We often get the question to build an assistant based on the content of a website. These assistants often get implemented in one of two ways:

- Turn-based chat assistant: user can ask a question and follow-up questions

- Enhanced search: user asks a questions without the option to ask follow-up questions; this is often used to replace the built-in search functionalities of a website

In both cases, you have to make a decision about how to ground the LLM with your website content. There are several approaches:

- Use the website’s content management system (CMS): extract the content from the CMS, chunk it optimally and store it in a vector database like Azure AI Search

- Crawl the website and scrape the pages: the scraped content can then be chunked and vectorized just as in the first option

- Use a search engine: use Google or Bing to search for answers and optionally scrape pages in real time

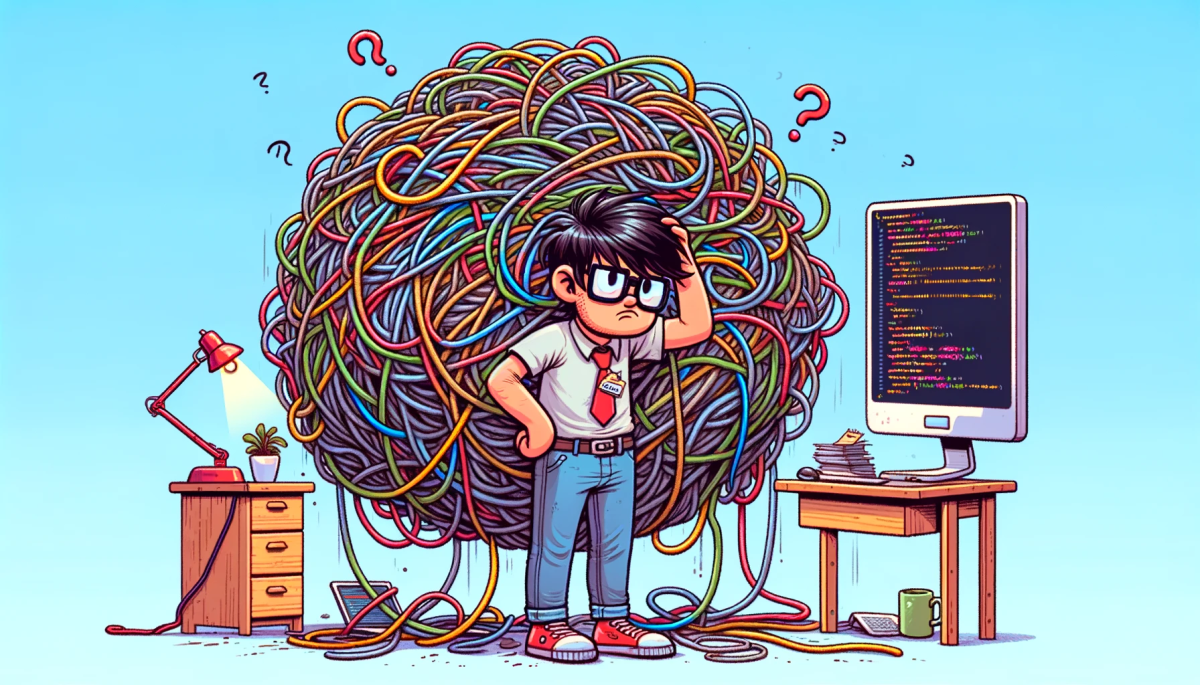

In the first two approaches, you need a pipeline and a vector database to properly store and update your vectorized chunks. It is often underestimated that creating and maintaining such a pipeline is a complex matter. You have to add new content, update existing content and remove content that is not required anymore. You need to run that pipeline on a schedule or based on user demand. You have to add proper logging to know when it goes wrong etc… It is a never ending story.

