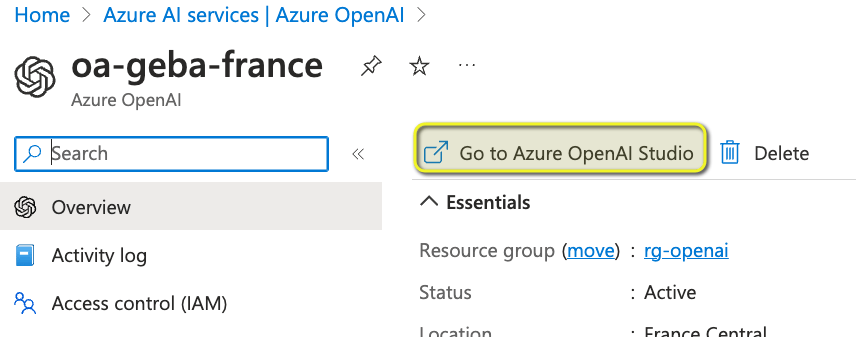

In a previous post, I discussed the Microsoft Bot Framework SDK that provides a fast track to deploying intelligent bots with the help of the Assistants API. Yet, the journey doesn’t stop there. Copilot Studio, a low-code tool, introduces an even more efficient approach, eliminating the need for intricate bot coding. It empowers developers to quickly design and deploy bots, focusing on functionality over coding complexities.

In this post, we will combine Copilot Studio with the Assistants API. But first, let’s take a quick look at the basics of Copilot Studio.

Copilot Studio

Copilot Studio, known before as Power Virtual Agents, is part of Microsoft’s Power Platform. It allows anyone to create a bot fast with it’s intent-based authoring experience. To try it out, just click the Try Free button on the Copilot Studio web page.

Note: I will not go into licensing here. I do not have a Phd in Power Platform Licensing yet! 😉

When you create a new bot, you will get the screen below:

You simply give your bot a name and a language. Right from the start, you can add Generative AI capabilities by providing a website URL. If that website is searchable by Bing, users can ask questions about content on that website.

However, this does not mean Copilot Studio can carry a conversation like ChatGPT. It simply means that, when Copilot Studio cannot identify an intent, it will search the website for answers and provide the answer to you. You can ask follow-up questions but it’s not a full ChatGPT experience. For example, you cannot say “Answer the following questions in bullet style” and expect the bot to remember that. It will simply throw an error and try to escalate you to a live agent after three tries.

Note: this error & escalate mechanism is a default; you can change that if you wish

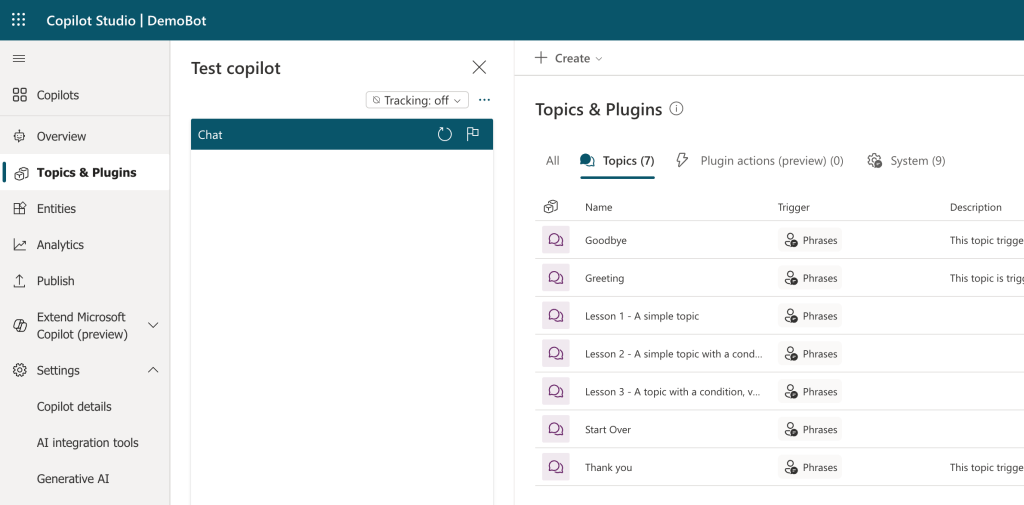

So what is an intent? If you look at the screenshot below, you will see some out of the box topics available to your bot.

Above, you see a list of topics and plugins. I have not created any plugins so there are only topics: regular topics and system topics. Whenever you send a message, the system tries to find out what your intent is by checking matching phrases defined in a trigger.

