If you have ever created an application that makes calls to Azure OpenAI models, you know there are limits to the amount of calls you can make per minute. Take a look at the settings of a GPT model below:

Above, the tokens per minute (TPM) rate limit is set to 60 000 tokens. This translates to about 360 requests per minute. When you exceed these limits, you get 429 Too Many Requests errors.

There are many ways to deal with these limits. A few of the main ones are listed below:

- You can ask for a PAYGO quota increase: remember that high quotas do not necessarily lead to consistent lower-latency responses

- You can use PTUs (provisioned throughput units): highly recommended if you want consistently quick responses with the lowest latency. Don’t we all? 😉

- Your application can use retries with backoffs. Note that OpenAI libraries use automatic retries by default. For Python, it is set to two but that is configurable.

- You can use multiple Azure OpenAI instances and load balance between them

In this post, we will take a look at implementing load balancing between OpenAI resources with an open source solution called LiteLLM. Note that, in Azure, you can also use Azure API Management. One example is discussed here. Use it if you must but know it is not simple to configure.

A look at LiteLLM

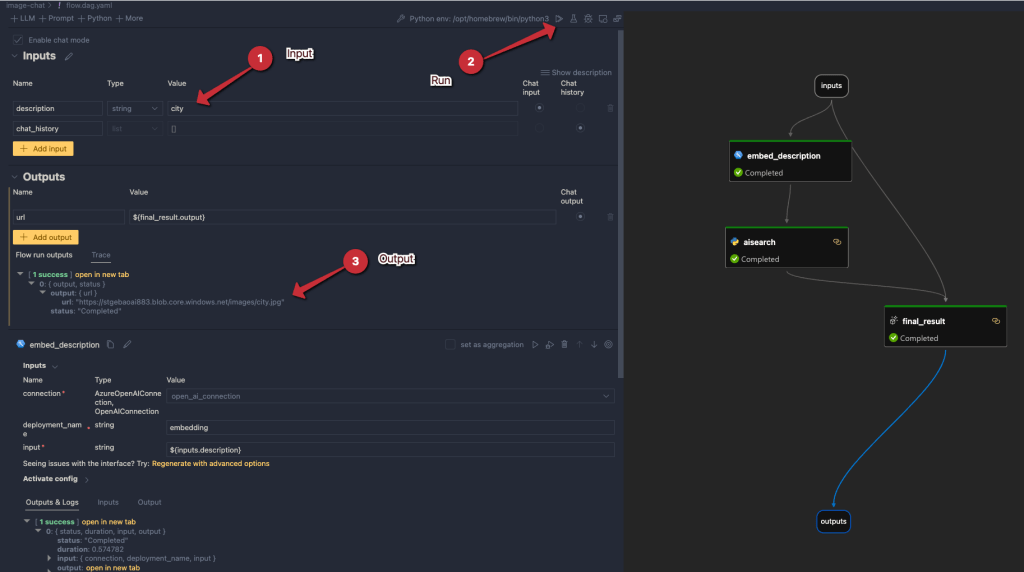

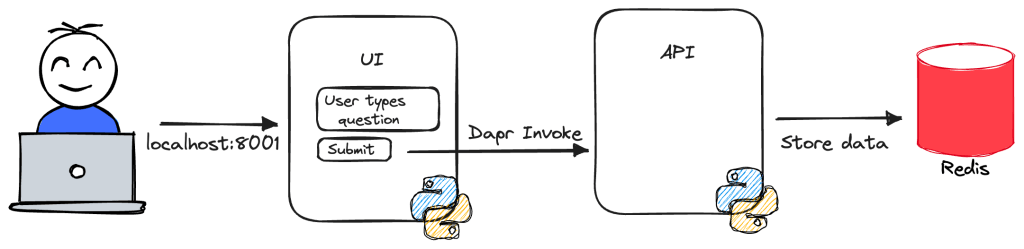

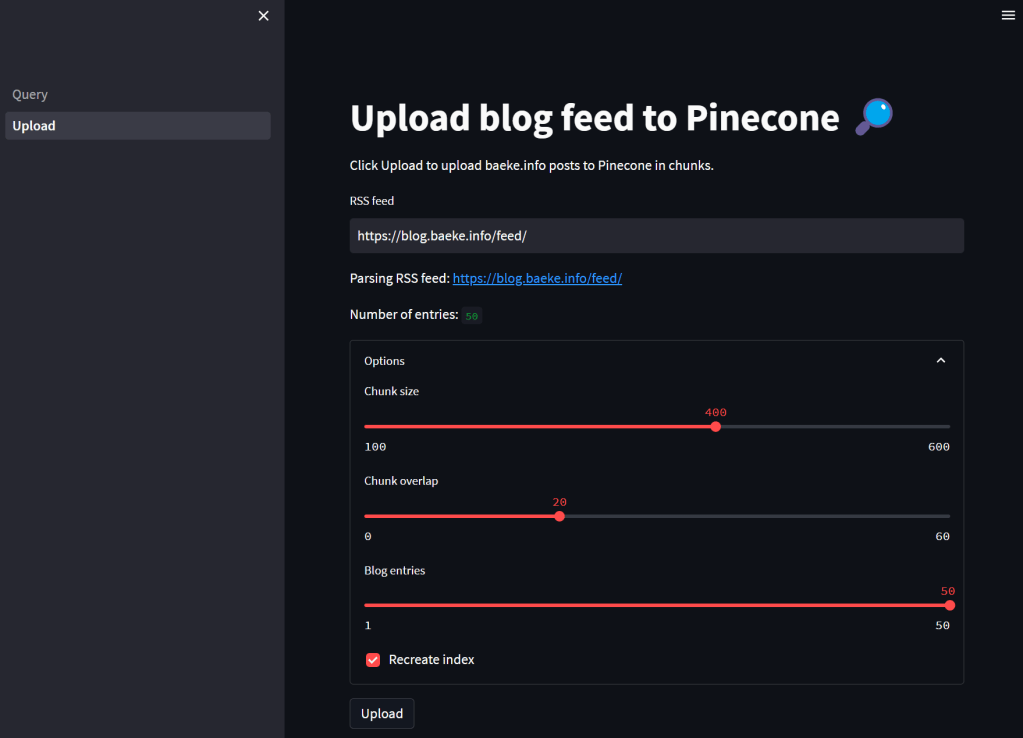

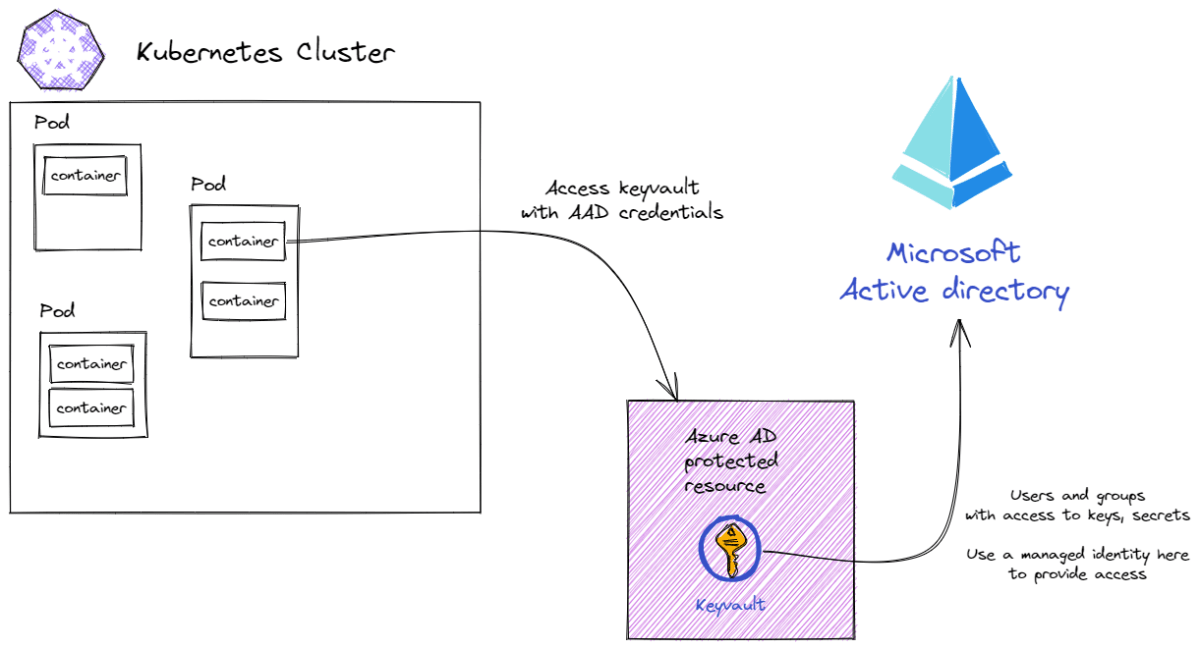

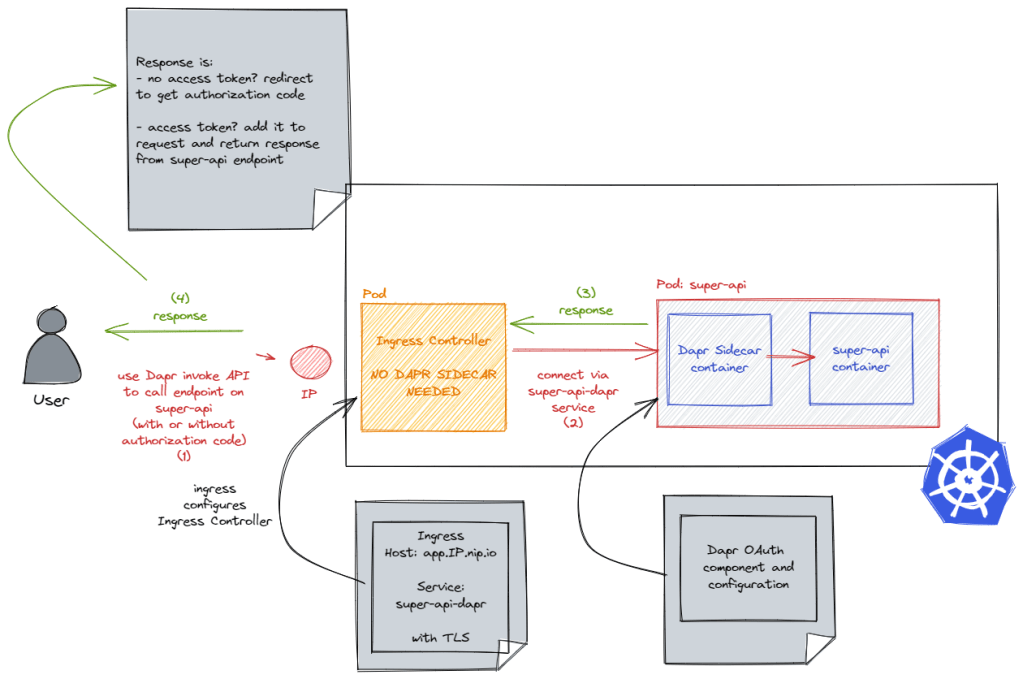

LiteLLM has many features. In this post, I will be implementing it as a standalone proxy, running as a container in Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS). The proxy is part of a larger application illustrated in the diagram below:

The application above has an upload service that allows users to upload a PDF or other supported document. After storing the document in an Azure Storage Account container, the upload service sends a message to an Azure Service Bus topic. The process service uses those messages to process each file. One part of the process is the use of Azure OpenAI to extract fields from the document. For example, a supplier, document number or anything else.

To support the processing of many documents, multiple Azure OpenAI resources are used: one in France and one in Sweden. Both regions have the gpt-4-turbo model that we require.

The process service uses the Python OpenAI library in combination with the instructor library. Instructor is great for getting structured output from documents based on Pydantic classes. Below is a snippet of code:

from openai import OpenAI

import instructor

client = instructor.from_openai(OpenAI(

base_url=azure_openai_endpoint,

api_key=azure_openai_key

))The only thing we need to do is to set the base_url to the LiteLLM proxy. The api_key is configurable. By default it is empty but you can configure a master key or even virtual keys for different teams and report on the use of these keys. More about that later.