The search engine approach is much simpler and might be the easiest to implement, depending on your use case. Let’s take a look at how this works. We will look at two approaches:

- Custom: call the Bing API from your code and use the output in your prompt; you have full control

- Azure AI Agent Service: use the Bing grounding tool that is part of the knowledge tools of the agent service; the grounding tool is somewhat of a black box which means less control but easier to use

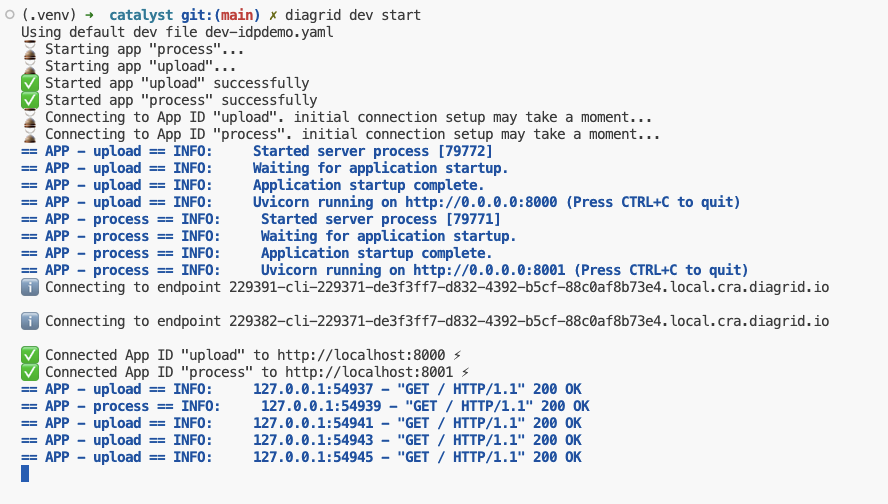

Calling the Bing API from your code

To use the Bing API and make it work on a subset of websites, you should use a Bing Custom Search resource in Azure:

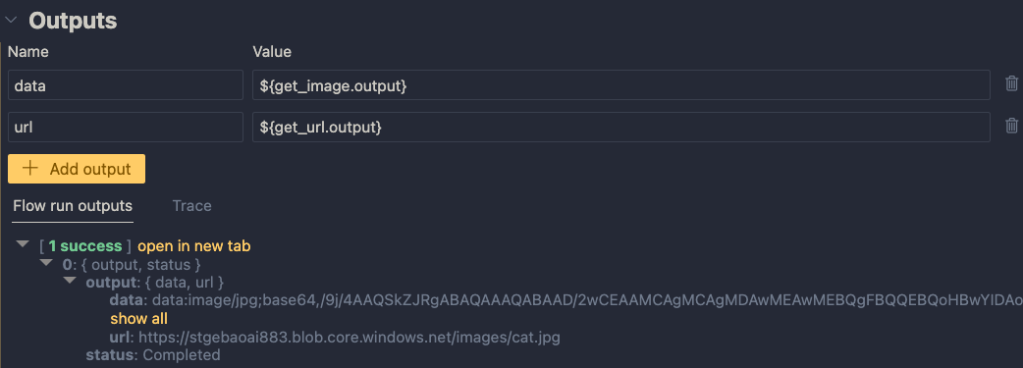

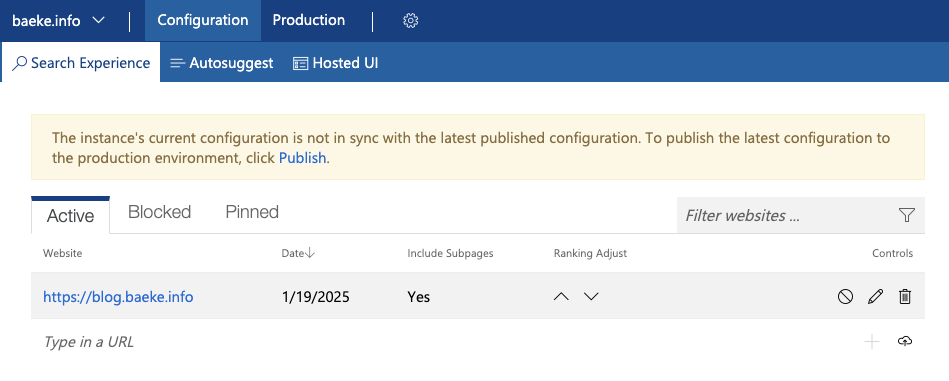

To customize the search, you can go to the instructions on Microsoft Learn. They explain how to go to the Bing custom search portal to create a custom search instance. The screenshot below shows a custom instance named baeke.info:

This custom instance contains my blog because I want the custom search resource to only return results from my blog and not any other website.

