Artificial Intelligence (AI) agents have garnered significant attention, with numerous posts discussing them on platforms such as LinkedIn and X/Twitter. In that sense, this post is not different. Instead of theory though, let’s look at building an agent that has a reasoning loop in a very simple way.

Although you can build an agent from scratch, I decided to use the smolagents library from Hugging Face for several reasons:

- It is very easy to use

- It uses a reasoning loop similar to ReAct: when it receives a question, it thinks about how to solve it (thought), it performs one or more actions and then observes these actions. These thought-actions-observations steps get repeated until the agent decides the answer is correct or when the maximum amount of steps is reached

- It is very easy to add tools to the agent

- There are multiple agent types to choose from, depending on your use case. A Code Agent is the agent of choice.

The reasoning loop is important here. There is no fixed path the agent will take to answer your question or reach its goal. That’s what makes it an agent versus a workflow, which has a predefined path. There is more to that but let’s focus on building the agent.

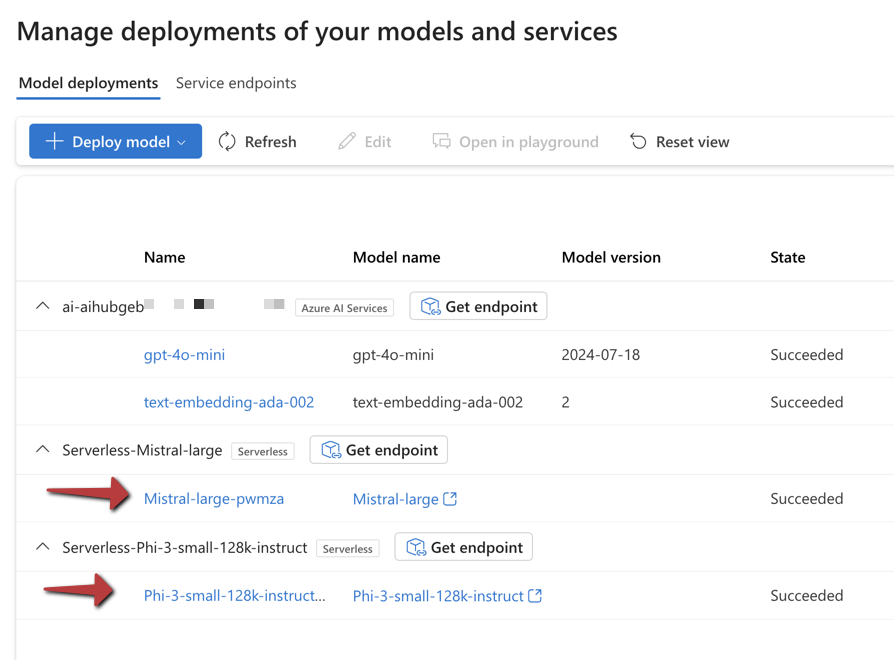

The agent uses an LLM to reason, act and observe. We will use Azure OpenAI gpt-4o in this post. I assume you have access to Azure and that you are able to deploy an Azure OpenAI services. I use an Azure OpenAI service in the Sweden Central region. To use the service, you need the following:

- The model endpoint

- The Azure OpenAI API key

Getting started

Clone the repository at https://github.com/gbaeke/smolagents_post into a folder. In that folder, create a Python virtual environment and run the following command:

pip install -r requirements.txtThis will install several packages in the virtual environement:

- smolagents: the Hugging Face library

- litellm: used to support OpenAI, Anthropic and many other LLMs in smolagents

- arize-phoenix: used to create OpenTelemetry bases traces and spans to inspect the different agent steps

Add a .env file with the following content:

AZURE_OPENAI_API_KEY=your_azure_openai_key

AZURE_API_BASE=https://your_service_name.openai.azure.com/

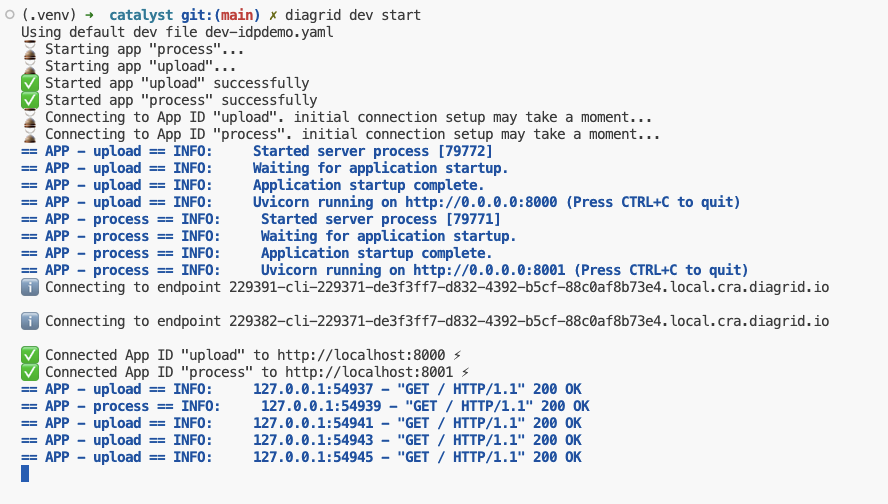

AZURE_MODEL=name_of_your_deployed_modelIn the cloned repo, there is a get_started.py. Before running it, start Phoenix Arize with python -m phoenix.server.main serve in another terminal. This gives you a UI to inspect OpenTelemetry traces at http://localhost:6006/projects. Traces will be in the default project.

Now run get_started.py as follows:

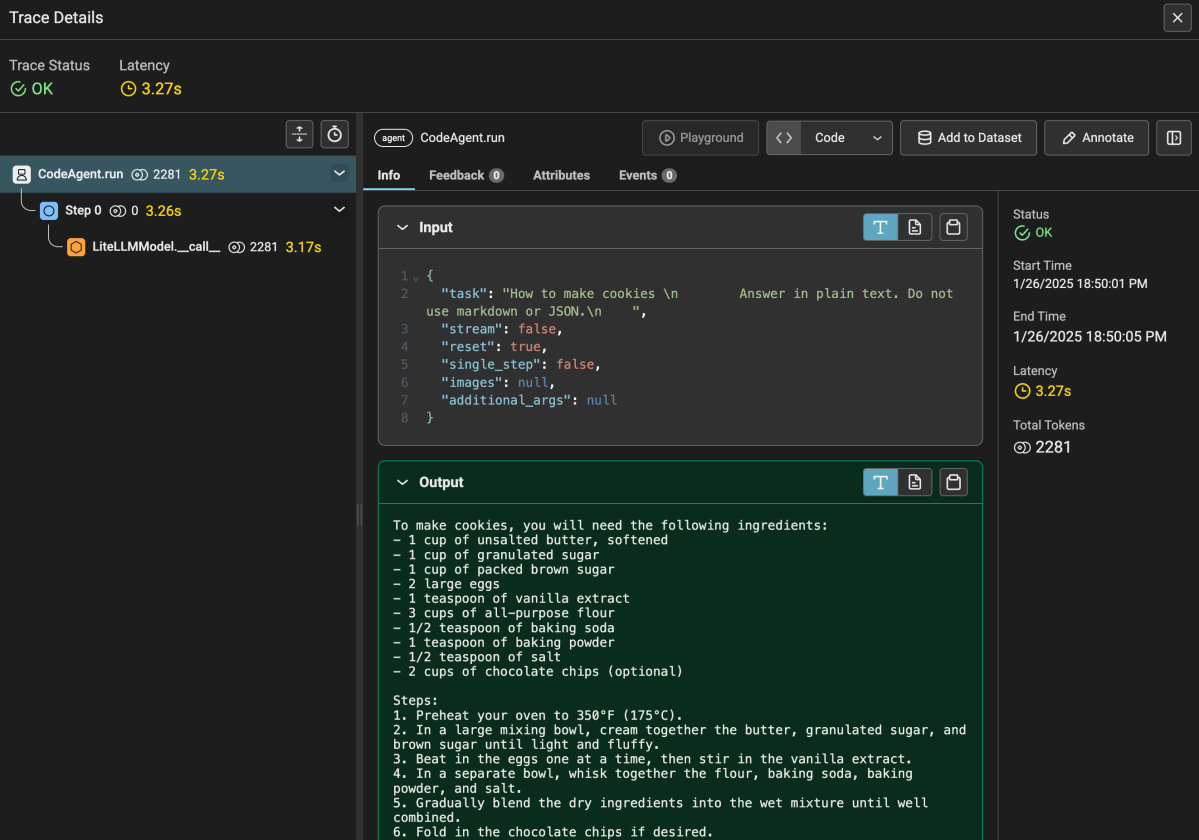

python get_started.py "How to make cookies"The result is not too exciting. But it does show that the agent works and is able to respond with the help of the Azure OpenAI model that you used. You should find a trace in Phoenix Arize as well:

Above, the agent needed only one step. It’s important to know that we use a CodeAgent here. Such an agent writes code to provide you with an answer. The code it wrote was as follows:

Thought: I will write the answer in plain text detailing the steps to make cookies.

Code:

```py

cookie_recipe = """\

To make cookies, you will need the following ingredients:

- 1 cup of unsalted butter, softened

- 1 cup of granulated sugar

- 1 cup of packed brown sugar

- 2 large eggs

- 1 teaspoon of vanilla extract

- 3 cups of all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon of baking soda

- 1 teaspoon of baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon of salt

- 2 cups of chocolate chips (optional)

Steps:

1. Preheat your oven to 350°F (175°C).

2. In a large mixing bowl, cream together the butter, granulated sugar, and brown sugar until light and fluffy.

3. Beat in the eggs one at a time, then stir in the vanilla extract.

4. In a separate bowl, whisk together the flour, baking soda, baking powder, and salt.

5. Gradually blend the dry ingredients into the wet mixture until well combined.

6. Fold in the chocolate chips if desired.

7. Drop spoonfuls of dough onto ungreased baking sheets, spacing them about 2 inches apart.

8. Bake in the preheated oven for about 10-12 minutes, or until the edges are golden brown.

9. Let the cookies cool on the baking sheets for a few minutes before transferring to wire racks to cool completely.

Enjoy your homemade cookies!

"""

final_answer(cookie_recipe)

```Of course, smolagents uses a prompt to tell the model and specifically the Code Agent how to behave. The code generates a final answer which will be the answer the user sees.

Let’s take a look at get_started.py:

from smolagents import CodeAgent, LiteLLMModel

import os

import sys

from dotenv import load_dotenv

# instrumentation

from opentelemetry import trace

from opentelemetry.sdk.trace import TracerProvider

from opentelemetry.sdk.trace.export import BatchSpanProcessor

from openinference.instrumentation.smolagents import SmolagentsInstrumentor

from opentelemetry.exporter.otlp.proto.http.trace_exporter import OTLPSpanExporter

from opentelemetry.sdk.trace.export import ConsoleSpanExporter, SimpleSpanProcessor

endpoint = "http://0.0.0.0:6006/v1/traces"

trace_provider = TracerProvider()

trace_provider.add_span_processor(SimpleSpanProcessor(OTLPSpanExporter(endpoint)))

SmolagentsInstrumentor().instrument(tracer_provider=trace_provider)

def print_usage():

print("\nUsage: python app.py \"your question in quotes\"")

print("\nExample:")

print(" python app.py \"Find the cheapest laptop\"")

print(" python app.py \"Find a Python tutorial to write a FastAPI API\"")

sys.exit(1)

def main():