The key point here is that LiteLLM is a transparent proxy that fully supports the OpenAI API. Your code does not have to change. The actual LLM does not have to be an OpenAI LLM. It can be Gemini, Claude and many others.

Let’s take a look at deploying the proxy in AKS.

Deploying LiteLLM on Kubernetes

Before deploying LiteLLM, we need to configure it via a config file. In true Kubernetes style, let’s do that with a ConfigMap:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: litellm-config-file

data:

config.yaml: |

model_list:

- model_name: gpt-4-preview

litellm_params:

model: azure/gpt-4-preview

api_base: os.environ/SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT

api_key: os.environ/SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY

rpm: 300

- model_name: gpt-4-preview

litellm_params:

model: azure/gpt-4-preview

api_base: os.environ/FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT

api_key: os.environ/FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY

rpm: 360

router_settings:

routing_strategy: least-busy

num_retries: 2

timeout: 60

redis_host: redis

redis_password: os.environ/REDIS_PASSWORD

redis_port: 6379

general_settings:

master_key: os.environ/MASTER_KEYThe configuration contains a list of models. Above, there are two models with the same name: gpt-4-preview. Each model points to a deployed model in Azure with the same name (can be different) and its own API base and key. For example, the first model uses an API base and API key for my instance in Sweden. However, by using os.environ/ and appending an environment variable, we can tell LiteLLM to use an environment variable. Of course, that means we have to set these environment variables in the LiteLLM container. We will do that later.

When the code in the process service uses the gpt-4-preview model via the proxy, the proxy will perform load balancing based on the router settings.

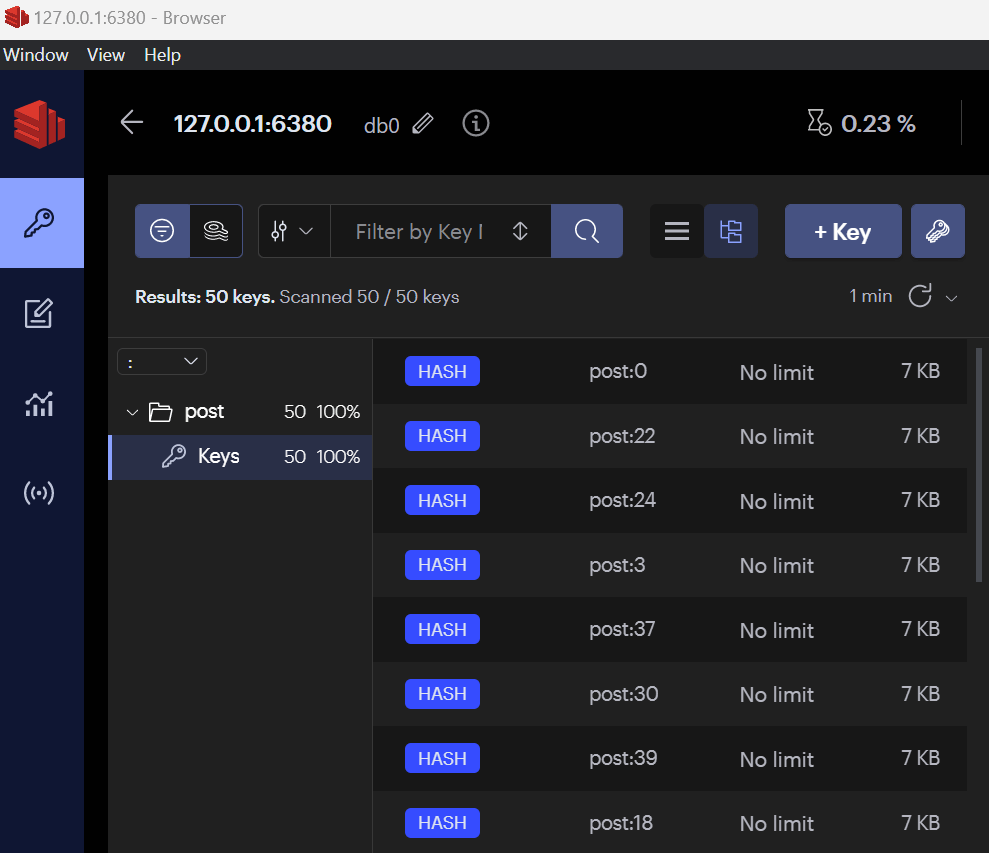

To spin up more than one instance of LiteLLM, a Redis instance is required. Redis is used to share information between the instances to make routing decisions. The routing strategy is set to least-busy.

