agent written in your preferred framework.

Check the README.md for more instructions.

That’s it for this post! In a next one, we will look at a more complex example that streams messages to the client. Stay tuned!