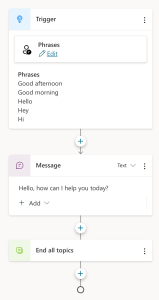

If you click on the Greeting topic, you will see the following:

This topic is triggered by a number of phrases. When the user sends a message like Hi!, that message will match the trigger phrases (intent is known). A response message will be sent back: “Hello, how can I help you today?”.

It’s important to realise that no LLM (large language model) is involved here. Other machine learning stuff is at play here.

The behaviour is different when I send a message that is not matched to any of the topics. Because I setup the bot with my website (https://atomic-temporary-16150886.wpcomstaging.com), the following happens when I ask: “What is the OpenAI Assistants API?”

Check the topic above. We are in the Conversational Boosting topic now. It was automatically created when I added my website in the Generative Answers section during creation:

If you look closely, you will notice that the trigger is set to On Unknown Intent. This means that this topic is used whenever you type something that cannot be matched to other topics. Behind the scenes, the system searches the website and returns a summary of the search to you, totally driven by Azure OpenAI. You do not need an Azure OpenAI resource to enable this.

This mixing and matching of intents is interesting in several ways:

- you can catch specific intents and answer accordingly without using an OpenAI model: for example, when a user wants to book a business trip, you can present a form which will trigger an API that talks to an internal booking system

- to answer from larger knowledge bases, you can add either use a catch-all such as the Conversational Boosting topic or even use custom intents that use the Create Generative Answers node to go to any supported data source

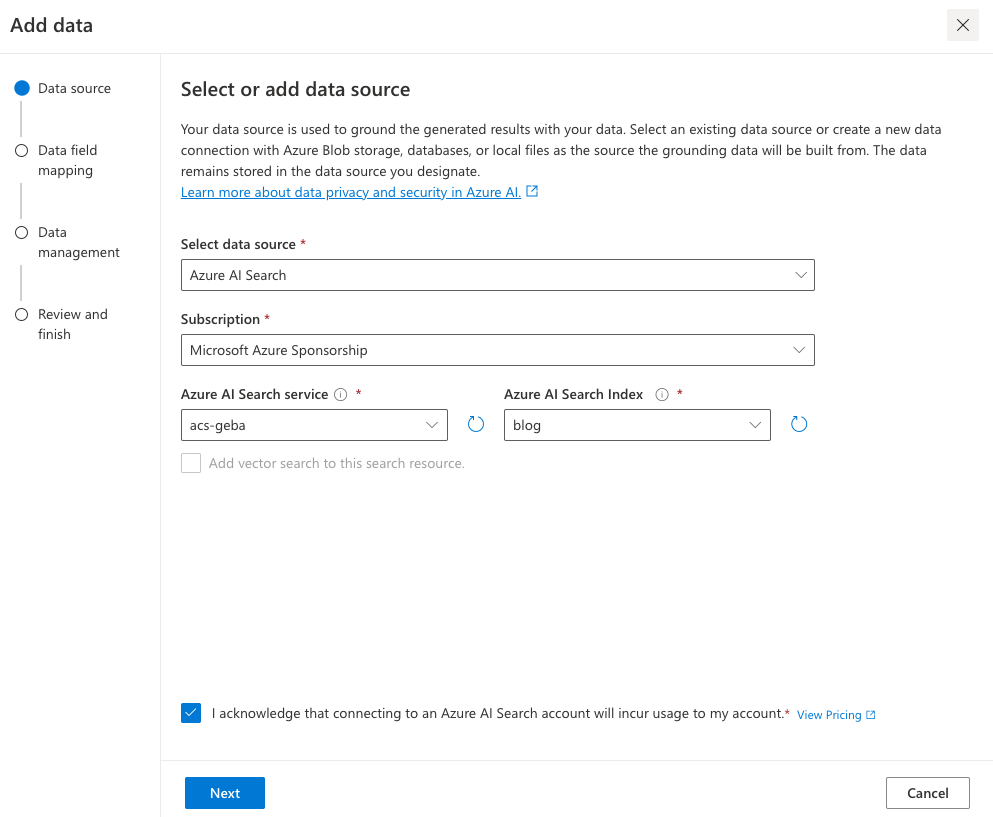

Besides web sites, other data sources are supported such as SharePoint, custom documents or even Azure OpenAI Add your data.

What we want to do is different. We want to use Copilot Studio to provide a full ChatGPT experience. We will not need Generative Answers to do so. Instead, we will use the OpenAI Assistants API behind the scenes.

Copilot Studio and Azure OpenAI Assistants

We want to achieve the following:

- When a new conversation is started: create a new tread

- When the user sends a message: add the message to the thread, run the thread and send the response back to Copilot Studio.

