If you follow me on LinkedIn, you know I have talked about agentic workflows versus agents. Although everybody talks about agents, workflows are often better suited to many tasks. A workflow is more deterministic, is easier to reason about and to troubleshoot. Anthropic also talked about this a while ago in Building Effective Agents.

In fact, I often see people create tool-calling agents (e.g., in Copilot Studio) with instructions to call the tools in a specific order. For example: check if a mail is a complaint and if so, draft an e-mail response. Although this simple task will probably work with a non-deterministic agent, a workflow is better suited.

The question then becomes, how do you write the workflow? Simple workflows can easily be coded yourself. Instead of writing code, you might use a visual builder like Power Automate, Agent Flows in Copilot Studio, Logic Apps, n8n, make and many others.

But what if you need to write robust workflows that are more complex, need to scale, are long-running and need to pick up where they left off in case of failure? In that case, a durable execution engine might be a good fit. There are many such solutions on the market: restate, Temporal and many others, including several options in Azure.

Before we dive into how we can write such a workflow in Azure, let’s look at how one vendor, restate, defines durable execution:

Durable Execution is the practice of making code execution persistent, so that services recover automatically from crashes and restore the results of already completed operations and code blocks without re-executing them.

(from https://restate.dev/what-is-durable-execution/)

Ok, enough talk. Let’s see who we can write a workflow that uses durable execution. The example we use is kept straightforward to not get lost in the details:

- I have a list of articles

- Each article needs to be summarized. The summaries will be used in a later step to create a newsletter. We will use gpt-4.1-mini to create the summaries in parallel.

- When the summaries are ready, we create a newsletter in HTML.

- When the newsletter is ready, we will e-mail it to subscribers. There’s only one subscriber here, me! 🤷♂️

All code is here: https://github.com/gbaeke/dts_ai

Azure Durable Task Scheduler

There are several options for durable execution in Azure. One option is to use the newer Durable Task Scheduler in combination with the Durable Task SDKs. Another option is Durable Functions. These functions can also use the Durable Task Scheduler as the back-end.

The Durable Task Scheduler is the ❤️ heart of the solution as it keeps track of the different tasks in an orchestration (or workflow). On failure, it retains state, marking completed tasks and queuing pending ones to complete the orchestration. Note that the scheduler does not execute the tasks. That’s the job of a worker. Workers connect to the scheduler in order to complete the orchestration. The code in your worker does the actual processing like making LLM calls or talking to other systems.

The code you write (e.g., for the worker) uses the Durable Task SDK in your language of choice. I will use Python in this example.

For local development, you can use the Durable Task Scheduler emulator by running the following Docker container:

docker run --name dtsemulator -d -p 8080:8080 -p 8082:8082 mcr.microsoft.com/dts/dts-emulator:latest

Your code will connect to the emulator on port 8080. Port 8082 presents an administrative UI to check and interact with orchestrations:

Later, you can deploy the Durable Task Scheduler in Azure and use that instead of the local emulator.

Let’s build locally

As discussed about, we will create a workflow that takes articles as input, generates summaries, creates a newsletter and sends it via e-mail. With three articles, the following would happen:

The final newsletter looks something like this:

Don’t worry, I won’t send actual AI slop newsletters to you! 😊

To get started, we need to start the Durable Task Scheduler locally using this command (requires Docker):

docker run --name dtsemulator -d -p 8080:8080 -p 8082:8082 mcr.microsoft.com/dts/dts-emulator:latest

Next, we need a worker. The worker defines one or more activities in addition to one or more orchestrations that use these activities. Our worker has three activities:

process_article: takes in an article and returns a summary generated by gpt-4.1-mini; no need for a fancy agent framework, we simply use the OpenAI SDKaggregate_results: takes in a list of summaries and generates the HTML newsletter using gpt-4.1-mini.send_email: e-mails the newsletter to myself with Resend

These activities are just Python functions. The process_article function is shown below:

def process_article(ctx, text: str) -> str:

"""

Activity function summarizes the given text.