Note that retries is set to 2. You can turn off retries in your code and let the proxy handle this for you.

To support mounting the secrets as environment variables, I use a .env file in combination with a secretGenerator in Kustomize:

STORAGE_CONNECTION_STRING=<placeholder for storage connection string>

CONTAINER=<placeholder for container name>

AZURE_AI_ENDPOINT=<placeholder for Azure AI endpoint>

AZURE_AI_KEY=<placeholder for Azure AI key>

AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT=<placeholder for Azure OpenAI endpoint>

AZURE_OPENAI_KEY=<placeholder for Azure OpenAI key>

LLM_LITE_SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT=<placeholder for LLM Lite SWE Azure OpenAI endpoint>

LLM_LITE_SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY=<placeholder for LLM Lite SWE Azure OpenAI key>

LLM_LITE_FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT=<placeholder for LLM Lite FRA Azure OpenAI endpoint>

LLM_LITE_FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY=<placeholder for LLM Lite FRA Azure OpenAI key>

TOPIC_KEY=<placeholder for topic key>

TOPIC_ENDPOINT=<placeholder for topic endpoint>

PUBSUB_NAME=<placeholder for pubsub name>

TOPIC_NAME=<placeholder for topic name>

SB_CONNECTION_STRING=<placeholder for Service Bus connection string>

REDIS_PASSWORD=<placeholder for Redis password>

MASTER_KEY=<placeholder for Cosmos DB master key>

POSTGRES_DB_URL=postgresql://USER:PASSWORD@SERVERNAME-pg.postgres.database.azure.com:5432/postgresThere are many secrets here. Some are for LiteLLM, although weirdly prefixed with LLM_LITE instead. I do that sometimes! The others are to support the upload and process services.

To get these values into secrets, I use the following kustomization.yaml:

apiVersion: kustomize.config.k8s.io/v1beta1

kind: Kustomization

namespace: inv-demo

resources:

- namespace.yaml

- pubsub.yaml

- upload.yaml

- process.yaml

- llmproxy.yaml

- redis.yaml

secretGenerator:

- name: invoices-secrets

envs:

- .env

generatorOptions:

disableNameSuffixHash: trueThe secretGenerator will create a secret called invoices-secrets in the inv-demo namespace. We can reference the secrets in the LiteLLM Kubernetes deployment:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: litellm-deployment

labels:

app: litellm

spec:

replicas: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app: litellm

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: litellm

spec:

containers:

- name: litellm

image: ghcr.io/berriai/litellm:main-latest

args:

- "--config"

- "/app/proxy_server_config.yaml"

ports:

- containerPort: 4000

volumeMounts:

- name: config-volume

mountPath: /app/proxy_server_config.yaml

subPath: config.yaml

env:

- name: SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: invoices-secrets

key: LLM_LITE_SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT

- name: SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: invoices-secrets

key: LLM_LITE_SWE_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY

- name: FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: invoices-secrets

key: LLM_LITE_FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_ENDPOINT

- name: FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: invoices-secrets

key: LLM_LITE_FRA_AZURE_OPENAI_KEY

- name: MASTER_KEY

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: invoices-secrets

key: MASTER_KEY

- name: DATABASE_URL

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: invoices-secrets

key: POSTGRES_DB_URL

volumes:

- name: config-volume

configMap:

name: litellm-config-fileThe ConfigMap content is mounted as /app/proxy_server_config.yaml. You need to specify the config file via the --config parameter, supplied in args.

Next, we simply mount all the environment variables that we need. The LiteLLM ConfigMap uses several of those via the os.environ references. There is also a DATABASE_URL that is not mentioned in the ConfigMap. The URL points to a PostgreSQL instance in Azure where information is kept to support the LiteLLM dashboard and other settings. If you do not want the dashboard feature, you can omit the database URL.