- When the user asks to start over, start a new conversation which starts a new thread

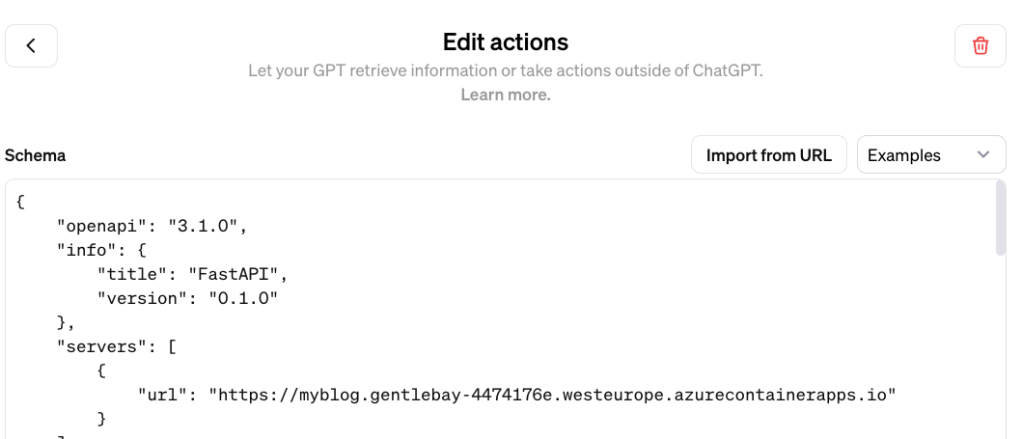

One way of doing this, is to write a small API that can create a thread and add messages to it. Here’s the API I wrote using Python FastAPI:

from fastapi import FastAPI, Depends, HTTPException, status

from fastapi.security.api_key import APIKeyHeader, APIKey

from pydantic import BaseModel

import logging

import uvicorn

from openai import AzureOpenAI

from dotenv import load_dotenv

import os

import time

import json

load_dotenv("../.env")

# Configure logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

# Define API key header; set it in ../.env

API_KEY = os.getenv("API_KEY")

# Check for API key

if API_KEY is None:

raise ValueError("API_KEY environment variable not set")

API_KEY_NAME = "access_token"

api_key_header = APIKeyHeader(name=API_KEY_NAME, auto_error=True)

async def get_api_key(api_key_header: str = Depends(api_key_header)):

if api_key_header == API_KEY:

return api_key_header

else:

raise HTTPException(

status_code=status.HTTP_403_FORBIDDEN, detail="Could not validate credentials"

)

app = FastAPI()

# Pydantic models

class MessageRequest(BaseModel):

message: str

thread_id: str

class MessageResponse(BaseModel):

message: str

class ThreadResponse(BaseModel):

thread_id: str

# set the env vars below in ../.env

client = AzureOpenAI(

api_key=os.getenv('AZURE_OPENAI_API_KEY'),

azure_endpoint=os.getenv('AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT'),

api_version=os.getenv('AZURE_OPENAI_API_VERSION')

)

# this refers to an assistant without functions

assistant_id = "asst_fRWdahKY1vWamWODyKnwtXxj"

def wait_for_run(run, thread_id):

while run.status == 'queued' or run.status == 'in_progress':

run = client.beta.threads.runs.retrieve(

thread_id=thread_id,

run_id=run.id

)

time.sleep(0.5)

return run

# Example endpoint using different models for request and response

@app.post("/message/", response_model=MessageResponse)

async def message(item: MessageRequest, api_key: APIKey = Depends(get_api_key)):

logger.info(f"Message received: {item.message}")

# Send message to assistant

message = client.beta.threads.messages.create(

thread_id=item.thread_id,

role="user",

content=item.message

)

run = client.beta.threads.runs.create(

thread_id=item.thread_id,

assistant_id=assistant_id # use the assistant id defined aboe

)

run = wait_for_run(run, item.thread_id)

if run.status == 'completed':

messages = client.beta.threads.messages.list(limit=1, thread_id=item.thread_id)

messages_json = json.loads(messages.model_dump_json())

message_content = messages_json['data'][0]['content']

text = message_content[0].get('text', {}).get('value')

return MessageResponse(message=text)

else:

return MessageResponse(message="Assistant reported an error.")

