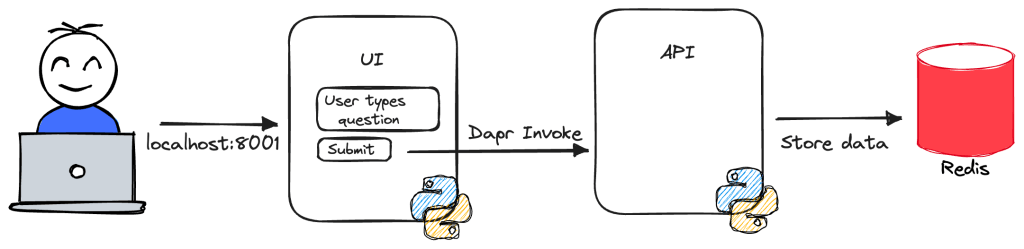

In a previous post, we looked at the basics of deploying a multi-container app that uses Dapr with Radius. In this post, we will add two things:

- a recipe that deploys Redis

- a gateway: to make the app available to the outside world

Find the full code and app.bicep in the following branch: https://github.com/gbaeke/raddemo/tree/radius-step1.

Recipes

When a developer chooses a resource they would like to use in their app, like a database or queue, that type of resource needs to be deployed somehow. In my sample app, the api saves data to Redis.

From an operator point of view, and possibly depending on the environment, Redis needs to be deployed and configured properly. For instance in dev, you could opt for Redis in a container without a password. In production, you could go for Azure Redis Cache instead with TLS and authentication.

This is where recipes come in. They deploy the needed resources and provide the proper connections to allow applications to connect. Let’s look at a recipe that deploys Redis in Kubernetes:

resource redis 'Applications.Datastores/redisCaches@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'redis'

properties: {

application: app.id

environment: environment

}

}

Note: you can get a list of recipes with rad recipe list; next to Redis, there are recipes for sqlDatabases, rabbitMQQueues and more; depending on how you initialised Radius, the recipe list might be empty

The above recipe deploys Redis as a container to the underlying Kubernetes cluster. The deployment is linked to an environment. Just like in the previous blog post, we just use the default environment. Working with environments and workspaces will be for another post.

In fact, this recipe does not specify the recipe explicitly. This means that the default recipe is used, which in this case is a Redis container in Kubernetes.

Note that the above recipe actually deploys the resource. It is quite possible that your Redis Cache is already deployed without a recipe. In that case, you can set resourceProvisioning to manual and set hostname, port and other properties manually, via secret integration or with references to another Bicep resource. For example:

resource redis 'Applications.Datastores/redisCaches@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'redis'

properties: {

environment: environment

application:app.id

resourceProvisioning: 'manual'

resources: [{

id: azureRedis.id

}]

username: 'myusername'

host: azureRedis.properties.hostName

port: azureRedis.properties.port

secrets: {

password: azureRedis.listKeys().primaryKey

}

}

}

Note: above, references are made to azureRedis, a symbolic name for a Bicep resource, implying that Azure Redis Cache is deployed from the same Bicep file but without a recipe

In either case (deployment or reference), when a connection from a container is made to this Redis resource, a number of environment variables are set inside the container. For example:

CONNECTION_CONNECTIONNAME_HOSTNAMECONNECTION_CONNECTIONNAME_PORT- …

Connecting the api to Redis

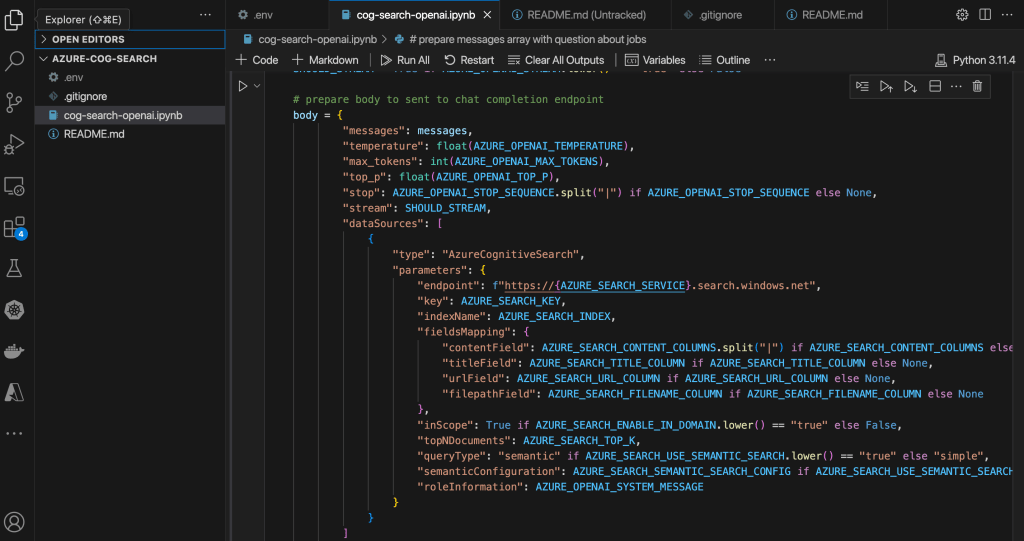

To connect the api container to Redis, we use the following app.bicep (please read the previous article for the full context):

import radius as radius

@description('Specifies the environment for resources.')

param environment string

resource app 'Applications.Core/applications@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'raddemo'

properties: {

environment: environment

}

}

resource redis 'Applications.Datastores/redisCaches@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'redis'

properties: {

application: app.id

environment: environment

}

}

resource ui 'Applications.Core/containers@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'ui'

properties: {

application: app.id

container: {

image: 'gbaeke/radius-ui:latest'

ports: {

web: {

containerPort: 8001

}

}

env: {

DAPR_APP: api.name // api name is the same as the Dapr app id here

}

}

extensions: [

{

kind: 'daprSidecar'

appId: 'ui'

}

]

}

}

resource api 'Applications.Core/containers@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'api'

properties: {

application: app.id

container: {

image: 'gbaeke/radius-api:latest'

ports: {

web: {

containerPort: 8000

}

}

env: {

REDIS_HOST: redis.properties.host

REDIS_PORT: string(redis.properties.port)

}

}

extensions: [

{

kind: 'daprSidecar'

appId: 'api'

appPort: 8000

}

]

connections: {

redis: {

source: redis.id // this creates environment variables in the container

}

}

}

}

Note the connections array in the api resource. In that array, we added redis and we reference the redis recipe’s id.

Because our api expects the Redis host and port in environment variables different from the ones provided by the connection, we set the variables the api expects ourselves and reference the Redis recipe’s properties.

The environment variables in the api container set by the connection will be CONNECTION_REDIS_HOSTNAME etc… but we do not use them here because that would require a code change.