There’s one last thing: the process service needs to connect to LiteLLM via Kubernetes internal networking. Of course, that means we need a service:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: litellm-service

spec:

selector:

app: litellm

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

targetPort: 4000

type: ClusterIPWith this service definition, the process service can set the OpenAI base URL as http://litellm-service to route all requests to the proxy via its internal IP address.

As you can probably tell from the kustomization.yaml file, the ConfigMap, Deployment and Service are in llmproxy.yaml. The other YAML files do the following:

- namespace.yaml: creates the

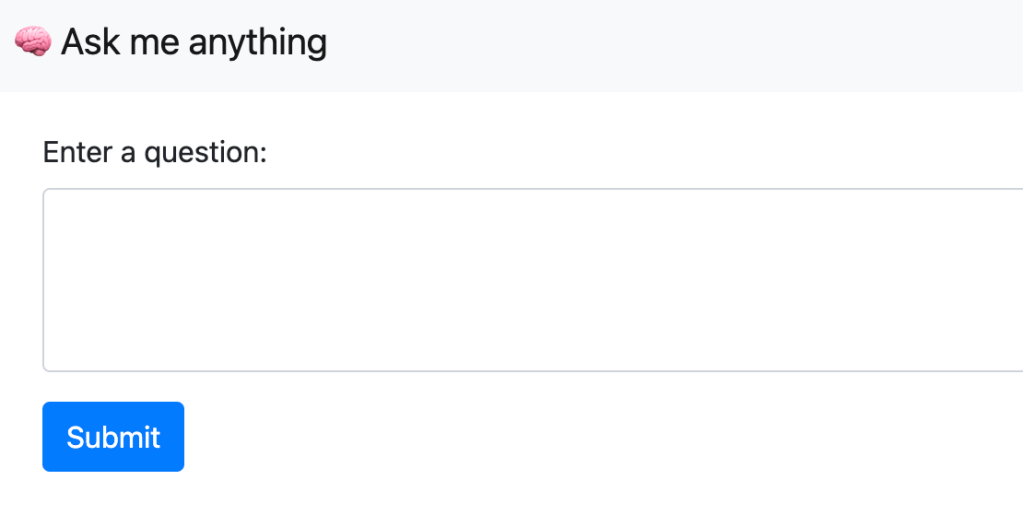

inv-demonamespace - upload.yaml: deploys the upload service (written in Python and uses FastAPI, 1 replica))

- process.yaml: deploys the process service (written in Python as a Dapr grpc service, 2 replicas)

- pubsub.yaml: creates a Dapr pubsub component that uses Azure Service Bus

- redis.yaml: creates a standalone Redis instance to support multiple replicas of the LiteLLM proxy

To deploy all of the above, you just need to run the command below:

kubectl apply -k .

⚠️ Although this can be used in production, several shortcuts are taken. One thing that would be different is secrets management. Secrets would be in a Key Vault and made available to applications via the Secret Store CSI driver or other solutions.

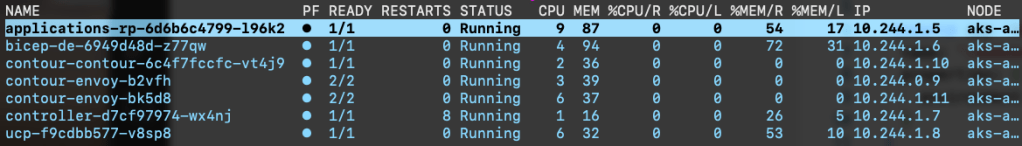

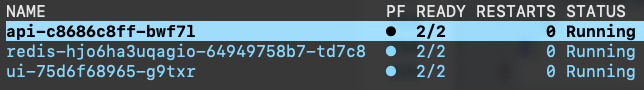

With everything deployed, I see the following in k9s:

As a side note, I also use Diagrid to provide insights about the use of Dapr on the cluster:

Dapr is only used between process and upload. The other services do not use Dapr and, as a result, are not visible here. The above is from Diagrid Conductor Free. As I said…. total side note! 🤷♂️