@app.post("/thread/", response_model=ThreadResponse)

async def thread(api_key: APIKey = Depends(get_api_key)):

thread = client.beta.threads.create()

logger.info(f"Thread created with ID: {thread.id}")

return ThreadResponse(thread_id=thread.id)

# Uvicorn startup

if __name__ == "__main__":

uvicorn.run(app, host="127.0.0.1", port=8324)

Note: you can find this code on GitHub as well: https://github.com/gbaeke/azure-assistants-api/tree/main/api

Some things to note here:

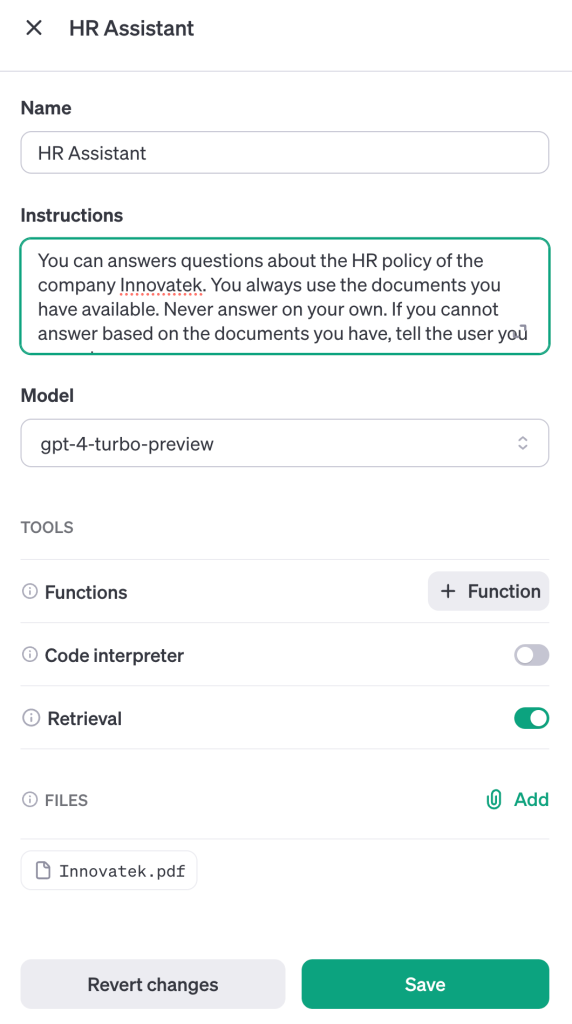

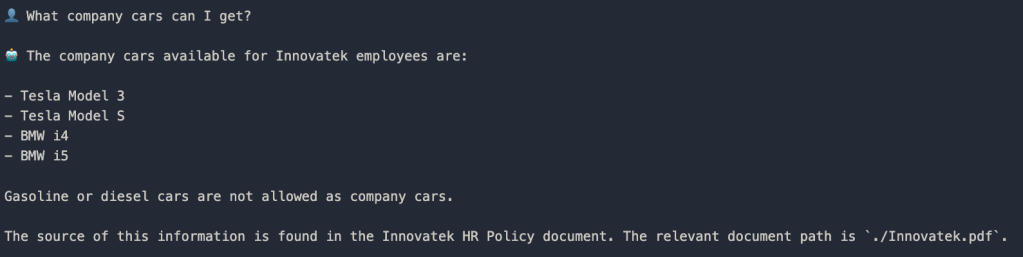

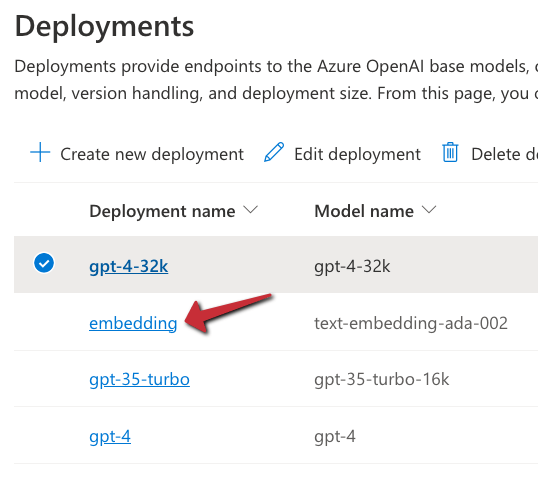

- I am using an assistant I created in the Azure OpenAI Assistant Playground and reference it by its ID; this assistant does not use any tools or files

- I require an API key via a custom HTTP header

access_token; later Copilot Studio will need this key to authenticate to the API - I define two methods:

/threadand/message

If you have followed the other posts about the Assistants API, the code should be somewhat self-explanatory. The code focuses on the basics so not a lot of error checking for robustness.

If you run the above code, you can use a .http file in Visual Studio Code to test it. This requires the REST Client extension. Here’s the file:

POST http://127.0.0.1:8324/message

Content-Type: application/json

access_token: 12345678

{

"message": "How does Copilot Studio work?",

"thread_id": "thread_S2mwvse5Zycp6BOXNyrUdlaK"

}

###

POST http://127.0.0.1:8324/thread

Content-Type: application/json

access_token: 12345678

In VS Code, with the extension loaded, you will see Send Request links above the POST commands. Click them to execute the requests. Click the thread request first and use the thread ID from the response in the body of the message request.

