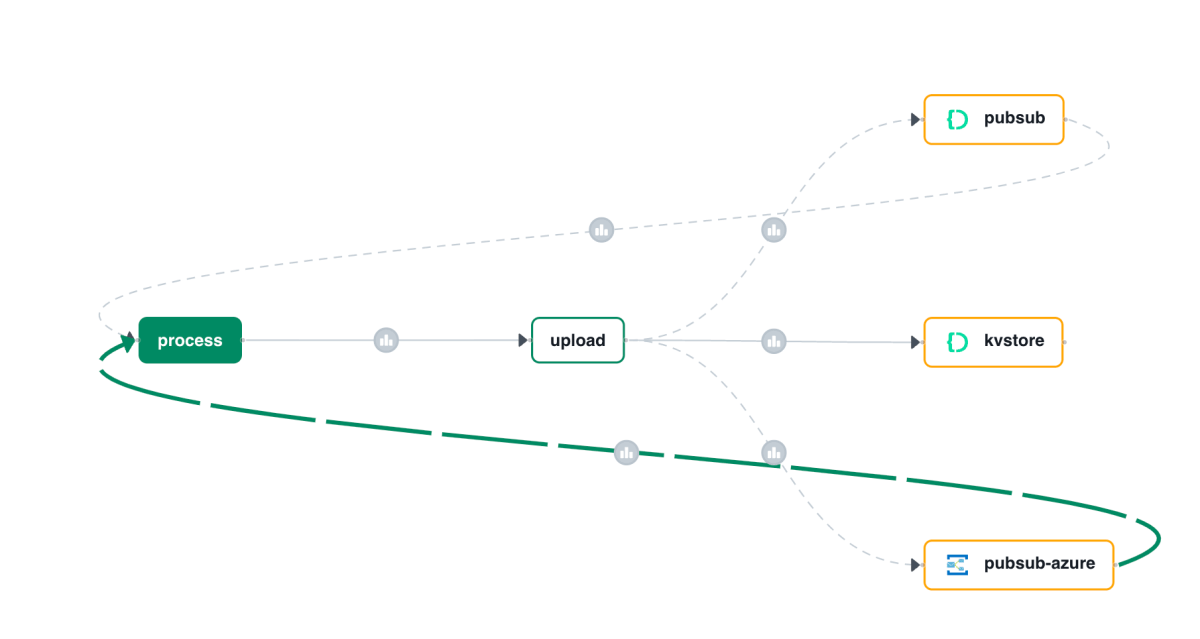

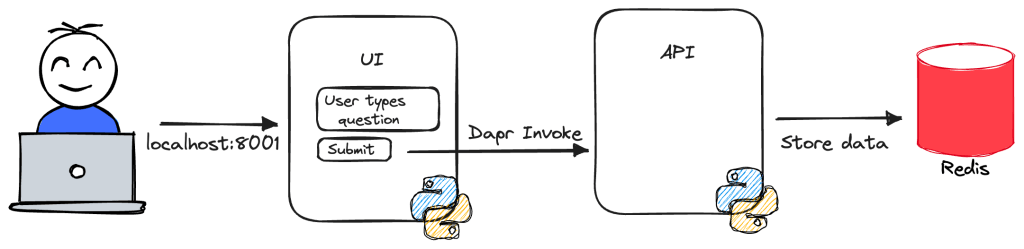

In a previous post we created a simple A2A agent that uses synchronous message exchange. An A2A client sends a message and the A2A server, via the Agent Executor, responds with a message.

But what if you have a longer running task to perform and you want to inform the client that the task in ongoing? In that case, you can enable streaming on the A2A server and use a task that streams updates and the final result to the client.

The sequence diagram illustrates the flow of messages. It is based on the streaming example in the A2A specification.

In this case, the A2A client needs to perform a streaming request which is sent to the /message/stream endpoint of the A2A server. The code in the AgentExecutor will need to create a task and provide updates to the client at regular intervals.

⚠️ If you want to skip directly to the code, check out the example on GitHub.

Let’s get into the details in the following order:

- Writing an agent that provides updates while it is doing work: I will use the OpenAI Agents SDK with its support for agent hooks

- Writing an AgentExecutor that accepts a message, creates a task and provides updates to the client

- Updating the A2A Server to support streaming

- Updating the A2A Client to support streaming

AI Agent that provides updates

Although streaming updates is an integral part of A2A, the agent that does the actual work needs to provide feedback about its progress. That work is up to you, the developer.