"""

logger.info(f"Summarizing text: {text}")

wrapper = AgentWrapper()

summary = wrapper.summarize(text)

return summary

Easy does it I guess!

Next, the worker defines an orchestration function. The orchestration takes in the list of articles and contains code to run the activities as demanded by your workflow:

def fan_out_fan_in_orchestrator(ctx, articles: list) -> Any:

# Fan out: Create a task for each article

parallel_tasks = []

for article in articles:

parallel_tasks.append(ctx.call_activity("process_article", input=article))

# Wait for all tasks to complete

results = yield task.when_all(parallel_tasks)

# Fan in: Aggregate all the results

html_mail = yield ctx.call_activity("aggregate_results", input=results)

# Send email

email_request = EmailRequest(

to_email=to_address,

subject="Newsletter",

html_content=html_mail,

)

email = yield ctx.call_activity("send_email", input=asdict(email_request))

return "Newsletter sent"

When an orchestration runs an activity with call_activity, a task is returned. For each article, such a task is started with all tasks stored in the parallel_tasks list. The when_all helper yields the results of these tasks to the results lists until all tasks are finished. After that, we can pass results (a list of strings) to the aggregate_results activity and send a mail with the send_email activity.

⚠️ I use a dataclass to provide the send_email activity the required parameters. Check the full source code for more details.

The worker is responsible for connecting to the Durable Task Scheduler and registering activities and orchestrators. The snippet below illustrates this:

with DurableTaskSchedulerWorker(

host_address=endpoint,

secure_channel=endpoint != "http://localhost:8080",

taskhub=taskhub_name,

token_credential=credential

) as worker:

# Register activities and orchestrators

worker.add_activity(process_article)

worker.add_activity(aggregate_results)

worker.add_activity(send_email)

worker.add_orchestrator(fan_out_fan_in_orchestrator)

# Start the worker (without awaiting)

worker.start()

When you use the emulator, the default address is http://localhost:8080 with credential set to None. In Azure, you will use the provided endpoint and RBAC to authenticate (e.g., managed identity of a container app).

Full code of the worker is here.

Now we just need a client that starts an orchestration with the input it requires. In this example we use a Python script that reads articles from a JSON file. The client then connects to the Durable Task Scheduler to kick off the orchestration. Here is the core snippet that does the job:

client = DurableTaskSchedulerClient(

host_address=endpoint,

secure_channel=endpoint != "http://localhost:8080",

taskhub=taskhub_name,

token_credential=credential

)

instance_id = client.schedule_new_orchestration(

"fan_out_fan_in_orchestrator",

input=articles # simply a list of strings

)

result = client.wait_for_orchestration_completion(

instance_id,

timeout=120

)

# check runtime_status of result, grab serialized_result, etc...

Above, the client waits for 120 seconds before it times out.

⚠️ There are many ways to follow up on the results of an orchestration. This script uses a simple approach with a timeout. When there is a timeout, the script stops but the orchestration continues.

Full code of the client is here.

Checking if it works

Before we can run a test, ensure you started the Durable Task Scheduler emulator. Next, clone this repository:

From the root of the cloned folder, create a Python virtual environment:

python3 -m venv .venv

Activate the environment:

source .venv/bin/activate

cd into the src folder and install from requirements:

pip install -r requirements.txt

Ensure you have a .env in the root:

OPENAI_API_KEY=Your OpenAI API key

RESEND_API_KEY=Your resend API key

FROM_ADDRESS=Your from address (e.g. NoReply <noreply@domain.com>)

TO_ADDRESS=Your to address

Now run the worker with python worker.py. You should see the following:

INFO:__main__:Starting Fan Out/Fan In pattern worker...

Using taskhub: default

Using endpoint: http://localhost:8080

2025-08-14 22:11:10.851 durabletask-worker INFO: Starting gRPC worker that connects to http://localhost:8080

2025-08-14 22:11:10.882 durabletask-worker INFO: Created fresh connection to http://localhost:8080

2025-08-14 22:11:10.882 durabletask-worker INFO: Successfully connected to http://localhost:8080. Waiting for work items...