# Check if a question was provided

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("\nError: Please provide a question as a command-line argument.")

print_usage()

# Get the question from command line

question = sys.argv[1]

# Load environment variables from .env file

load_dotenv()

# Check for required environment variables

if not os.getenv("AZURE_OPENAI_API_KEY"):

print("\nError: OPENAI_API_KEY not found in .env file")

sys.exit(1)

if not os.getenv("BING_SUBSCRIPTION_KEY"):

print("\nError: BING_SUBSCRIPTION_KEY not found in .env file")

sys.exit(1)

if not os.getenv("AZURE_API_BASE"):

print("\nError: AZURE_API_BASE not found in .env file")

sys.exit(1)

if not os.getenv("AZURE_MODEL"):

print("\nError: AZURE_MODEL not found in .env file")

sys.exit(1)

# get keys from .env

azure_openai_api_key = os.getenv("AZURE_OPENAI_API_KEY")

azure_api_base = os.getenv("AZURE_API_BASE")

azure_model = os.getenv("AZURE_MODEL")

# refer to Azure model as azure/NAME_OF_YOUR_DEPLOYED_MODEL

model = LiteLLMModel(model_id=f"azure/{azure_model}", api_key=azure_openai_api_key, api_base=azure_api_base, max_tokens=4096)

agent = CodeAgent(

model=model,

max_steps=10,

verbosity_level=2,

tools=[],

# additional_authorized_imports=["requests", "bs4"]

)

extra_instructions="""

Answer in plain text. Do not use markdown or JSON.

"""

result = agent.run(question + " " + extra_instructions)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Most of the code is imports, getting environment variables etc… Let’s focus on the core:

- Specifying the model the agent should use: smolagents relies on LiteLLM to give you access to many models. One of those is Azure OpenAI. To tell LiteLLM what model we use, we prefix the model name with

azure/. You can also use models directly from Hugging Face or local models. - Creating the agent: in this case we use a CodeAgent instead of a ToolCallingAgent; as you have seen above, a CodeAgent writes Python code to provide answers and executes that Python code; you will see later how it handles tools

- Doing an agent run: simply call the run method with your question; append extra instructions to your question as needed

The verbosity level ensures we can see what happens in the console:

In just a few lines of code, you have an agent that can use code to answer your questions. There is no predefined path it takes.

Try asking “What is the last post on https://atomic-temporary-16150886.wpcomstaging.com“. It will try to write code that uses Python libraries that are not allowed by default. By uncommenting the additional_authorized_imports line, the agent will probably be able to answer the question anyway:

The agent decides to use the requests and BeatifulSoup libraries to scrape this blog and retrieve the latest post. How cool is that? 😉

Adding tools

Although you can let the agent run arbitrary code, you will probably want to give the agent extra tools. Those tools might require API keys and other parameters that the Code Agent will not know how to use. They might query internal knowledge bases or databases and much, much more.

As an example, we will give the agent a Bing Search tool. It can use the tool to search for information on the web. If you enable the additional imports, it can also scrape those URLs for extra content.

Note: smolagents has a default Google Search tool that uses the Serper API.

Note: scraping will not work for dynamically loaded content; use tools such as https://firecrawl.dev or https://jina.ai with those websites; alternatively, write a tool that uses a headless browser

If you cloned the repository, you have the following:

search.py: the same code asget_started.pybut with the Bing tool included- a

toolsfolder: containsbing_search.pythat implements the tool

In search.py, you will find the following extra lines throughout the code:

from tools import bing_search # import the tool

# add the tool to a list of tools

tools = [

bing_search.BingSearchTool(api_key=bing_subscription_key)

]

# agent with tools

agent = CodeAgent(

model=model,

max_steps=10,

verbosity_level=2,

tools=tools,

additional_authorized_imports=["requests", "bs4"]