In my example, I use an agent created with the OpenAI Agents SDK. This SDK supports AgentHooks that execute at certain events:

- Agent started/finished

- Tool call started/finished

The agent class in agent.py on GitHub uses an asyncio queue to emit both the hook events and the agent’s reponse to the caller. The A2A AgentExecutor uses the invoke_stream() method which returns an AsyncGenerator.

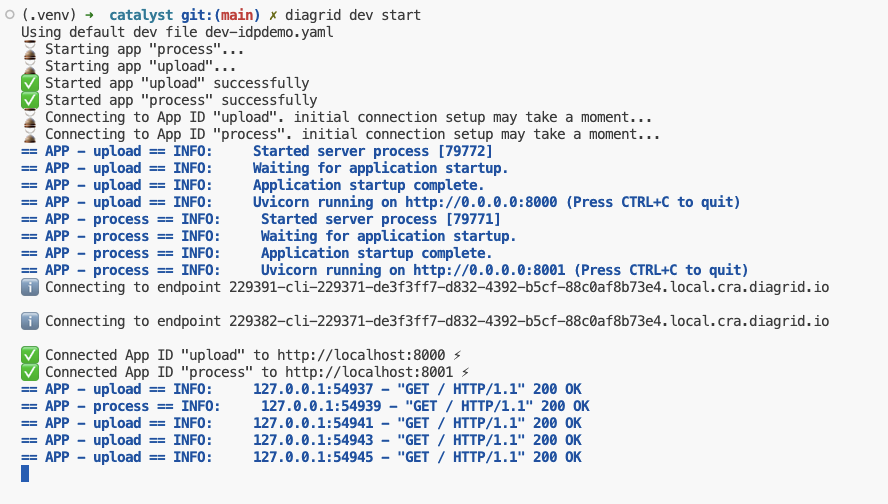

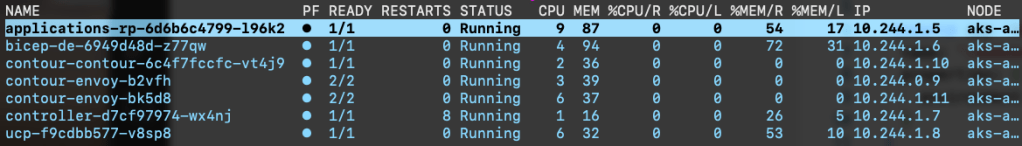

You can run python agent.py independently. This should result in the following:

The agent has a tool that returns the current date. The hooks emit the events as shown above followed by the final result.

We can now use this agent from the AgentExecutor and stream the events and final result from the agent to the A2A Client.

AgentExecutor Tasks and Streaming

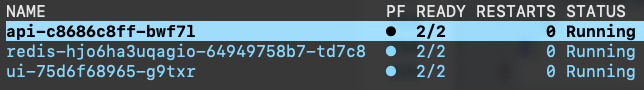

Instead of simply returning a message to the A2A client, we now need to initiate a long-running task that sends intermediate updates to the client.. Under the hood this uses SSE (Server Sent Events) between the A2A Client and A2A Server.

The file agent_executor.py on GitHub contains the code that makes this happen. Let’s step through it:

message_text = context.get_user_input() # helper method to extract the user input from the context

logger.info(f"Message text: {message_text}")

task = context.current_task

if not task:

task = new_task(context.message)

await event_queue.enqueue_event(task)

Above, we extract the user’s input from the incoming message and we check if the context already contains a task. If not, we create the task and we queue it. This informs the client a task was created and that sse can be used to obtain intermediate results.

Now that we have a task (a new or existing one), the following code is used:

updater = TaskUpdater(event_queue, task.id, task.contextId)

async for event in self.agent.invoke_stream(message_text):

if event.event_type == StreamEventType.RESPONSE:

# send the result as an artifact

await updater.add_artifact(

[Part(root=TextPart(text=event.data['response']))],

name='calculator_result',

)

await updater.complete()

else:

await updater.update_status(

TaskState.working,

new_agent_text_message(

event.data.get('message', ''),

task.contextId,

task.id,

),

)

We first create a TaskUpdater instance that has the event queue, current task Id and contextId. The task updater is used to provide status updates, complete or even cancel a task.