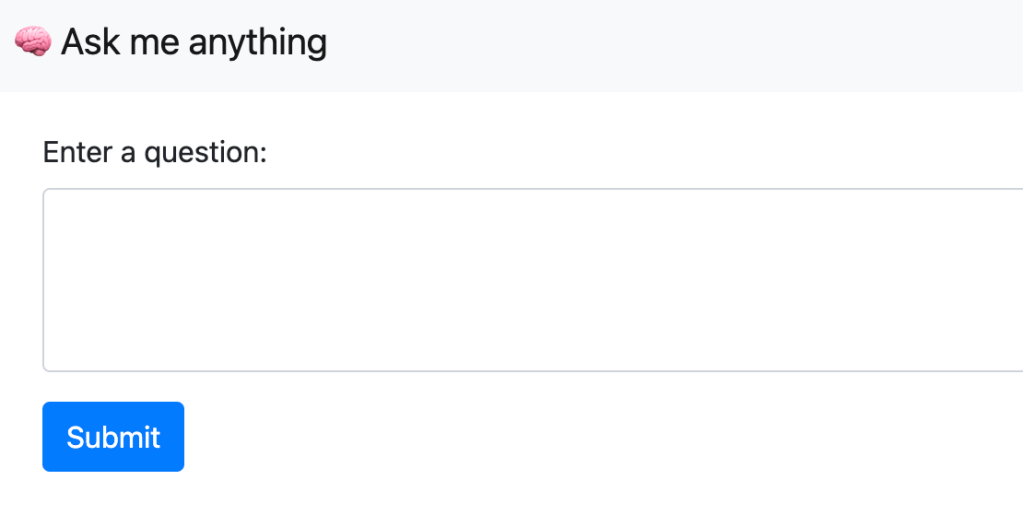

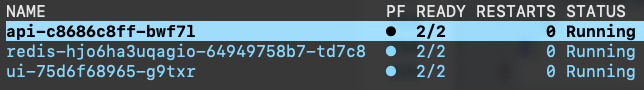

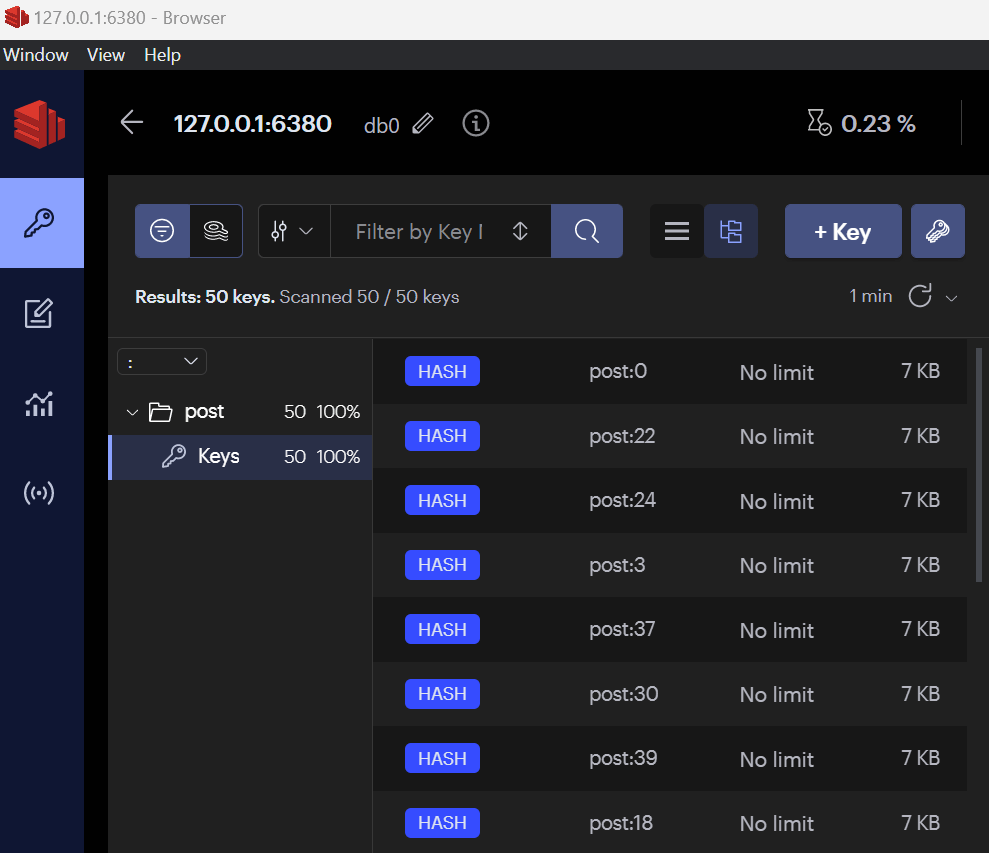

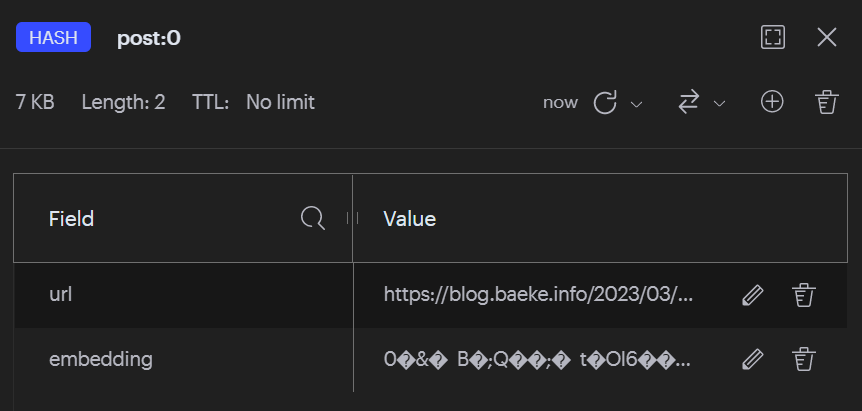

When you run this app with rad run app.bicep, Redis will be deployed. When the user submits a question via the ui, the logs will show that the Redis call succeeded:

api-c8686c8ff-bwf7l api INFO:root:Stored result for question Hello in Redis redis-hjo6ha3uqagio-64949758b7-td7c8 redis-monitor 1698071908.381740 [0 10.244.0.24:59750] "SET" "Hello" "This is a fake result for question Hello"

Because rad run streams all logs, the redis-monitor logs are also shown. They clearly state a Redis SET operation was performed.

There is much more to say about recipes. You can even create your own recipes. They are just bicep (or Terraform) modules you publish to a registry. See authoring recipes for more information.

Adding a gateway

So far, we have accessed the ui of our application via port forwarding. The ui listens on port 8001 which is mapped to http://localhost:8001 by rad run. What if we want to make the application available to the outside world?

To make the ui available to the outside world, we can add the following to app.bicep:

resource gateway 'Applications.Core/gateways@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'gateway'

properties: {

application: app.id

routes: [

{

path: '/'

destination: 'http://ui:8001'

}

]

}

}

The above adds a gateway to our app and adds one route: http://ui:8001.