The worker is waiting for work items. We will submit them from our client.

From the same folder, in another terminal, run the client with python client.py. It will use the sample articles_short.json file.

INFO:__main__:Starting Fan Out/Fan In pattern client...

Using taskhub: default

Using endpoint: http://localhost:8080

INFO:__main__:Loaded 11 articles from articles.json

INFO:__main__:Starting new fan out/fan in orchestration with 11 articles

2025-08-14 22:25:02.946 durabletask-client INFO: Starting new 'fan_out_fan_in_orchestrator' instance with ID = '3a1bb4d9e3f240dda33daf982a5a3882'.

INFO:__main__:Started orchestration with ID = 3a1bb4d9e3f240dda33daf982a5a3882

INFO:__main__:Waiting for orchestration to complete...

2025-08-14 22:25:02.969 durabletask-client INFO: Waiting 120s for instance '3a1bb4d9e3f240dda33daf982a5a3882' to complete.

When the orchestration completes, the client outputs the result. That is simply Newsletter sent. 🤷♂️

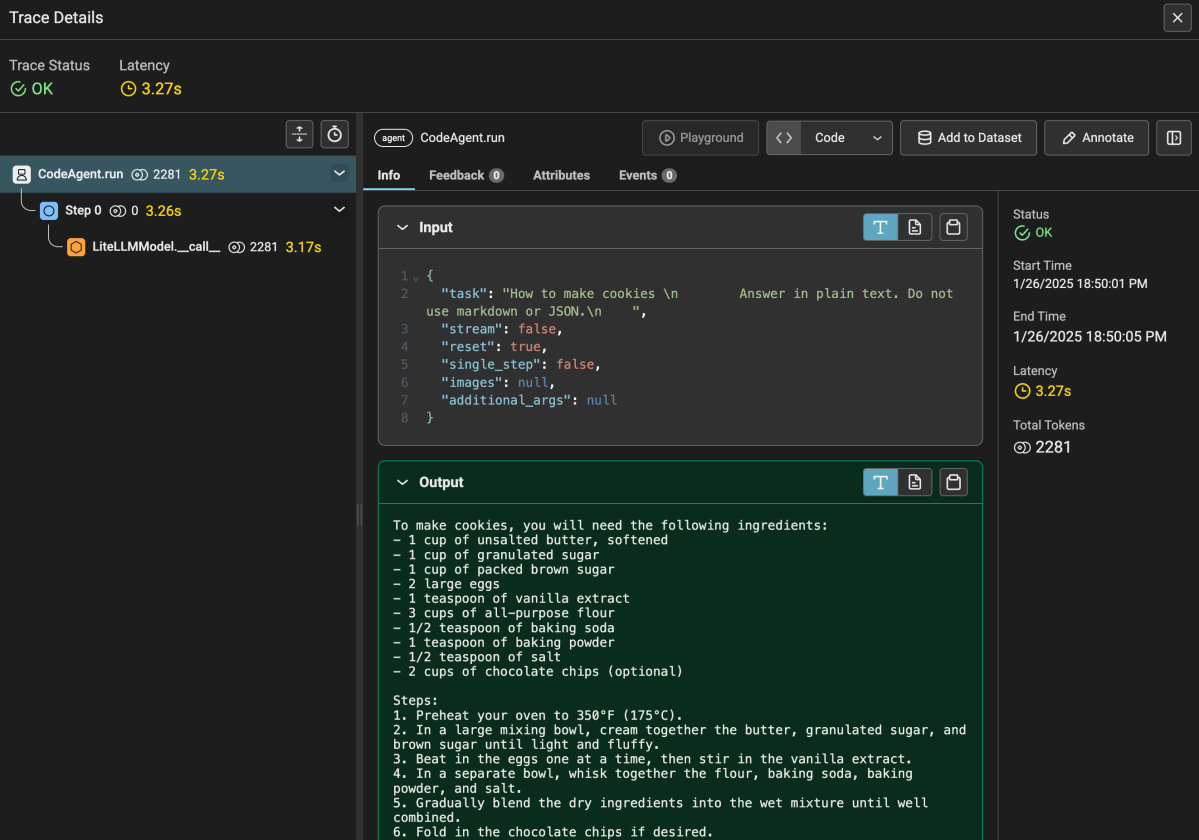

You can see the orchestration in action by going to http://localhost:8082. Select the task hub default and click your orchestration at the top. In the screenshot below, the orchestration was still running and busy aggregating results.🤷♂️