We then call invoke_stream(query) on our agent and grab the events it emits. If we get a event type of RESPONSE, we create an artifact with the agent response as text and mask the task as complete. In all other cases, we send a status event with updater.update_status(). A status update contains a task state (working in this case) and a message about the state. The message we send is part of the event that is emitted from invoke_stream() and includes things like agent started, tool started, etc…

So in short, to send streaming updates:

- Ensure your agents emit events of some sort

- Use those events in the

AgentExecutorand create a task that sends intermediate updates until the agent has finished

However, our work is not finished. The A2A Server needs to be updated to support streaming.

A2A Server streaming support

The A2A server code in is main.py on GitHub. To support streaming, we need to update the capabilities of the server:

capabilities = AgentCapabilities(streaming=True, pushNotifications=True)

⚠️ pushNotifications=True is not required for streaming. I include it here to show that sending a push notification to a web hook is also an option.

That’s it! The A2A Server now supports streaming. Easy! 😊

Streaming with the A2A Client

Instead of sending a message to the non-streaming endpoint, the client should now use the streaming endpoint. Here is the code to do that (check test_client.py for the full code):

message_payload = Message(

role=Role.user,

messageId=str(uuid.uuid4()),

parts=[Part(root=TextPart(text=question))],

)

streaming_request = SendStreamingMessageRequest(

id=str(uuid.uuid4()),

params=MessageSendParams(

message=message_payload,

),

)

print("Sending message")

stream_response = client.send_message_streaming(streaming_request)

To send to the streaming endpoint, the SendStreamingMessageRequest() function is your friend, together with client.send_message_streaming()

We can now grab the responses as they come in:

async for chunk in stream_response:

# Only print status updates and text responses

chunk_dict = chunk.model_dump(mode='json', exclude_none=True)

if 'result' in chunk_dict:

result = chunk_dict['result']

# Handle status updates

if result.get('kind') == 'status-update':

status = result.get('status', {})

state = status.get('state', 'unknown')

if 'message' in status:

message = status['message']

if 'parts' in message:

for part in message['parts']:

if part.get('kind') == 'text':

print(f"[{state.upper()}] {part.get('text', '')}")

else:

print(f"[{state.upper()}]")

# Handle artifact updates (contain actual responses)

elif result.get('kind') == 'artifact-update':

artifact = result.get('artifact', {})

if 'parts' in artifact:

for part in artifact['parts']:

if part.get('kind') == 'text':

print(f"[RESPONSE] {part.get('text', '')}")

# Handle initial task submission

elif result.get('kind') == 'task':

print(f"[TASK SUBMITTED] ID: {result.get('id', 'unknown')}")

# Handle final completion

elif result.get('final') is True:

print("[TASK COMPLETED]")

This code checks the the type of content coming in:

- status-update: when AgentExecutor sends a status update

- artifact-update: when AgentExecutor sends an artifact with the agent’s response

- task: when tasks are submitted and completed

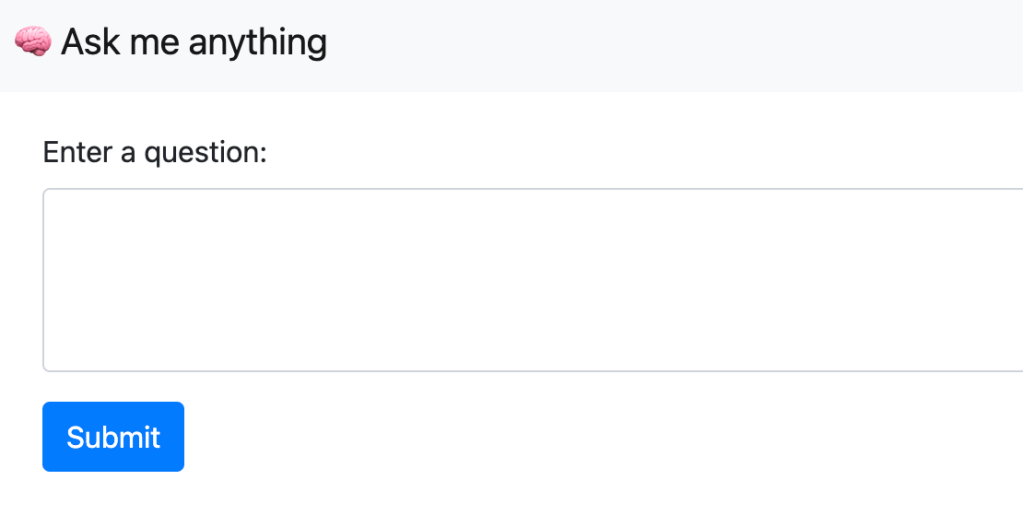

Running the client and asking what today’s date is, results in the following response:

Streaming is working as intended! But what if you use a client that does not support streaming? That actually works and results in a full response with the agent’s answer in the result field. You would also get a history field that contains the initial user question, including all the task updates.

Here’s a snippet of that result:

{

"id": "...",

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"result": {

"artifacts": [

{

"artifactId": "...",

"name": "calculator_result",

"parts": [

{

"kind": "text",

"text": "Today's date is July 13, 2025."

}

]

}

],

"contextId": "...",

"history": [

{

"role": "user",

"parts": [

{

"kind": "text",

"text": "What is today's date?"

}

]

},

{

"role": "agent",

"parts": [

{

"kind": "text",

"text": "Agent 'CalculatorAgent' is starting..."

}

]

}

],

"id": "...",

"kind": "task",

"status": {

"state": "completed"

}

}

}

Wrapping up

You have now seen how to run longer running tasks and provide updates along the way via streaming. As long as your agent code provides status updates, the AgentExecutor can create a task and provide task updates and the task result to the A2A Server which uses SSE to send them to the A2A Client.

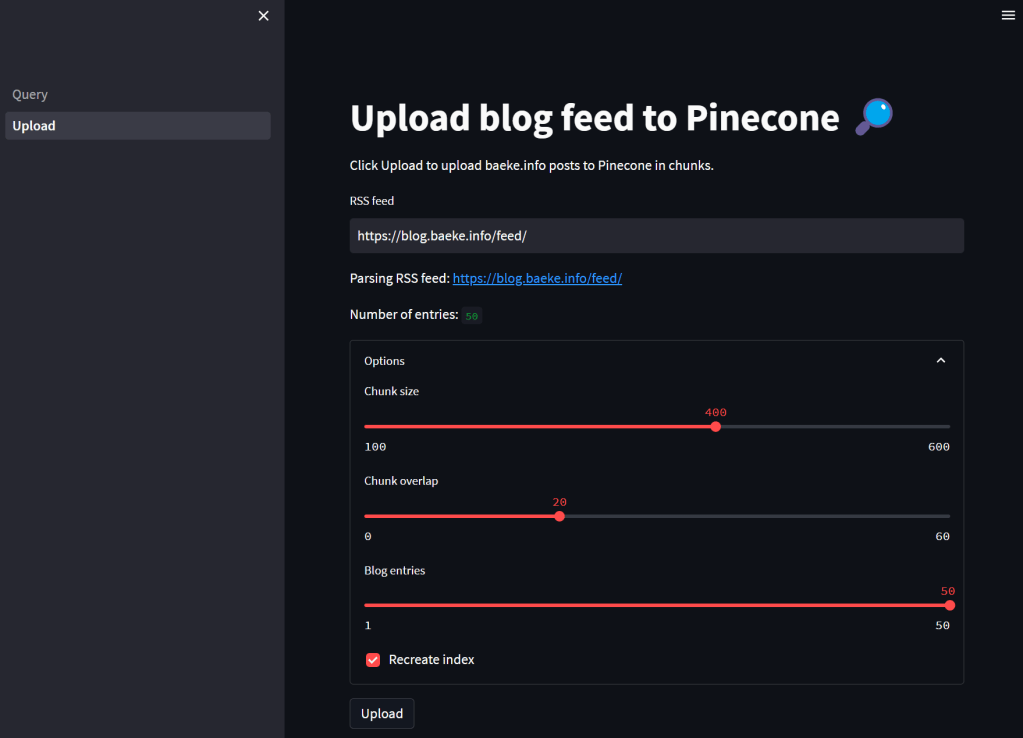

In an upcoming post, we will take a look at running a multi-agent solution in the Azure cloud.