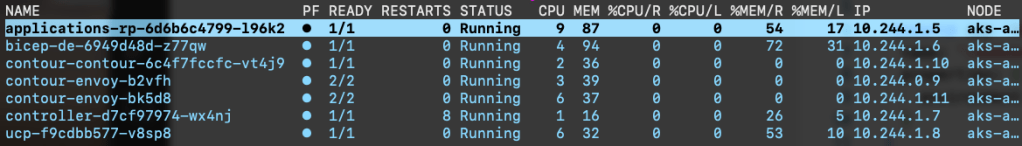

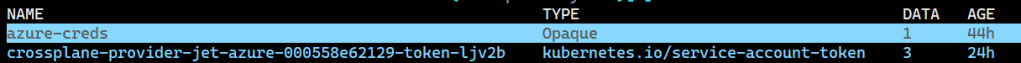

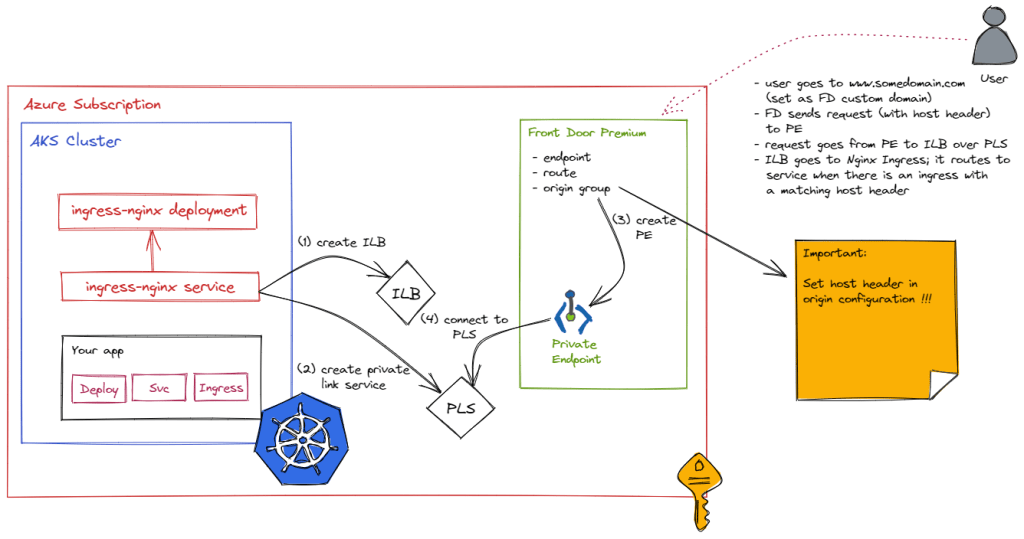

During deployment of the Radius control plane, Radius deployed Contour. Contour uses Envoy as the data plane and a service of type LoadBalancer makes the data plane available to the outside world.

In k9s, you should see the following pods in the Radius control plane namespace (radius-system):

You will also find the service of type LoadBalancer:

When you create a gateway with Radius, it creates a Kubernetes resource of kind HTTPProxy with apiVersion projectcontour.io/v1 in the same namespace as your app. The spec of the resource refers to another HTTPProxy (ui here) and sets the fqdn (fully qualified domain name) to gateway.raddemo.4.175.112.144.nip.io.

nip.io is a service that resolves a name to the IP address in that name, in this case 4.175.122.144. That IP address is the IP address used by the Azure Load Balancer.

The HTTPProxy ui defines the service and port it routes to. Here that is a service called ui and port 8001.

You can set your own fully qualified domain name if you wish, in addition to specifying a certificate to enable TLS.

The HTTPProxy resources instruct Contour to configure itself to accept traffic on the configured FQDN and forward it to the ui service.

The full Bicep code to deploy the containers, Redis and the gateway is below:

import radius as radius

@description('Specifies the environment for resources.')

param environment string

resource app 'Applications.Core/applications@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'raddemo'

properties: {

environment: environment

}

}

resource redis 'Applications.Datastores/redisCaches@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'redis'

properties: {

application: app.id

environment: environment

}

}

resource gateway 'Applications.Core/gateways@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'gateway'

properties: {

application: app.id

routes: [

{

path: '/'

destination: 'http://ui:8001'

}

]

}

}

resource ui 'Applications.Core/containers@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'ui'

properties: {

application: app.id

container: {

image: 'gbaeke/radius-ui:latest'

ports: {

web: {

containerPort: 8001

}

}

env: {

DAPR_APP: api.name // api name is the same as the Dapr app id here

}

}

extensions: [

{

kind: 'daprSidecar'

appId: 'ui'

}

]

}

}

resource api 'Applications.Core/containers@2023-10-01-preview' = {

name: 'api'

properties: {

application: app.id

container: {

image: 'gbaeke/radius-api:latest'

ports: {

web: {

containerPort: 8000

}

}

env: {

REDIS_HOST: redis.properties.host

REDIS_PORT: string(redis.properties.port)

}

}

extensions: [

{

kind: 'daprSidecar'

appId: 'api'

appPort: 8000

}

]

connections: {

redis: {

source: redis.id // this creates environment variables in the container

}

}

}

}

To see the app’s URL, use rad app status.

Note: there is a discussion ongoing to use recipes instead of a pre-installed ingress controller like Contour. With recipes, you could install the ingress solution you prefer such as nginx ingress or any other solution.

Conclusion

In this post we added a Redis database and connected the api to Redis via a connection. We did not use the environment variables that the connection creates. Instead, we provided values for the Redis host name and port to the environment variables the api expects.

To make the application available via the built-in Contour ingress, we created a gateway resource that routes to the ui service on port 8001. The gateway creates a nip.io hostname but you can set the hostname to something different as long as that name resolves to the IP address of the Contour LoadBalancer service.