After you verified that it works, we can expose the API to the outside world with ngrok.

Using ngrok

If you have never used ngrok, download it for your platform. You should also get an authtoken by signing up and providing it to ngrok.

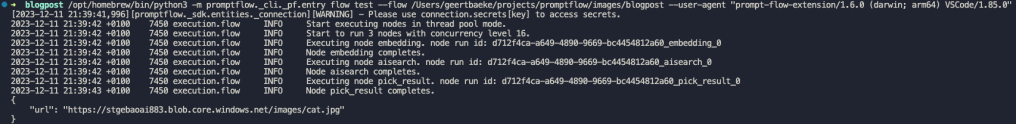

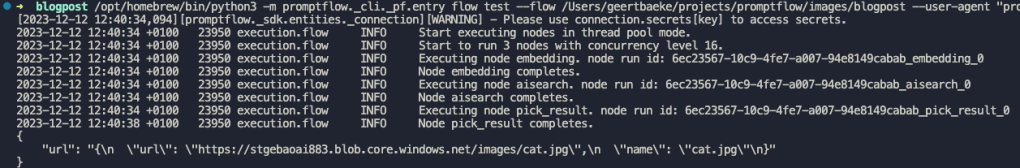

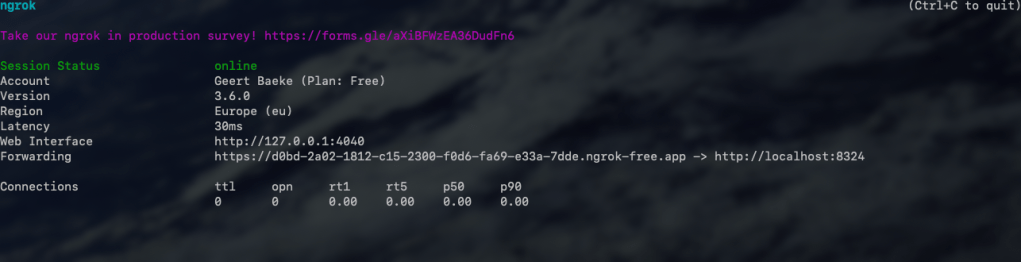

When the API is running, in a terminal window, type ngrok http 8324. You should see something like:

Check the forwarding URL. This is a public URL you can use. We will use this URL from Copilot Studio.

Note: in reality, we would publish this API to container apps or another hosting platform

Using the API from Copilot Studio

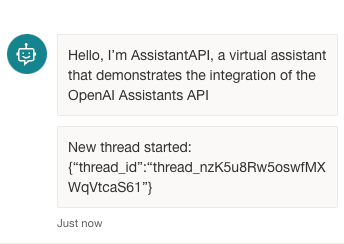

In Copilot Studio, I created a new bot without generative answers. The first thing we need to do is to create a thread when a new conversation starts:

In the UI, it looks like below:

You can use the Conversation Start system topic to create the thread. The first section of the topic looks like below:

Above there are three nodes:

- Trigger node: On Conversation Start

- Message: welcoming the user

- Set variable: a global variable is set that’s available to all topics; the variable holds the URL of the API to call; that is the ngrok public url in this case

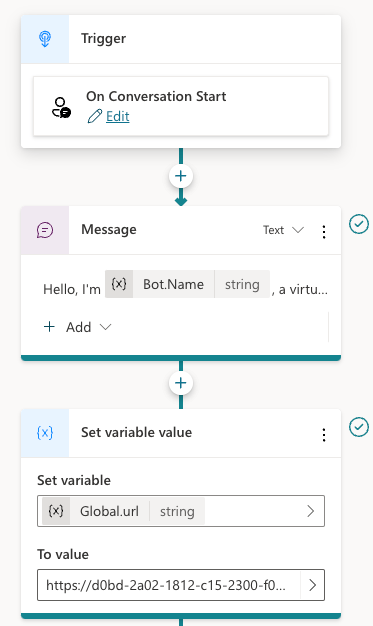

Below the set variable node, there are two other nodes:

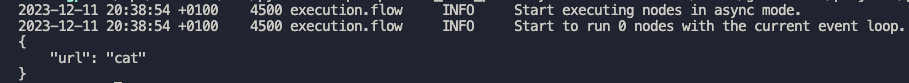

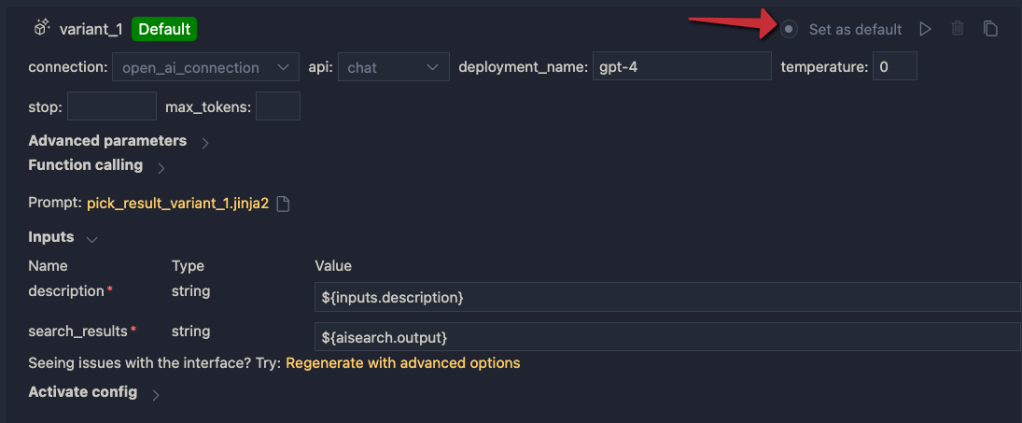

The HTTP Request node, unsurprisingly, can do HTTP requests. This is a built-in node in Copilot Studio. We call the /thread endpoint via the URL, which is the global url + “/thread” appended. The method is POST. In Headers and Body, you need to set the access_token header to the API key that matches the one from the code. There is no body to send here. When the request is successful, we save the thread ID to another global variable, global.thread_id. We need that variable is the /message calls later. The variable is of type record and holds the full JSON response from the /thread endpoint.

To finish the topic, we tell the user a new thread has started.

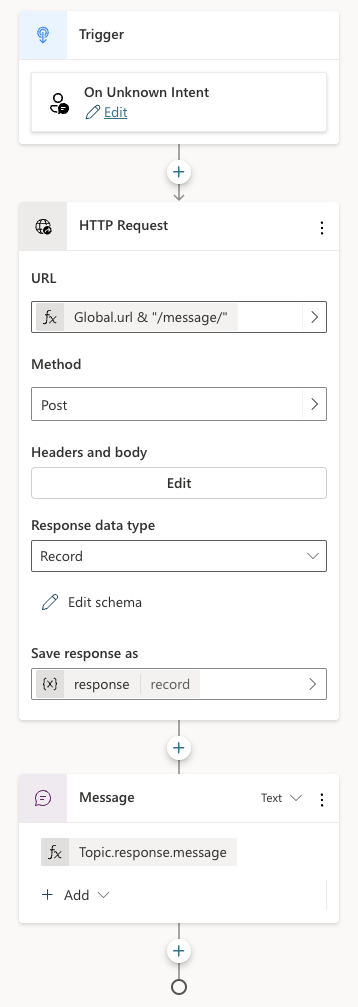

Now that we have a thread, how do we add a message to the thread? In the System Topics, I renamed the Fallback topic to Main intent. It is triggered when the intent is unknown, similar to how generative answers are used by default:

The topic is similar to the previous one:

Above, HTTP Request is used again, this time to call the /message endpoint. This time Headers and Body needs some more information. In addition to the access_token header, the request requires a JSON body:

The API expects JSON with two fields:

message: we capture what the user typed viaSystem.Activity.Textthread_id: stored inGlobal.thread_id.thread_id. TheGlobal.thread_idvariable is of type record (result from the/threadcall) and contains athread_idvalue. Great naming by yours truly here!

The last node in the topic simply takes the response record from the HTTP Request and sends the message field from that record back to the chat user.

You can now verify if the chat bot works from the Chat pane:

You can carry on a conversation with the assistant virtually indefinitely. As mentioned in previous posts, the assistants API tries to use up the model’s context window and only starts to trim messages from the thread when the context limit is reached.

If your assistant has tools and function calling, it’s possible it sends back images. The API does not account for that. Only text responses are retrieved.