When you create a custom instance, you get a Custom Configuration ID you can provide to the search API. Ensure to publish the custom instance before using it in your code.

To search using a custom configuration ID, you can use the following code. I used the REST API below:

bing_endpoint = 'https://api.bing.microsoft.com/v7.0/custom/search'

headers = {

'Ocp-Apim-Subscription-Key': bing_subscription_key

}

params = {

'q': query,

'customconfig': 'YOUR_CUSTOM_CONFIG_KEY',

'mkt': 'en-US'

}

response = requests.get(bing_endpoint, headers=headers, params=params)

web_data = response.json()The bing_subscription_keycan be found in your Bing Custom Search resource in Azure. The query q was provided by the user. The customconfig field is the custom configuration ID of the custom search instance.

The response, web_data, should contain a webPages field that has a value field. The value field is an array of search results. In each result is a url and a snippet field. The snippet should be relevant to the user’s query and can be used as grounding information. Below is the first result for the query “What is the OpenAI Assistants API” from my blog:

{

"id": "https://api.bing.microsoft.com/api/v7/#WebPages.0",

"name": "Using tools with the Azure OpenAI Assistants API – baeke.info",

"url": "https://atomic-temporary-16150886.wpcomstaging.com/2024/02/09/using-tools-with-the-azure-openai-assistants-api/",

"urlPingSuffix": "DevEx,5113.1",

"datePublished": "2024-02-09T00:00:00.0000000",

"datePublishedDisplayText": "9 Feb 2024",

"isFamilyFriendly": true,

"displayUrl": "https://atomic-temporary-16150886.wpcomstaging.com/2024/02/09/using-tools-with-the-azure-openai-assistants-api",

"snippet": "In this post, we will provide the assistant with custom tools. These custom tools use the function calling features of more recent GPT models. As a result, these custom tools are called functions in the Assistants API. What’s in a name right? There are a couple of steps you need to take for this to work: Create an assistant and give it a name ...",

"deepLinks": [],

"dateLastCrawled": "2025-01-14T18:08:00.0000000Z",

"openGraphImage": {

"contentUrl": "https://i0.wp.com/atomic-temporary-16150886.wpcomstaging.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/dallc2b7e-2024-02-09-16.49.38-visualize-a-cozy-and-inviting-office-space-where-a-charming-ai-assistant-is-the-heart-of-interaction-taking-the-form-of-a-small-adorable-robot-with-.webp?resize=1200%2C1024&ssl=1",

"width": 0,

"height": 0

},

"fixedPosition": false,

"language": "en",

"isNavigational": true,

"noCache": true,

"siteName": "baeke.info"

}Above, the first result is actually not the most relevant. However, the query returns 10 results by default and all 10 snippets can be provided as context to your LLM. Typically, a default search with 10 results takes under a second to complete.

Of course, the snippets are relatively short. They are snippets after all. If the snippets do not provide enough context, you can scrape one or more pages from the results and add that to your context.

To scrape web pages, you have several options:

- Use a simple HTTP request: this if not sufficient to retrieve content from dynamic websites that use Javascript to load content; if the website is fully static, you can use this approach

- Use scraping services: scraping services like Jina Reader (https://jina.ai/) or Firecrawl (https://www.firecrawl.dev/); although they have a free tier, most production applications will require paying extra for these services

- Use open source solutions: there are many available solutions; Crawl4AI (https://crawl4ai.com/mkdocs/) is a service with many options; it is a bit harder to use and there are lots of dependencies because the crawler relies on headless browsers and tools like Playwright.