)A tool is either a Python class based on the smolagents Tool class, or a function decorated with the @tool decorator. Here, we are using a class:

- The description field in the class is used by the agent to know what the tool can do

- The inputs field describes the parameter the tool can accept

- The output fields sets the type of the output, e.g., string

The most important method of the class is the forward method. When the agent uses the tool, it executes that method. Implement the tool’s behavior in that method. The code below is the Bing tool:

from smolagents import Tool

import requests

from typing import Dict, List

class BingSearchTool(Tool):

name = "bing_search"

description = """

This tool performs a Bing web and image search and returns the top search results for a given query.

It returns a string containing formatted search results including web pages and images.

It is best for overview information or to find a url to scrape."""

inputs = {

"query": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The search query to look up on Bing",

},

"num_results": {

"type": "integer",

"description": "Number of search results to return (default: 5)",

"default": 5,

"nullable": True

},

"include_images": {

"type": "boolean",

"description": "Whether to include image results (default: False)",

"default": False,

"nullable": True

}

}

output_type = "string"

def __init__(self, api_key: str):

super().__init__()

self.api_key = api_key

self.web_endpoint = "https://api.bing.microsoft.com/v7.0/search"

self.image_endpoint = "https://api.bing.microsoft.com/v7.0/images/search"

def _get_web_results(self, query: str, num_results: int) -> List[str]:

headers = {"Ocp-Apim-Subscription-Key": self.api_key}

params = {

"q": query,

"count": num_results,

"textDecorations": False,

"textFormat": "Raw"

}

response = requests.get(self.web_endpoint, headers=headers, params=params)

response.raise_for_status()

search_results = response.json()

formatted_results = []

for item in search_results.get("webPages", {}).get("value", []):

result = f"Title: {item['name']}\nSnippet: {item['snippet']}\nURL: {item['url']}\n"

formatted_results.append(result)

return formatted_results

def _get_image_results(self, query: str, num_results: int) -> List[str]:

headers = {"Ocp-Apim-Subscription-Key": self.api_key}

params = {

"q": query,

"count": num_results,

"textDecorations": False,

"textFormat": "Raw"

}

response = requests.get(self.image_endpoint, headers=headers, params=params)

response.raise_for_status()

image_results = response.json()

formatted_results = []

for item in image_results.get("value", []):

result = f"Image Title: {item['name']}\nImage URL: {item['contentUrl']}\nThumbnail URL: {item['thumbnailUrl']}\nSource: {item['hostPageDisplayUrl']}\n"

formatted_results.append(result)

return formatted_results

def forward(self, query: str, num_results: int = 5, include_images: bool = True) -> str:

try:

results = []

# Get web results

web_results = self._get_web_results(query, num_results)

if web_results:

results.append("=== Web Results ===")

results.extend(web_results)

# Get image results if requested

if include_images:

image_results = self._get_image_results(query, num_results)

if image_results:

results.append("\n=== Image Results ===")

results.extend(image_results)

return "\n".join(results) if results else "No results found."

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

raise Exception(f"Bing search failed: {str(e)}") To try the tool, make sure you create a Bing Search resource in Azure and grab its key. Note that we are using Bing Search and not Bing Custom Search here. When you have the key, add it to the .env file:

BING_SUBSCRIPTION_KEY=your_bing_search_api_keyNow run the following command (or similar):