Back to the main topic…

The proxy in action

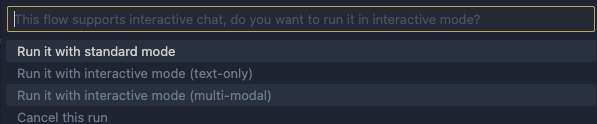

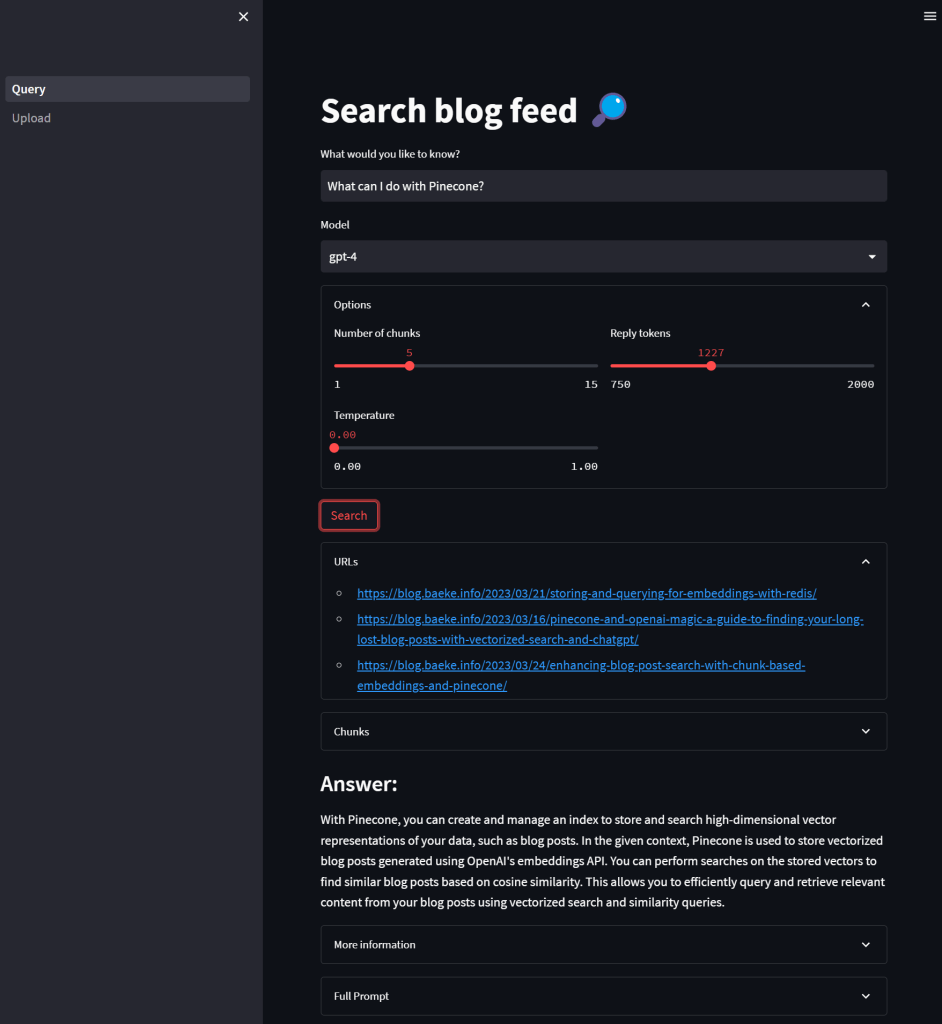

Let’s see if the proxy uses both Azure OpenAI instances. The dashboard below presents a view of the metrics after processing several documents:

It’s clear that the proxy uses both resources. Remember that this is the least-busy routing option. It picks the deployment with the least number of ongoing calls. Both these instances are only used by the process service so the expectation is a more or less even distribution.

LiteLLM Dashboard

If you configured authentication in combination with providing a URL to a PostGreSQL database, you can access the dashboard. To see the dashboard in action without deploying it, see https://litellm.vercel.app/docs/proxy/demo.