Below is a basic class that uses Jina to scrape URLs in parallel:

import os

import asyncio

import logging

import aiohttp

from typing import List, Dict, Any

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv()

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO, format='%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

class ParallelCrawler:

def __init__(self, urls: List[str], max_concurrent: int = 3, api_key: str = None):

logger.info(f"Initializing crawler with {len(urls)} URLs and max_concurrent={max_concurrent}")

self.urls = urls

self.max_concurrent = max_concurrent

self.api_key = api_key or os.environ.get('JINA_API_KEY')

self.base_url = 'https://r.jina.ai/'

async def fetch_url(self, session: aiohttp.ClientSession, url: str) -> Dict[str, Any]:

jina_url = f"{self.base_url}{url}"

logger.debug(f"Fetching URL: {jina_url}")

headers = {

"Accept": "application/json",

"Authorization": f"Bearer {self.api_key}",

"X-Retain-Images": "none",

"X-Return-Format": "markdown"

}

try:

async with session.get(jina_url, headers=headers) as response:

logger.info(f"Response status for {url}: {response.status}")

if response.status != 200:

logger.error(f"Error fetching {url}: HTTP {response.status}")

return None

return await response.json()

except Exception as e:

logger.error(f"Exception while fetching {url}: {str(e)}")

raise

async def crawl(self):

logger.info(f"Starting parallel crawling of {len(self.urls)} URLs")

all_results = []

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = []

for url in self.urls:

logger.debug(f"Creating task for URL: {url}")

tasks.append(self.fetch_url(session, url))

logger.info(f"Executing {len(tasks)} tasks concurrently")

responses = await asyncio.gather(*tasks, return_exceptions=True)

for i, response in enumerate(responses):

if isinstance(response, Exception):

logger.error(f"Failed to process {self.urls[i]}: {response}")

continue

if response and response.get('data'):

logger.info(f"Successfully processed {self.urls[i]}")

all_results.append(response['data']['content'])

else:

logger.warning(f"No data returned for {self.urls[i]}")

logger.info(f"Crawling complete. Processed {len(all_results)} URLs successfully")

return all_results

def run(self):

logger.info("Starting crawler run")

result = asyncio.run(self.crawl())

logger.info("Crawler run completed")

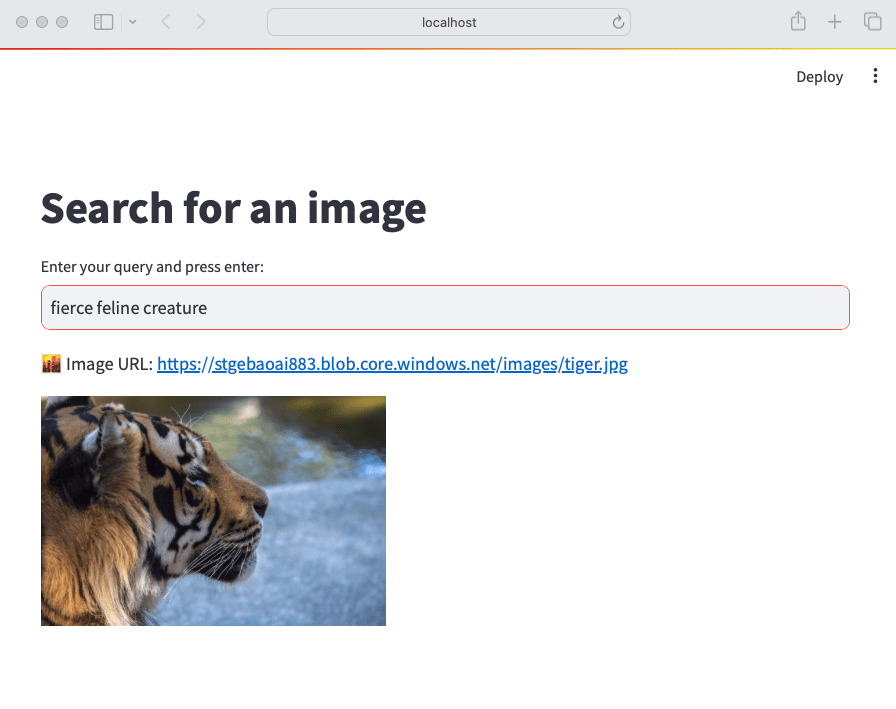

return resultWith the combination of Bing snippets and, optionally, the full content from the top articles, you can create a prompt with the original user query and the context from Bing and scraping. Below is an example web app, that uses these features:

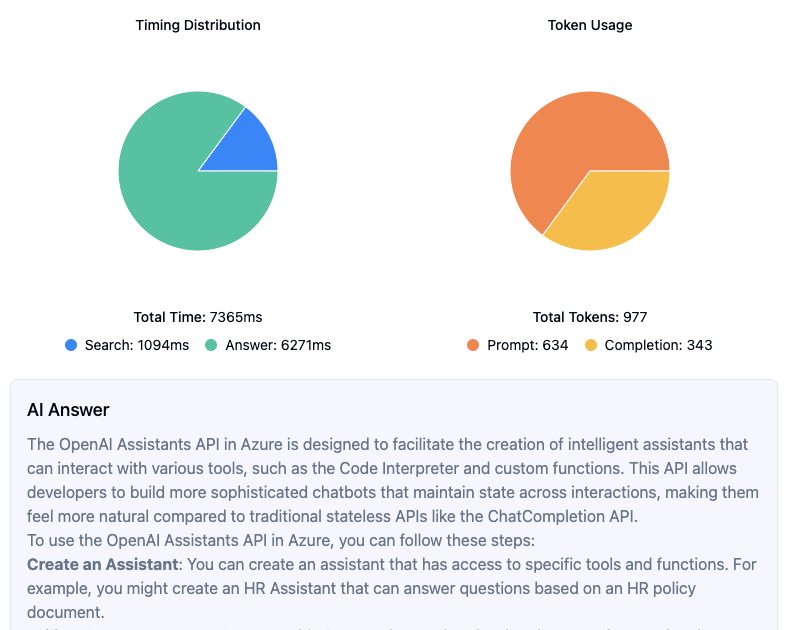

Above, fetch mode was enabled to add the full content of the first three Bing results to the prompt. The Bing search takes about a second. The time to answer, which includes scraping and an Azure OpenAI chat completion, takes quite a bit of time. Most of the time is consumed by the chat completion. Although you could optimize the scraper by introducing caching, that will only result in modest time savings.

The prompt is rather large because it contains markdown for three of my blog posts. If we limit the search to Bing only, the result is as follows:

In this case, the answer is a bit more generic. The snippets contain information relevant to the query of the user but they do not contain enough information. This is especially true for more complex questions. The upside is faster speed and much less token consumption.

To keep the amount of tokens to a minimum, you could chunk the scraped websites in real time, filter out the relevant chunks using similarity metrics and only feed those chunks to the prompt. You can use the snippet to find relevant chunks or the user’s original query.

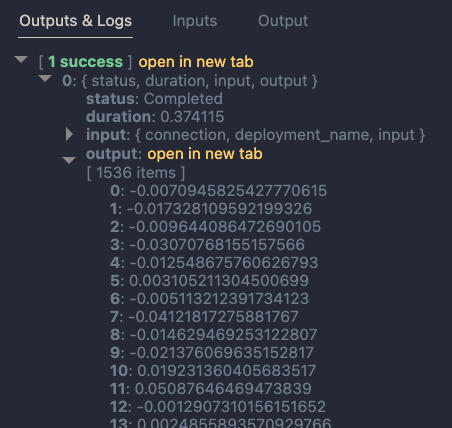

To really speed things up, you could implement prompt caching. The screenshot below shows the cache in action:

In this case, we store previous questions and answers in Redis. When a new question comes in, we check if there are similar questions based on vector similarity. When the similarity score is above 0.95, a threshold we configure, we use the cache. Otherwise, we search, scrape and use OpenAI as before. Needless to say that this is very fast.