Note: the API and bot configuration is just the bare minimum to get this to work; there is more work to do to make this fully functional, like showing image responses etc…

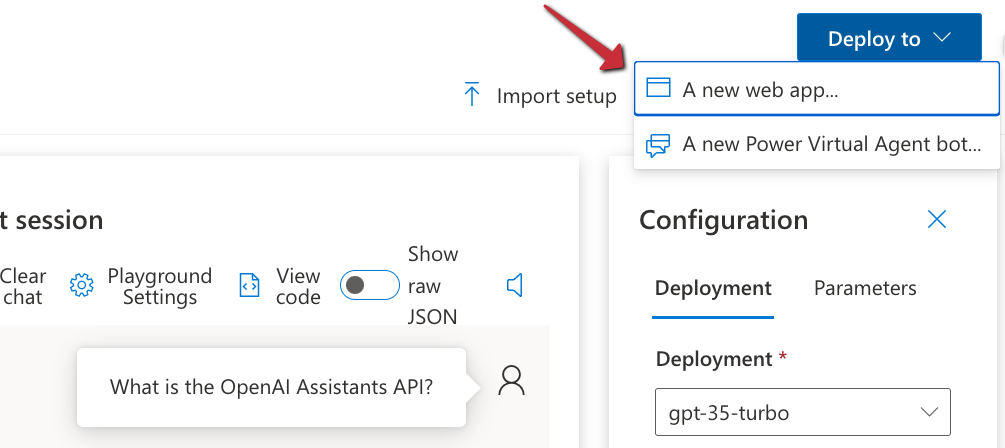

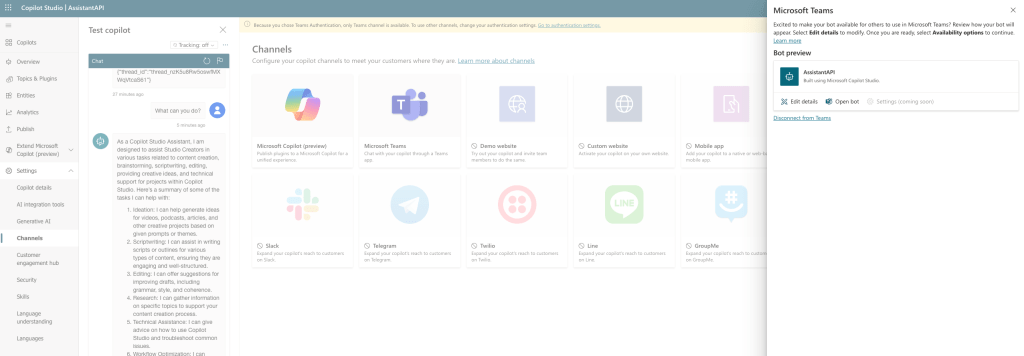

Adding a Teams channel

Copilot Studio bots can easily by tied to a channel. One of those channels is Teams. You can also do that with the Bot Framework SDK if you combine it with an Azure Bot resource. But it is easier with Copilot Studio.

Before you enable a channel, ensure your bot is published. Go to Publish (left pane) and click the Publish button.

Note: whenever you start a new ngrok session and update the URL in the bot, publish the bot again

Next, go to Settings and then Channels. I enabled the Teams channel:

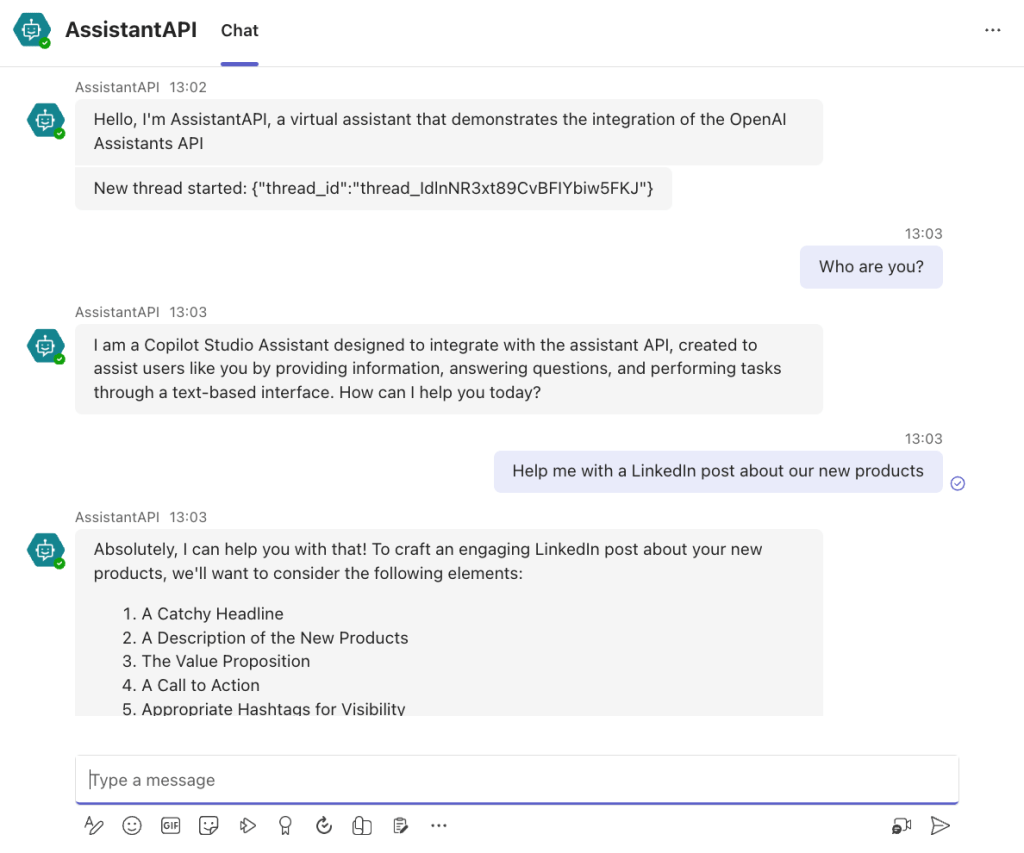

In the right pane, there’s a link to open the bot directly in Teams. It could be that does not work in your organisation but it does in mine:

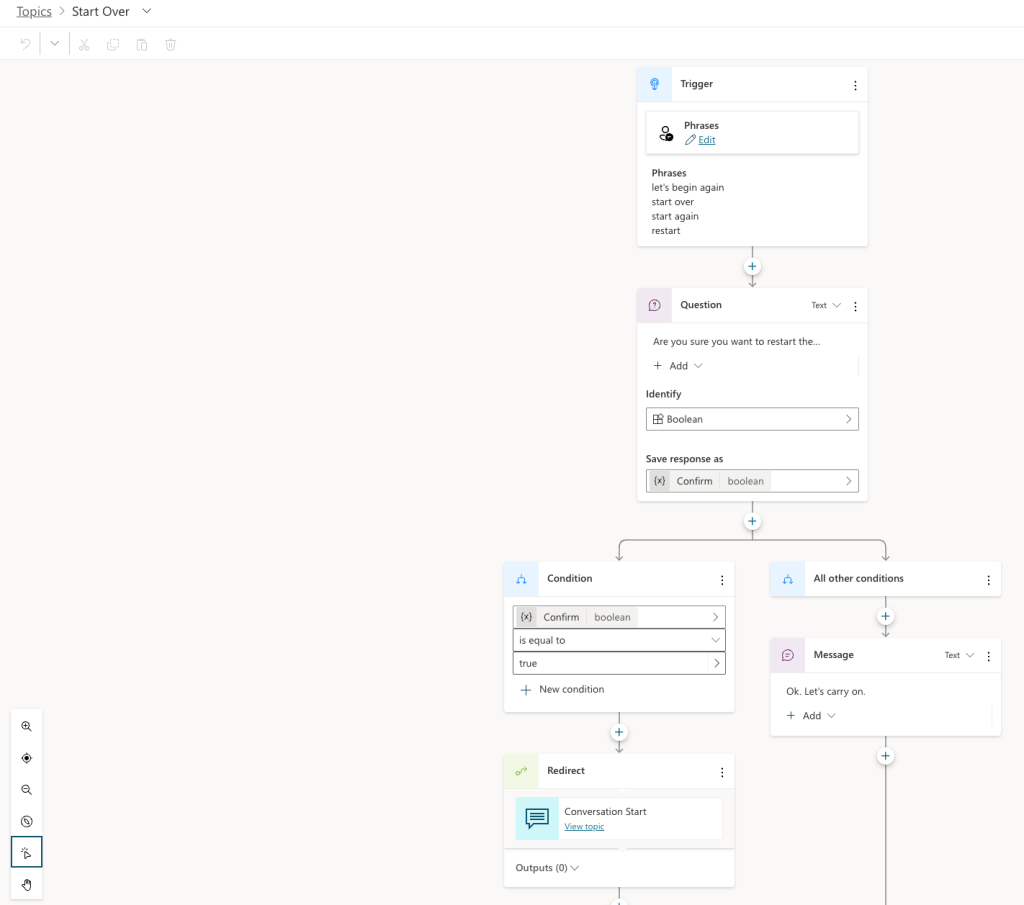

Note that it might be needed to restart the conversation if there is something wrong. By default, the chat bot has a Start Over topic. I modified that topic to redirect to Conversation Start. That results in the creation of a new thread:

The user can simple type something like Start Over. The bot would respond as follows:

Conclusion

If you want to use a low-code solution to build the front-end of an Azure OpenAI Assistant, using Copilot Studio in conjunction with the Assistants API is one way of achieving that.

Today, it does require some “pro-code” as the glue between both systems. I can foresee a future with tighter integration where this is just some UI configuration. I don’t know if the teams are working on this, but I surely would like to see it.