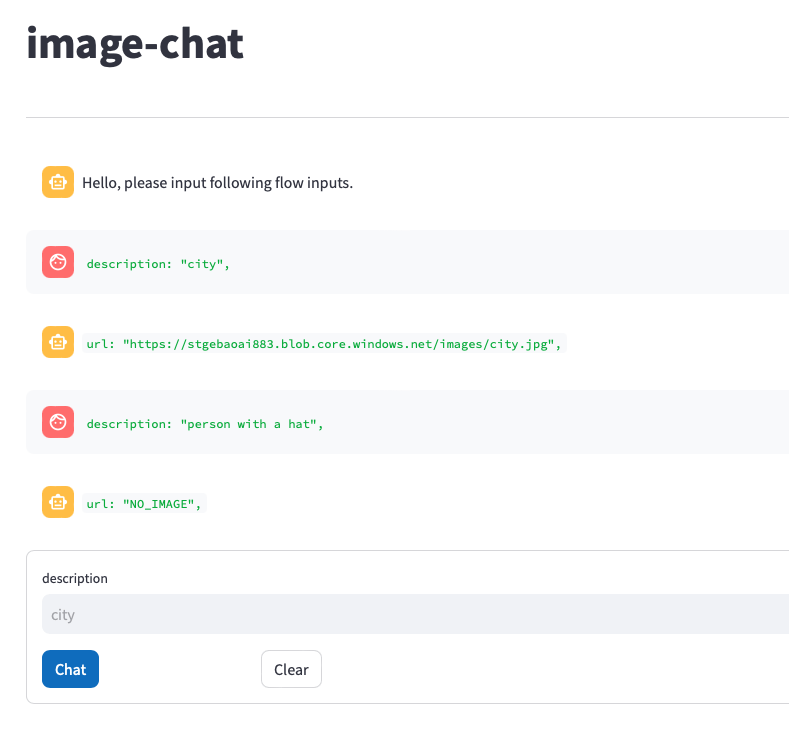

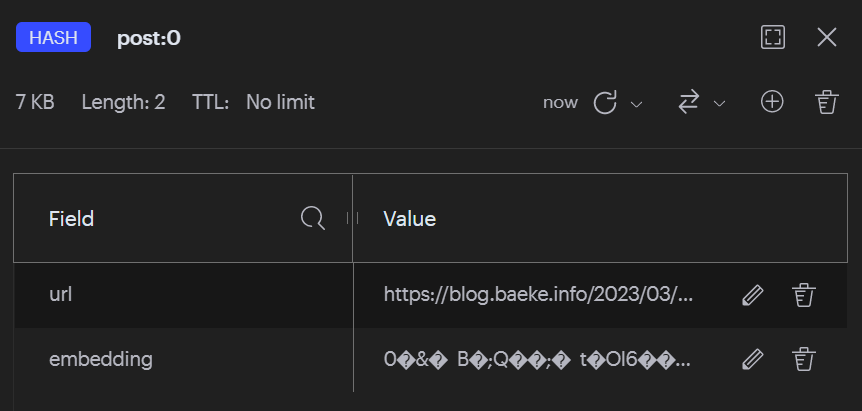

One of the things you can do is creating teams. Below, you see a team called dev which has access to only the gpt-4-preview model with unlimited TPM and RPM:

In addition to the team, a virtual key is created and assigned to the team. This virtual key starts with sk- and is used as the OpenAI API key in the process service:

We can now report on the use of OpenAI by the dev team:

Above, there’s a small section that’s unassigned because I used LiteLLM without a key and a master key before switching to a team-based key.

The idea here is that you can deploy the LiteLLM proxy centrally and hand out virtual keys to teams so they can all access their models via the proxy. We have not tested this in a production setting yet but it is certainly something worth exploring.

Conclusion

I have only scratched the surface of LiteLLM here but my experience with it so far is pretty good. If you want to deploy it as a central proxy server that developers can use to access models, deployment to Kubernetes and other environments with the container image is straightforward.

In this post I used Kubernetes but that is not required. It runs in Container Apps and other container runtimes as well. In fact, you do not need to run it in a container at all. It also works as a standalone application or can be used directly in your Python apps.

There is much more to explore but for now, if you need a transparent OpenAI-based proxy that works with many different models, take a look at LiteLLM.