You need to write quite some code to implement the searching, scraping and caching features. The web application above uses this code via a web API you have to write and host yourself. Depending on your needs, there might be an easier solution by using the Azure AI Agent Service with built-in Bing grounding.

Using the Azure AI Agent Service with Bing Grounding

The new Azure AI Agent Service supports grounding with Bing Search out of the box as documented here: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/ai-services/agents/how-to/tools/bing-grounding.

When you ask the agent a question by adding a message to a thread and running the thread, the agent will automatically use Bing to ground its answer.

It works by adding a Bing connection to an Azure AI Foundry project and providing the grounding tool to the agent. Take a look at the sample code below:

import os

from azure.ai.projects import AIProjectClient

from azure.identity import DefaultAzureCredential

from azure.ai.projects.models import BingGroundingTool

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv()

project_client = AIProjectClient.from_connection_string(

credential=DefaultAzureCredential(),

conn_str=os.environ["PROJECT_CONNECTION_STRING"],

)

bing_connection = project_client.connections.get(

connection_name=os.environ["BING_CONNECTION_NAME"]

)

conn_id = bing_connection.id

print(conn_id)

# Initialize agent bing tool and add the connection id

bing = BingGroundingTool(connection_id=conn_id)

# Create agent with the bing tool and process assistant run

with project_client:

agent = project_client.agents.create_agent(

model="gpt-4o-global",

name="my-assistant",

instructions="You are a helpful assistant",

tools=bing.definitions,

headers={"x-ms-enable-preview": "true"}

)Above, we connect to an Azure AI Foundry project with Entra ID. Next, we grab the connection identified by the value of the BING_CONNECTION_NAME environment variable. With the id of the connection, we can create the BingGroundingTool and add it to the tools property of our agent.

The advantage of this approach is that it is easy to use and configure. However, there are several drawbacks:

- The tool does not surface all the URLs it found so you cannot display them nicely in a client application

- It is currently not possible to provide a custom configuration key to search a subset of sites (e.g., only https://baeke.info for instance)

At the time of writing, the Azure AI Agent Service SDK was in preview so some or all of the drawbacks might be solved before or at general availability.

Sample implementation

You can find an easy to use example in this gist: https://gist.github.com/gbaeke/97afb88da56d59e1b6ca460653fc8700. To make it work, do the following:

- In a new folder, save the script as

app.py - Create a

.envfile with two environment variables:OPENAI_API_KEY,BING_API_KEY - Install packages:

pip install fastapi python-dotenv uvicorn requests beautifulsoup4 openai sentence-transformers scikit-learn numpy - Run the api with

python app.py

The example uses a simple chunking technique in addition to the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 SentenceTranformer to vectorize chunks and return the top 3 results to include in the OpenAI prompt’s context. To scrape web pages, we use a simple HTTP GET with BeautifulSoup. As discussed above, that will not yield good results with dynamic web pages. Most web pages will be fine though.

Conclusion

When you want to create an AI assistant or AI-based search feature based on a website using the site’s content, using Bing Search for grounding is one of the options. We discussed two approaches:

- Fully custom code with the Bing custom search API

- Azure AI Agents with the Bing grounding service

The first approach gives you full control over how you perform the search and process the results. You can rely on just the snippets provided by Bing or add the full content of the top URLs to your prompt with scraping. To improve response times you can add scrape caching or prompt caching. Prompt caching will provide you with almost instantaneous results when the prompt and answer was previously cached. You do not need to implement a pipeline to keep your vector database up-to-date.

Although built-in Bing grounding with the Azure AI Agent service is much easier, it has some limitations for the use case that I described. However, if you need to add general grounding to augment LLM responses, the Bing Grounding tool is definitely the one to go for. And although not discussed in this article, if you can use Copilot Studio, Bing grounding based on specific websites is available and is even easier to implement with just a few clicks!