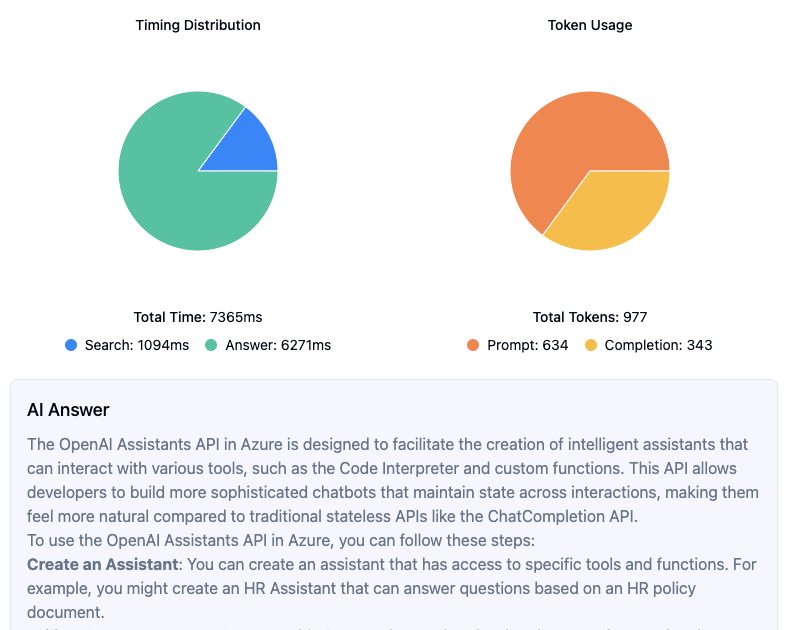

python search.py "Search the web for information about DeepSeek R1. Summarize and provide links"The agent should use multiple steps before reaching the final answer:

In step 0, the agent decides to use the BingSearchTool. It writes the following code and executes it (remember it is a CodeAgent):

results = bing_search(query="DeepSeek R1", num_results=5)

print(results)The response is a list of web and images results.

Sometimes, there are steps that do not have code to execute. Step 1 and 2 provide LLM output which the CodeAgent cannot execute. In your case, it might not happen or it might be a different number of steps. In Step 3, that is solved as the assistant output is code that uses the final_answer call to provide the final answer and stop. It basically self corrects at the expense of some extra tokens:

Thought: I will correctly format the plain text summary in the code block to ensure it handles the string properly, and then provide the final answer.

Code:

summary = """

DeepSeek R1 is an advanced AI model developed by DeepSeek-AI. It uses large-scale reinforcement learning (RL) directly on the base model without relying on supervised fine-tuning (SFT) as a preliminary step. The model has been designed to perform a variety of reasoning tasks with high accuracy and speed. DeepSeek R1 and its variants, such as DeepSeek R1-Zero and DeepSeek R1-Lite-Preview, have been launched for web, app, and API usage, competing with other leading AI models like OpenAI's Model o1.

Key Highlights:

1. DeepSeek R1 GitHub Repository: https://github.com/deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-R1

2. DeepSeek Official Website: https://www.deepseek.com/

3. DeepSeek R1 Research Paper on arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.12948

4. DeepSeek R1 API Documentation: https://api-docs.deepseek.com/news/news1120

5. Article on Nature about DeepSeek R1: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00229-6

DeepSeek R1 is positioned as a powerful AI model with significant advancements in reasoning and inference capabilities, making it a competitive alternative to other leading models in the AI community.

"""

final_answer(summary)Note: I feel those errors are a bug that might be related to the system prompt of the Code Agent.

Running code securely

Our Code Agent runs the code on the same system as the agent. For extra security, it is recommended to use secure code execution in a remote sandbox environment. To that end, smolagents supports E2B. Check the smolagents docs for more information.

E2B is similar to Azure Container Apps Dynamic Sessions. Sadly, smolagents does not support that yet.

Conclusion

We have barely scratched the surface of what is possible with smolagents. It is a small and simple library with which you can quickly build an agent that reasons, acts and observes in multiple steps until it reaches an answer. It supports a wide range of LLMs and has first-class support for Code Agents. We used the Code Agent in this post. There is another agent, the ToolCallingAgent, which uses the LLM to generate the tool calls using JSON. However, using the Code Agent is the recommended approach and is more flexible.

If you need to build applications where you want the LLM to decide on the course of actions, smolagents is an easy to use library to get started. Give it a go and try it out!