An interesting thing to try is to kill the worker while it’s busy processing. When you do that, the client will eventually timeout with a TimeoutError (if you wait long enough). If you check the portal, the orchestration will stay in a running state. However, when you start the worker again, it will restart where it left off:

INFO:__main__:From address: baeke.info <noreply@baeke.info>

INFO:__main__:To address: Geert Baeke <geert@baeke.info>

INFO:__main__:Starting Fan Out/Fan In pattern worker...

Using taskhub: default

Using endpoint: http://localhost:8080

2025-08-14 23:14:22.979 durabletask-worker INFO: Starting gRPC worker that connects to http://localhost:8080

2025-08-14 23:14:23.003 durabletask-worker INFO: Created fresh connection to http://localhost:8080

2025-08-14 23:14:23.004 durabletask-worker INFO: Successfully connected to http://localhost:8080. Waiting for work items...

INFO:__main__:Aggregating 4 summaries

I killed my worker when it was busy aggregating the summaries. When the worker got restarted, the aggregation started again and used the previously saved state to get to work again. Cool! 😎

Wrapping Up!

In this post we created a durable workflow with the Durable Task Scheduler emulator running on a local machine. We used the Durable Task SDK for Python to create a worker that is able to run an orchestration that aggregates multiple summaries into a newsletter. We demonstrated that such a workflow survives worker crashes and that it can pick up where it left off.

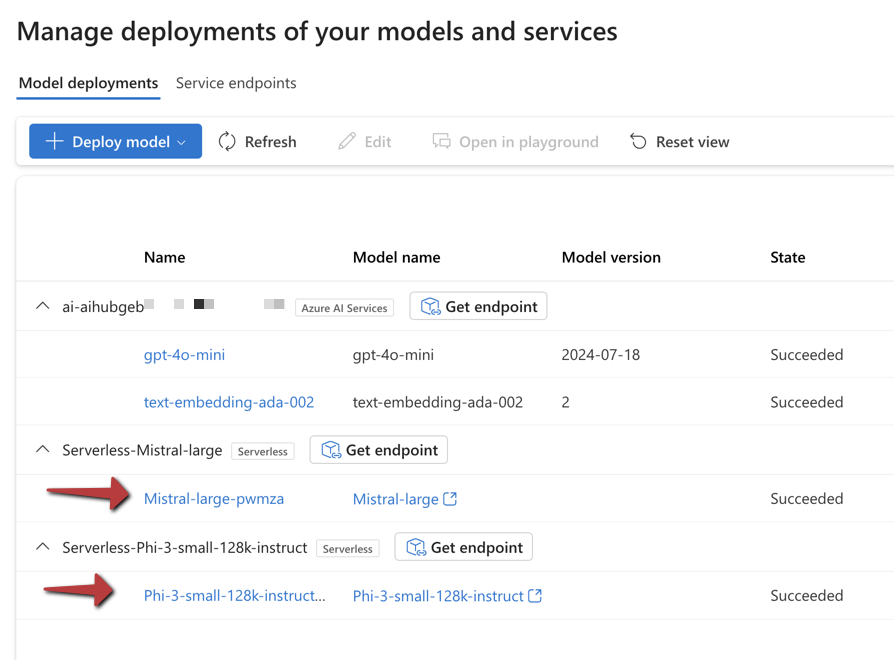

However, we have only scratched the surface here. Stay tuned for another post that uses Durable Task Scheduler in Azure together with workers and clients in Azure Container Apps.